In a withering report last summer, longtime Queen Mary inspector Ed Pribonic wrote that the historic ship “has never been in worse condition” and that it soon could be “unsalvageable.” What he didn’t know was that his own job with the City of Long Beach was also becoming unsalvageable.

In a letter delivered on Christmas Eve last week, Pribonic said the city terminated an exclusive contract dating back more than 25 years to provide monthly inspections of the ship. City staffers had privately grown uneasy with the mechanical engineer’s increasingly sharp critiques of the Queen Mary’s condition–and the fallout from them.

In a brief interview, Pribonic, 72, said he’s “disappointed” that his employment with the city has come to an end but he declined further comment. Priobonic submitted his last inspection report in October. Although his monthly reports are considered public records, the city has not released any since June, despite repeated requests from the Post.

Pribonic’s firing comes as his critical reports this year made waves for the city and the ship’s operator, Urban Commons, a Los Angeles-based real estate investment and development firm.

In October, shares for a real estate investment trust sponsored by Urban Commons plummeted on the Singapore Stock Exchange in the wake of negative media reports on the Queen Mary’s inspections. In response, the company chose to temporarily halt trading as it attempted to assure wary investors that the vessel was safe and structurally sound.

Pribonic’s reports also didn’t sit well with city staffers, who said his statements went beyond professional engineering language and appeared more “emotionally driven.” Pribonic had made no secret of his growing frustration with what he considered to be Urban Commons’ recalcitrance in correcting deficiencies big and small.

Long Beach Economic Development Director John Keisler said he was particularly alarmed when Pribonic called the ship “unsalvageable.” Keisler said Pribonic, when asked to elaborate, declined to do so.

“Some of the issues he raised in his inspection reports didn’t have that detail or deeper dive, and when we asked him to provide clarification, he was unable to do that,” Keisler said.

After butting heads with Pribonic, the city in November opted for a second opinion and hired Long Beach-based engineering firm Moffatt & Nichol to review his inspection reports for best practices. The firm is also conducting its own assessment of the Queen Mary’s condition. Those reports are due early next year.

Keisler said the city plans to expand the scope of the Queen Mary inspection reports and will open the job to bids from outside engineering firms next month. He said the move to hire a new inspector is part of the city’s commitment to maintaining the ship.

“The broad takeaway is that we can do better,” he said.

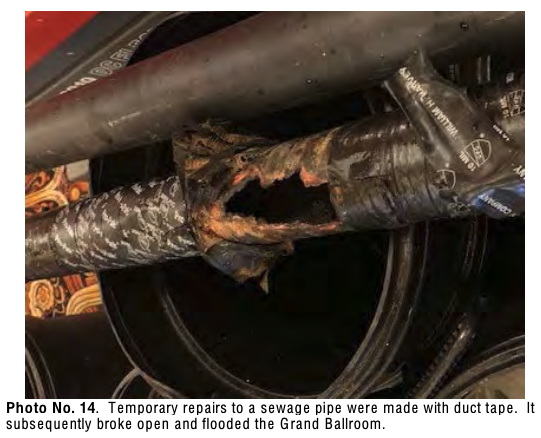

Pribonic is a former safety engineer for Disneyland who has specialized in amusement park inspections. He has worked as a consultant for the city of Long Beach since 1992 and says he has typically used strong, direct language in the nearly 400 inspection reports he has submitted on the Queen Mary. Pribonic has said that he’s tried to raise awareness over the ship’s poor condition and that the photos he includes in his reports speak for themselves.

Pribonic hasn’t been the only one to raise concerns.

A city-commissioned marine survey in 2015 projected costs of up to $289 million for urgent repairs to the ship over the next several years. Under an agreement with Urban Commons, which signed a 66-year lease to operate the city-owned ship in 2016, the city issued $23 million in bonds to fix some of the most critical repairs listed in the marine survey.

But many of the initial repairs went significantly over budget and the $23 million was spent before other critical projects could be addressed. Fire safety repairs, for example, were initially projected to cost $200,000, but the cost ballooned to $5.29 million to fix an outdated sprinkler system that apparently hadn’t been touched in decades.

Urban Commons is on the hook to fund the remaining repairs. In October, the city sent the company a letter noting that it could be in danger of defaulting on its lease agreement if it did not provide an updated plan for several repairs.

Urban Commons has since provided an updated repair plan, with projects next year, including replacing the ship’s deteriorating lifeboats.

“Working with an international treasure, such as the Queen Mary, takes considerably more thought and time than working with a modern building—for example, when replacing the lifeboats on the ship we will carefully remove each one and will replace them with exact replicas to maintain the ship’s historic integrity,” Mark Frances, the company’s managing director at the ship, said in a statement.

The operator has faced other financial struggles. An audit report from last year showed that the limited liability corporation that runs the Queen Mary, Urban Commons Queensway, suffered net losses of more than $6 million on operating costs and interest payments.

Urban Commons Principal Taylor Woods has said the company is financially stable and expected to generate significantly more revenue next year with new events and attractions.

“We are confident in the financial well-being of Urban Commons Queensway, LLC, and its ability to perform under the terms of the lease agreement with the City of Long Beach,” he said in a statement. “Since taking over the lease of the Queen Mary in 2016, our Historic Preservation program plus the Queen Mary’s Base Management and Replacement Plan has facilitated nearly $29 million in improvements—far more than any previous owner.”

Urban Commons wouldn’t be the first operator to struggle making money with the ship.

Over the decades, a series of companies has failed to make the ship and surrounding area profitable.

The Diners Club Credit Card Co., which had the first lease to run the Queen Mary, invested $5.6 million in improvements, but it backed out of the project in 1970 before the ship opened to the public. The Walt Disney Co. later owned the ship but quit its lease shortly after the release of a 1992 marine survey that identified $27 million needed for repairs.

Joe Prevratil, who signed a lease to run the ship in 1993, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2006 when the city demanded several million dollars in unpaid rent. Prevratil in 2007 agreed to pay the city $4.9 million in a bankruptcy settlement. Save the Queen LLC purchased the lease through an auction at bankruptcy and then defaulted on its loan in 2009.

Mary Rohrer, a longtime advocate for the ship, said the Queen Mary has suffered under a string of inconsistent operators.

Rohrer is now working as the community outreach coordinator for the nonprofit QMI Restore the Queen, which plans to raise money to help fund repairs.

Rohrer has been reading Pribonic’s reports since 2012. She said Pribonic has done a great service to the Queen Mary over the decades.

“These reports have been sitting on the shelves for years with nobody in the city looking at them or paying attention,” she said. “But I’m glad at least they’re paying attention now. We just want what’s best for the ship.”