The mangled bicycle lies in the street while emergency responders tend to an injured cyclist. Photo: Asia Morris

Most days in the newsroom are pretty ordinary. Between the clacking of keyboard strokes, the ringing of the office phone and the gallons of coffee, there are few things that get the blood pumping more than the words “free pizza.”

It’s very seldom that a story falls into your lap or has the decency to deliver itself to your office door but that’s precisely what happened October 3 when the clatter of the newsroom was interrupted by the receptionist running in with an urgent message: a cyclist had just been hit outside and there were fears they may be dead.

The mangled bike lying near the crosswalk at the intersection of Ocean and Magnolia surely suggested it might be a miracle if anyone had survived that collision. And it seemed like with every foot between that bike and its rider’s body—a consensus of about 100-plus feet, according to this office poll—the likelihood of the outcome being positive was slim.

The cyclist survived his near-death experience, and in a morbid turn of luck, his being at the wrong place at the right time reminded me to dig into a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request regarding the number of cyclists and pedestrians involved in accidents this year that had been received while I was out on vacation. That day was my first day back.

If you’ve felt that there has been an increase in the number of people being injured or killed by vehicles this year, it’s not just a feeling. While accidents involving cyclists or pedestrians with vehicles have historically fluctuated, the recent trend has continued upward with the more troubling factor being that more people are dying.

According to data collected by the Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) over the last decade, there have been no less than 444 of these types of accidents per year resulting in an injury or death of a cyclist or a pedestrian. That low was taken from the first year of data (2006) and the high over that 10-year period was experienced in 2012 when 627 such accidents occurred.

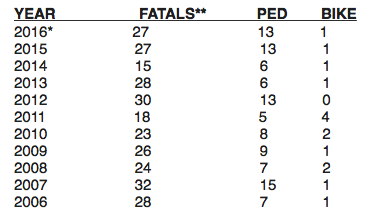

Over the same period of time, the lowest death total per year for cyclists and pedestrians stands at seven. That total was seen in both 2013 and 2014 but has at least doubled over the last two years with 14 in 2015 and 14 reported incidents through November 30 this year.

According to Post records, to date, no other cyclists or pedestrians have been killed this year since then. Cyclists fared a lot better in terms of surviving accidents accounting for only a handful of deaths over the past decade, with just one recorded for each of the last two years.

Those numbers were adjusted from the original count provided in the FOIA, with the explanation that some incidents are reclassified for instances of suicide or deaths being attributed to an accident that occurred the previous year.

They do not include deaths recorded by the California Highway Patrol (CHP). The FOIA put the 2015 and 2016 totals both above 17.

They do not include deaths recorded by the California Highway Patrol (CHP). The FOIA put the 2015 and 2016 totals both above 17.

Lieutenant Kris Klein, who heads the traffic section for the LBPD, acknowledged the spike in deaths in the city and said there are certainly problem areas in the city’s network of streets where accidents are more prevalent. He singled out the Traffic Circle and the triple-intersection at Los Coyotes Diagonal/Clark/Stearns as places where there are frequent issues.

Klein said it’s difficult to pinpoint what exactly is accounting for the recent rise in fatal accidents as they happen more sporadically in the city and give the department little to work off of in terms of patterns. He did say though, that the recent injection of technology into cars and people’s pockets does have a role to play.

“Especially over the past few years, we’re seeing a lot more distraction both on the pedestrian and the driver side,” Klein said. “You’ve seen over the past few years cell phones have gotten more advanced. There’s more to distract you while you’re walking, well that also exists in the vehicles as well.”

Not to place all the blame on technology, Klein said the fundamental idea of being defensive in whichever medium of transportation you’re using could help with prevention. The department gets grant money for education programs and he said that re-education process needs to extend to everyone on the road, pedestrians included.

Walking defensively is just as important as driving defensively, he said, stressing the importance for walkers to make sure that drivers see them before they enter the street. Even if you’re in the right, you don’t want to be explaining that with a broken leg.

“It doesn’t matter who’s right when you get injured,” Klein said. “It’s great if you’re right and it wasn’t your fault but you’re the one in the hospital or worse and it doesn’t help anybody.”

Long Beach is not alone in seeing increases in these types of accidents. Its yearly totals pale in comparison to New York City, which had 18 pedestrians die in traffic accidents in February of this year alone. As of November, Denver had already surpassed its 2015 total with 22 pedestrians or cyclists perishing this year. In 2013, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reported that over 4,700 pedestrians had been killed in traffic crashes in the United States, or one person every two hours.

A study published in the Los Angeles Times earlier this year showed that pedestrian deaths in California had risen 7 percent statewide in the first half of 2015. This is not a regional trend, but the nature of urban settings and mixing machines, large numbers of people and decision making is having an impact.

Herbie Huff, a research associate at UCLA’s Lewis Center and Institute of Transportation Studies, was part of team that released a report this August, which analyzed cyclist safety in Los Angeles County. It found that the county outpaced the statewide average of accidents by nearly a full percentage point, accounting for nearly one-third of the total collisions in California from 2004-2013.

Huff said that while the national rate has been trending up, cyclist deaths are like the “shark attack” of traffic safety incidents. She conceded that they do represent a concerning and disproportionate total of traffic fatalities but said that’s precisely what makes them so difficult to study and understand. There are so few and they almost always involve different circumstances.

One variable that stuck out was the width of streets, which the group’s work showed had an impact on the rate of accidents. Huff explained that wider streets tend to have more vehicles, bigger vehicles and both are moving at a greater speed, which escalates the likelihood of an accident happening and that accident causing injury or death.

“In traffic safety literature, in general, the big variable that jumps out is speed,” Huff said. “When you look at traffic safety campaigns, most of them are focused on speed because speed is the variable that determines whether you’re going to get injured or seriously injured or die.”

She said that bike highways, lanes or other forms of infrastructure are good things, something supported by the report’s findings. While the number of incidents did appear to be larger on bike-dedicated portions of the county, those stretches also saw a marked uptick in ridership. The key, Huff said, is to make sure those on the street are aware of how to safely operate their bikes.

“As a daily rider who occasionally rides with people with less experience I, over and over again, observe how I’m able to defensively ride in a way that I avoid situations that could cause a crash,” Huff said. “I’ve ridden with other people that aren’t aware that something they just did was really dangerous.”

The city has certainly taken steps to try and improve safety for all users of the road, including a 2015 decision to close down the triple-intersection at 7th-Martin Luther King Boulevard-Alamitos with the creation of Gumbiner Park and more recently the city’s decision to put a portion of East Ocean on a “road diet” to slow speeds near Belmont Shore.

Several other public works initiatives have secured protected bike lanes in east and north Long Beach, placing physical barriers between cyclists and vehicles. And just last week the city was awarded a $4.5 million grant from the Caltrans Highway Safety Improvement Program that will help fund projects to improve pedestrian crossings and install new traffic signals at selected points in the city, including the Traffic Circle.

With the city deep into the holiday season and people rushing from engagement to engagement the chance for an accident could arguably be at one of its highest points during any year. Klein’s simple plea for motorists, pedestrians and cyclists to pay attention to the road and their surroundings could go a long way toward ensuring everyone makes it to the New Year.

“Every collision is preventable one way or the other,” Klein said. “Somebody did something wrong and that’s how the collision happened. I think if we got back to the basics of walking and driving defensively and following all the rules of the road we would significantly reduce these collisions.”