Our ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings, places and things that have either been demolished, are set to be demolished, or are in motion to possibly be demolished—or were never even in existence. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural and spatial history. To keep up with previous postings, click here.

****

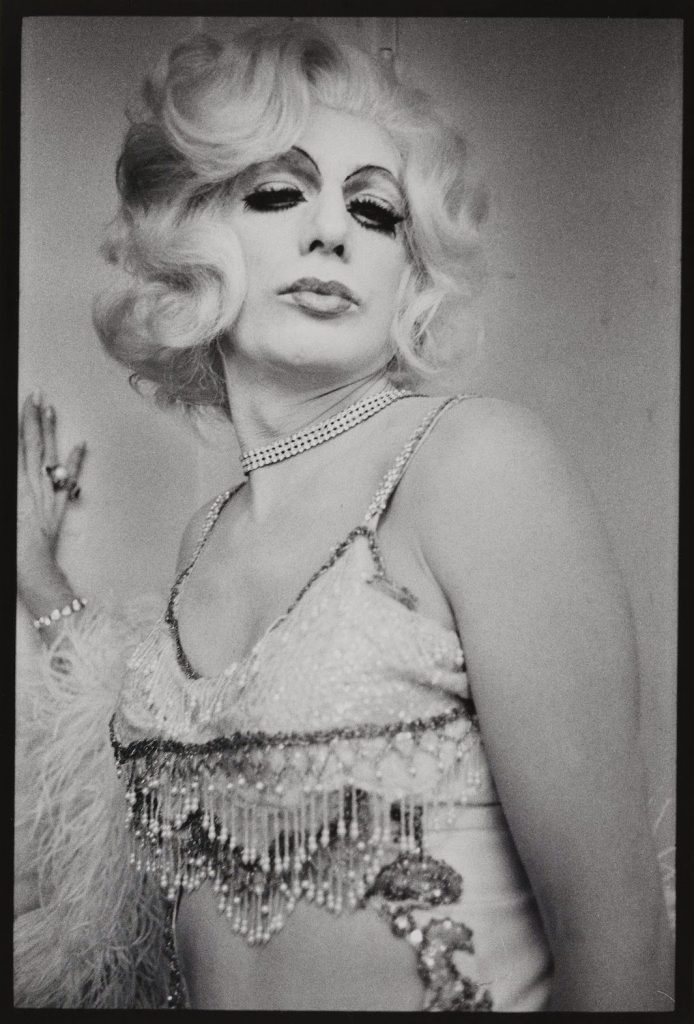

Author’s note: No existing images of Club Sylvia were able to be found by the time of this publication. We have chosen to include vintage photos from the 1971 Drag Queen Ball in Long Beach as a visual though they are not directly connected to Club Sylvia.

It was originally called Impact, nestled at the corner of 61st Street and Cherry Avenue in North Long Beach. It also acted as, at least according to Empress Boom Boom of the Long Beach Imperial Court, the headquarters for drag queens—and for good reason.

“Things were different back then,” Boom Boom, whose legal name is Frank Rubio, explained. “If you were a drag queen like myself, of course you didn’t have a legitimate ID or a picture that verified you were Frank Rubio In Drag. And there were just a lotta bars that frowned upon you—even gay ones. Unless it was Halloween, of course.”

Impact was an all-night, 3,000-square-foot mecca of sorts, located at 6101 Cherry Ave. It stayed open 24 hours on the weekend to cater to the dancers and drags who never wanted the a.m. to halt. People knew people and the bar had had an unrestricted license for years.

In 1985, allies Robert and Sylvia Oliver—who already owned a downtown bar—purchased Impact and changed it to Club Sylvia without remotely altering its purpose as a drag center. In fact, they catered to it and improved the space inside as well as installing additional lighting in its parking lot.

“We started going to Sylvia because we began slowly gathering friends who were into drag,” said longtime Long Beach resident (now residing in Palm Springs) Rick McGilton-McGlamery, speaking on behalf of his partner David. “And there just weren’t many places for them to go. The boys had their boys’ bars and the girls had their girls’ bars—there was no mixing,” he continued, echoing Rubio’s previous sentiment.

The next 15 months—from January of 1985 to the spring of 1986—would become one of the oddest and most controversial City Council battles over a space designed for entertainment. Led by then-9th District Councilmember Warren Harwood and a nearby homeowner and nurse Carol McDonald, a yearlong campaign to stifle Club Sylvia brought about accusations of homophobia, threats to recall Harwood, the misuse of city powers, and a lawsuit that would stretch into the 1990s.

Harwood initially brought the idea of rejecting the Olivers from obtaining an unrestricted entertainment license on claims that the venue was simply too loud and created parking problems, not due to the fact that Sylvia catered to gay patrons. Despite city departments offering their recommendation of an unlimited license, Harwood came armed with letters and a couple hundred signatures, leading the battle against Club Sylvia.

“The only issue is whether 2 a.m. seven nights a week is tolerable,” Harwood told the Council. “I say it’s not, and the people say it’s not… Just starting a car at 2 a.m. can wake up a child—it doesn’t matter who starts it.”

And he won. Their first unanimous vote against renewing the license—5-0 in 1985—would follow with three more votes: one a week later to re-hear the issue, another with a slim majority, 5-4, to reject the license approval yet again, followed by the granting of a limited, two-nights-a-week license. Then things shifted entirely: As Long Beach’s Pride celebration began to rise in popularity and gay rights were surfacing as a public, political issue, minds seemed to alter as well, particularly at the final meeting regarding Sylvia on May 13 of 1986.

McDonald was the most directly outspoken citizen and her Council appearance on that day sparked a fury of controversy not only when she told the Los Angeles Times that people “putting on their wigs and clicking their high heels” is not what she “likes [for] my children,” but when she proclaimed that Club Sylvia wasn’t a neighborhood bar.

Her proof? When she saw men in women’s attire on April 30 of that year—what later proved to be a benefit for AIDS nonprofit Project Ahead—she said she knew police checked their license plates and discovered many patrons were from the L.A. basin and not Long Beach directly.

When Councilmember Edgerton began questioning how she obtained such information, accusations fell onto Harwood, who insisted that he had no involvement in getting the LBPD to check the plates of Sylvia’s patrons.

In a 6-3 vote, Sylvia was finally granted a license to allow dancing seven nights a week until 2 a.m. Edgerton even admitted later that he regretted his initial decision to deny the club the license, stating he was attempting to support then-Mayor Ernie Kell, whose leaning was often toward the right.

The Sylvia saga by no means had ended.

In July of 1986, just three months after getting their license, the Olivers filed a $500,000 lawsuit against Harwood, the LBPD, and McDonald alleging that they ultimately conspired to damage their business to the point of dissolution. The Olivers even contended that Harwood told residents that the bar would bring AIDS into the neighborhood—and this led them to have to sell the club to Filiberto and Rita Magallanes in 1987.

During the five years before the two-and-a-half-week trial, the city and McDonald were dropped and damages sought—about $200,000 by that point—were directed solely at Harwood. Ultimately, a Superior Court jury ruled against the Olivers and sided with then-Assistant City Attorney Robert Shannon’s argument that bad business decisions brought Sylvia down—not Harwood’s conduct.

Though claims of a repeal were stated, nothing further came of the Sylvia saga directly. Perhaps the space was simply plagued, as Rubio put it, after Impact went away—and given that it took almost a year for the Magallanes to obtain an entertainment license as well, perhaps the wisdom of Boom Boom remains true.

Brian Addison is a columnist and editor for the Long Beach Post. Reach him at [email protected] or on social media at Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.