When the principal of Holy Innocents School arrived on campus Monday morning, she noticed something strange. The door leading to the hall where children attend mass each day was ajar, so she sent her son to look inside.

“‘Mommy, it’s trashed,’” Principal Cyril Cruz remembered him saying when he returned. Cruz ran to look inside for herself and discovered that the assembly hall, chapel and classrooms had been broken into and vandalized.

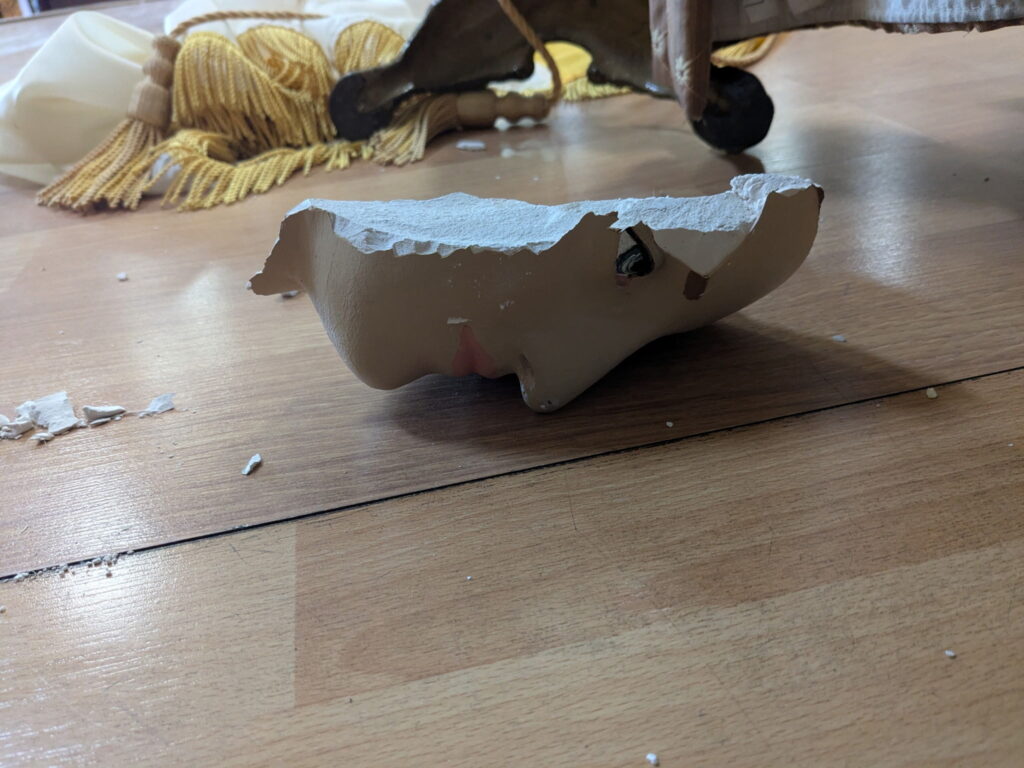

Statues of the Virgin Mary were smashed — hands and at least one head chopped off. Prayer books were dumped from bookshelves and strewn across the floor. The tabernacle had been ripped from its chapel, its doors pried partially open. Snack boxes, raided. Guitars and musical instruments, damaged. Curtains pulled down, cabinets torn from the walls. Audiovisual equipment was pillaged from closets and stacked on carts. The internet had been cut. Tiny peg dolls, used for teaching the youngest students, ransacked.

“This is like my home,” Cruz said, adding that she felt unsettled and violated. Above all, she expressed disbelief that someone would do this to the 300 children in grades TK-12 who attend the parochial school in Southeast Wrigley.

School staff called Long Beach police around 7 a.m., according to Tony Tripp, director of advancement. About four hours later, they arrived on the scene — and once they saw the damage, Tripp said officers expressed alarm at its extent.

Little is known about the perpetrators. Long Beach police said it appeared to have been a “crime of opportunity with damage caused during the course of the burglary.” Tripp suspects more than one person participated because soda bottles had been opened, spilled and tracked across the floor — by multiple shoeprints, he said. The police forensics team arrived soon after to look for evidence, Tripp and Cruz said.

The head of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division said on social media that her office, too, would launch an investigation into the crime. Long Beach police said Tuesday they had not yet been contacted about any federal probe.

Tripp was unable to discern what had been stolen due to the disarray and active crime scene. But he was beginning to inventory the cost of the damage, which he called “definitely a high amount.” One statue of the Blessed Mother, which has been in the school since 1958, was worth at least $40,000, he said. Another statue in the atrium was valued around $10,000. Many of the religious articles couldn’t be priced, as they had been handmade by the sisters, Tripp said.

Cruz canceled mass, normally held in the assembly hall, but she kept the school open. Around noon, the students gathered for a rosary procession on the campus, avoiding the barricade tape around the crime scene. The sisters encouraged students to pray for the “tragedy that’s happened” and for “the people who did it” — that they reflect on their actions and “either turn themselves in or stop their life of crime,” Tripp said.

High-ranking clergy and officials, including the regional bishop, archdiocese officials and representatives from the Department of Catholic Schools, visited the site in the morning and were in agreement: “They said, ‘We’ve never seen anything like this,’” Tripp said.

Marianne Dyogi, who has four children in the school and one recently graduated, sat with other parents in the courtyard and looked at photos of the damage, which she called heartbreaking — especially because the space where children learn the foundation of their faith had been destroyed. She said friends across Los Angeles and Orange counties have reached out in support.

“That Mrs. Cruz still wanted everyone here today is really important, because no one was sent home in confusion,” Dyogi said. “I’m grateful for how she leads.”