An answer to Long Beach’s ongoing budget woes may be buried under dust in Sacramento.

The Long Beach City Council is in a mad dash to bring the state to the negotiating table over a decades-old contract that establishes the revenue split from the Wilmington Oil Field in and around the coastline, saying the current agreement has been a cash gusher for the state.

City officials say time is of the essence, as the legislative cycle ends next week and any items not brought forward could be tabled until at least January.

It’s an item that would restructure how much the city receives for its guardianship over what’s known as its tidelands area, a 24-square-mile swath of ocean and coastline from the Orange County line through downtown Long Beach to the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. The field goes about as far north as Ocean Boulevard, almost reaching the breakwater to the south, and encompasses some of Long Beach’s most precious assets: the beaches, marinas and Convention Center.

Since 1991, the city has received 8.5% of revenues earned through oil and dry gas production in the tidelands area, pulling from the Long Beach section of the Wilmington Oil Field. Another 49% goes to the oil operator while the state takes 42.5%.

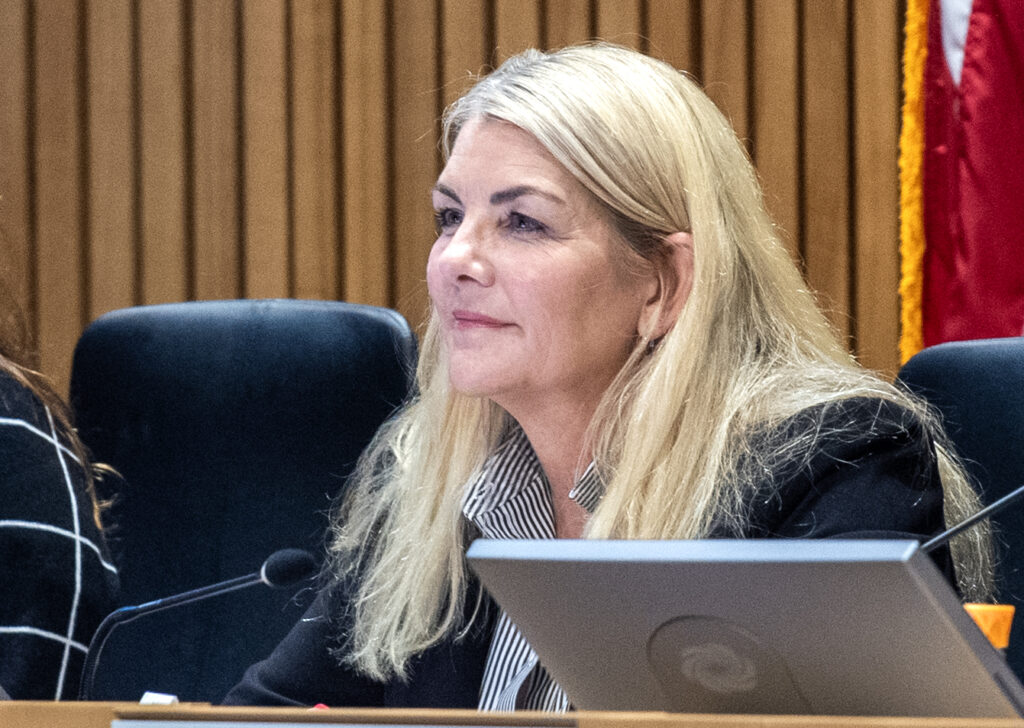

But it’s a deal that no longer makes sense, according to Long Beach Councilmember Kristina Duggan, who said Friday a reasonable city share rests between 20% and 30% of the revenue.

The city is under mounting pressure to transition its economy away from a reliance on local oil production, which is set for a dramatic decline — $300 million over the next 10 years, according to City Auditor Laura Doud. Meanwhile, the city has $1 billion in outstanding coastal projects, from a deteriorating Naples Island seawall to costly upgrades at the Convention Center.

Facing a rising cost of upkeep along the coastline, the city is expected to spend more than it earns to oversee the tidelands for the first time in 2026. Officials project future deficits through 2035 will range between $6.2 million and $10 million.

As a result, city leaders may have to divert money from other core programs and services.

“What are we going to take away? Are we going to take away our libraries? Are we going to take away our staffing at parks? Where are we going to get the money when we are using funds from the general fund to take care of every district?” Duggan said.

Meanwhile, the state expects to reap $271 million from the tidelands through 2035, according to Duggan’s office.

Oil in Long Beach has a long, intricate history, pieced together through multi-party contracts and court hearings over who is most deserving of the gushing revenues and by how much.

Oil was discovered in 1932 and was estimated to total 9.5 billion gallons worth. In the years prior to 1955, Long Beach was awash in cash, keeping most of the oil revenue for its general fund.

Citing a trust arrangement set in 1911, the California Supreme Court in 1955 named the state as the main beneficiary, since the oil was extracted from state land beneath the water. The state declared most of the money generated from oil production as surplus and began redirecting it to Sacramento, based on the conditions when the coast had fewer needs and oil production was much higher.

Under the expectation that oil would either soon dry up or be phased out, the city agreed to a funding formula in 1964 that fixed its revenue at $1 million a year. The change in 1991 bumped the city’s yield to its current rate, which now brings in around $50 million annually. The city receives tax revenue from 2,762 active and idle oil wells that are managed by 14 oil operators.

But the current formula is out of step with reality, Duggan said, adding that the state has taken $5.75 billion from Long Beach under this formula as “surplus.” “Our increase in responsibilities and costs is escalating far, far greater than what we can keep up with,” she said.

It’s the “number one priority this next year” in state lobbying, said Mayor Rex Richardson on Tuesday. The Mayor has for years lobbied the state to allow Long Beach to divert interest from a fund meant to cover the costs of decommissioning defunct oil wells, of which the city has invested millions.

“We’re going to go back to Sacramento and put options on the table,” Richardson said. “But the reality is, … doing nothing is not an option for us.”

In a joint call with the governor’s office last week, Richardson reiterated his request for diverting interest from the oil decommissioning fund, while Duggan spoke on renegotiating the funding formula.

While Newsom’s office seemed open to both ideas, according to Duggan, each needed to be championed by Long Beach’s state representatives — state Sen. Lena Gonzalez and Assemblyman Josh Lowenthal.

“We need them to carry this,” Duggan said. “And we have two weeks to get some sort of traction with legislation. That’s the only way to make it happen.”

In a statement Friday, a spokesperson from Lowenthal’s office said the assemblyman looks forward to “discussing potential ideas with the City of Long Beach and the Long Beach legislative delegation.”

“With California now facing a major budget shortfall, we’ve had to make tough choices to protect vital services while keeping the budget balanced,” the statement read. “Any sudden changes to that balance could have real consequences here at home. While the city has and continues to be a good steward of the state’s tidelands — any discussions surrounding the fund’s future must be well-informed, conducted responsibly, and be in the best interests of the entire State of California and the residents of the City of Long Beach in order to uphold the public trust.”