Deadly fires in Long Beach have skyrocketed over the past year, with 10 people dying in blazes in 2023 compared to an average of one or two fire deaths in the previous few years.

In his 29 years with the Long Beach Fire Department, Deputy Fire Chief Robbie Grego said, “I can’t recall seeing this many deaths.”

Reasons for the surge of deadly fires are unclear, and no common thread is apparent in the incidents. In five of the six fires with fatalities this year, the cause was “undetermined”; the sixth — a boat fire in Alamitos Bay — was deemed “unintentional,” according to fire department reports.

One death was in February, when a victim was discovered during a blaze on the second floor of a board and care home in Cambodia Town.

Two more deadly fires occurred in March. One was in a home with its attic converted to living space; two people died. The other took place in a Belmont Shore apartment, where firefighters entered a building with smoke coming from the second floor and found a man slumped against the wall. He died later at St. Mary Medical Center of fire-related injuries.

In April, an abandoned Downtown building where unhoused people had been sheltering caught fire. Firefighters escorted out one person who ran away without medical treatment; inside the building, they found a man who was later declared dead, according to fire department records.

A May fire in an abandoned auto shop on Long Beach Boulevard near Poly High School caused three deaths. And in an August incident, a boat refueling in Alamitos Bay burst into flames, killing two people.

Fire officials say the wave of deaths is part of an overall increase in fires across the city since 2016.

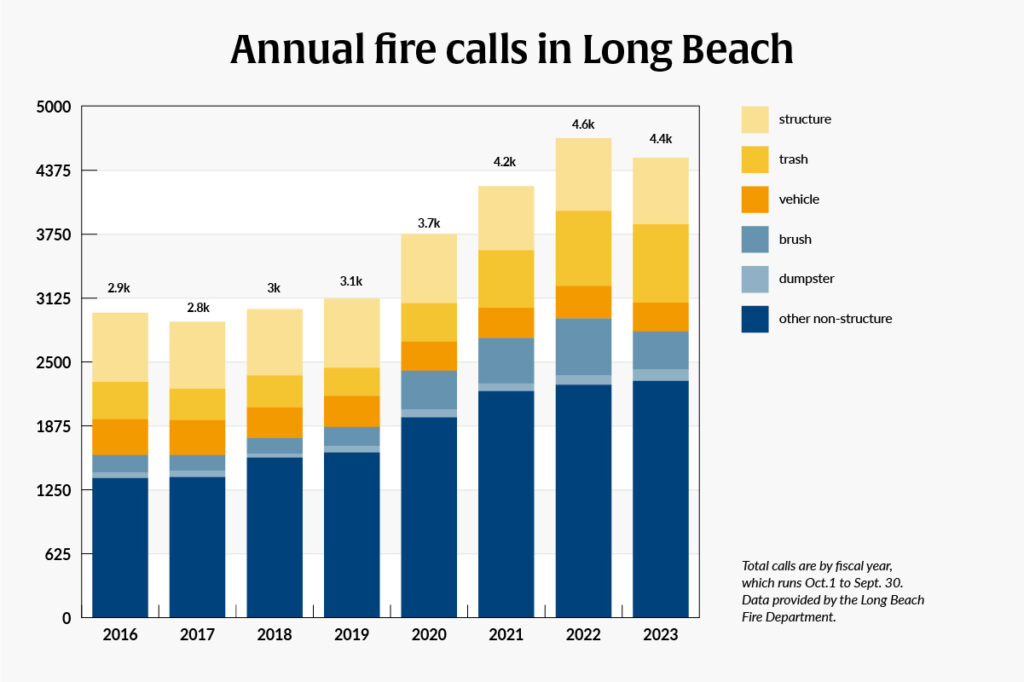

Structure fire calls are down slightly compared with 2016, but the total of all calls — including trash fires, burning brush and nearly 20 other categories, many of which are outdoors — grew from nearly 3,000 in fiscal year 2015–2016 to almost 4,500 in fiscal year 2022–2023.

(The department tracks activity based on the city’s fiscal year, which runs from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30.)

Trash and dumpster fires have more than doubled since 2016, and brush and tree fires also are up, according to data provided by Grego.

As to the spike in fatalities, Grego said, “It’s not a clear picture,” but if fire officials could identify a reason for the increase, “we’d do something about it.”

Grego said in most structure fires, the usual suspects are probably involved — an errant cigarette, an unmanageable cooking fire, a defective extension cord or space heater.

When a fire occurs, an incident commander will look for where it started and how. A fire department investigator is called in when the cause is not immediately clear, and also if arson is suspected, if it’s related to a drug lab, when anyone is injured, or the response required a large number of vehicles and personnel.

The number of fires requiring an investigation each year has risen from 65 in fiscal 2015–2016 to nearly 400 last year.

The deputy chief said a majority of fires in the city are occurring outdoors and added, “Where we’re seeing the increase of that is … along the freeways, along the railroad areas, inside abandoned structures, vacant structures, along the waterways.”

The growth in the number of unhoused people living in the city may in part account for that, Grego said.

The deputy chief said he didn’t want to give the impression “that we’re blaming (unhoused people) or picking on them,” and noted the overall increase in the number of fire calls and investigations in the past several years.

Homeless advocate Christine Barry, a Long Beach resident who runs a nonprofit that assists unhoused people, said that last year someone set at least six fires by Recreation Park, and there have recently been numerous trash can and dumpster fires.

Christopher Lasley, who was homeless off and on in Long Beach for about 10 years, said in a phone interview that fires “are a very common thing, especially for cooking out on the riverbed,” but that in encampments they can also be a form of retaliation.

“I can think of a handful of times when I myself, when I was homeless, went through and burned somebody’s tent down because they stole my (stuff),” he said.

In September, Lasley was set to graduate from rehab after completing a prison sentence.

As to the deaths in abandoned buildings, Lasley said more people have been seeking shelter in them because “they have nowhere to go — the city took everywhere they had to go away from them.”

While there’s no silver bullet to reduce the incidence of fires, Grego said there are things fire officials can do.

They work with code enforcement and the police department to get abandoned buildings secured or torn down. The city just held a disaster preparedness event that the fire department took part in. They have a program to provide and install smoke detectors for residents whose homes or apartments don’t have them.

And they’ve pursued people who deliberately set fires, more than doubling the number of arson arrests in the past four years to about 91 arrests in fiscal 2022–2023, Grego said.

“The good news is that those that are the bad people, we’re arresting them,” he said.

Barry, the homeless advocate, believes more police patrols would help. “We’re so short on cops that the patrolling is down, which creates more of an opportunity,” she said.

Grego said he wants the department to step up efforts to talk to residents about fire prevention.

“We definitely need to maybe go back to some of the basics,” he said. “This might be our opportunity to take five minutes to educate people on smoke detectors (and) fire extinguishers.”

Staff writer Fernando Haro Garcia contributed to this report.