The Long Beach City Council passed a series of reforms on Tuesday that will prohibit federal agents on non-public city grounds, create a certificate program for businesses offering safe spaces to undocumented residents, and establish penalties for city workers or contractors who do not comply with its sanctuary policies.

Long Beach has never formally declared itself a “sanctuary city” — a term that has no defined legal meaning — but, since 2018, it has continued to expand its rules around non-cooperation with civil immigration enforcement, a common theme in sanctuary policies.

Tuesday’s vote was the second expansion this year of its ordinance, titled the Long Beach Values Act, and comes as high-profile immigration sweeps have continued across the Los Angeles region, where officials with the Department of Homeland Security say they have arrested more than 4,000 people since beginning their mass deportation operation on June 6.

Long Beach’s policy already banned most cooperation and data sharing between city departments and federal immigration enforcement, including a prohibition on honoring most detainer requests from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which will often ask local jurisdictions to hold inmates for extra time so agents can retrieve them for deportation. Now that non-coordination will be even more visible.

‘No Entry’ signs will soon be posted on doors and entryways in city buildings or properties that aren’t open to the public — a move meant to stop federal agents from entering without a judicial warrant. In the event authorities show up, employees will also be trained to ask for court papers.

City staff will be required to learn the new policies through pre-recorded modules online, as well as during upcoming town halls later this month. Those who don’t follow the rules could be subject to “warnings, suspensions, demotions or dismissals.”

“If there is a policy where somebody willingly, maliciously disobeys it, people get fired in the city for that,” City Manager Tom Modica said. “That’s not acceptable, doesn’t matter what the policy is.”

Residents will be allowed to report violations in an online portal, maintained by the city’s Human Resources Department.

Changes also extend to vendors, including those contracted with the city or hoping to bid on a project.

The city already prohibits employees and third-party workers from sharing data with federal authorities, but the prohibition hasn’t always been followed: The city police department mistakenly shared license plate data with ICE in 2020.

This change goes much further, allowing Long Beach to end contracts with vendors that don’t follow the Values Act, without any legal repercussions. It can also be grounds to disqualify applicants from bidding on a project.

Any data shared with a vendor must be either returned or destroyed — it’s at the city’s discretion — within 10 days.

However, City Attorney Dawn McIntosh clarified that the city cannot dictate terms in all cases, including on some major contracts, such as with cybersecurity firms, multi-national corporations like Microsoft or with specialized goods or services. Going forward, her office will also work to obtain public records on federal enforcement and pursue “legal remedies for damages to city property, programs or revenues.”

Lastly, the new policy establishes a “Safe Place” certificate for businesses that complete “Know Your Rights” training with locally accredited nonprofits.

The changes represent “a massive undertaking” for city employees, said Modica, at a scope workers have “never really experienced before.”

“It’s not something that we have had to deal with in the past,” Modica said. “The potential for masked agents with weapons to show up at your workplace asking to detain people.”

Proponents of the changes say the policies will further engender trust with people in migrant communities, allowing them to feel comfortable cooperating with local authorities, and extend beyond a performance to score political points.

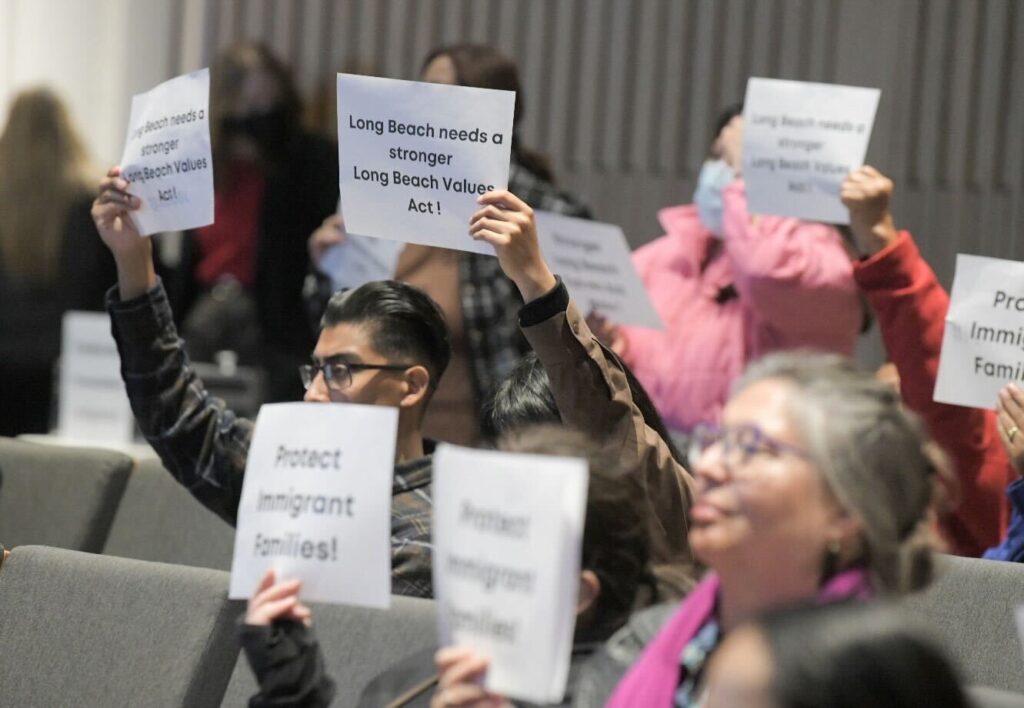

But supporters of immigrants’ rights present Tuesday night had mixed feelings about the latest amendment.

Several took note that this version dropped two requests made by civil rights groups in a Dec. 9 letter, including the removal of exceptions that allow some cooperation with immigration agents when the deportee has a serious or violent criminal history as well as the ability for individuals or groups to sue the city in the event it does not uphold the sanctuary ordinance.

Maribel Cruz, associate director of local immigrant rights group ÓRALE, asked the city to remove the loophole and to restore a private right to legal action. “The Long Beach Values Act is a powerful policy that can truly provide concrete protections but the policy as it stands is not enough,” Cruz said.

In an Aug. 8 memo by the city manager’s office, Modica explained that state law would require the city to defend employees sued for potentially violating the Values Act, a costly path that could “cripple city processes.” It would also create a “disparity” in how the city already handles allegations of employee misconduct and may conflict with employee or union agreements.

Nick Masero, a deputy city attorney, said removal of the exception for assisting ICE with deportees convicted of certain felonies could leave Long Beach open to “legal challenges and judicial scrutiny, which it might not survive.”

Establishing a private right of action, he added, would waive several legal immunities enjoyed by the city and result in “new, expensive and meritless litigation.”

With the backdrop of criticisms by local civil rights groups that the policy package continues to allow some loopholes and lacks public accountability tools, Mayor Rex Richardson reminded the room that the city never asked to be put into this situation.

Looking back at a turbulent few months, he recounted “increased enforcement activities,” “masked individuals” and “unmarked vehicles” that have sown “fear and terror” into residents. He stressed that existing city policy must keep pace with the ever-advancing tactics used by federal immigration authorities.

As part of a $3.7 billion spending plan unveiled last month, Richardson suggested the city reserve $5 million for assistance and legal defense for those facing the specter of deportation or federal cuts that could put more people on the streets.

He also recommends establishing a new legal reserve for the city attorney’s office to defend against legal challenges the Trump Administration may bring against Long Beach directly.

“We need to continue to place a focus on why we’re in this situation is because of the federal government,” Richardson said. “… This is a situation that was brought upon us, not something that we welcome.”