Stephen Downing, who redefined when Los Angeles police officers can use deadly force, transformed public perception of law enforcement through shows like “MacGyver,” and whose reporting inspired reforms in Long Beach, died on Nov. 20 at Long Beach Memorial Hospital. He was 87.

The cause was sepsis, according to his family.

For more than 30 years, beginning in the mid-1960s and extending through the 1990s, television viewers with a penchant for cop drama could hardly go a week without running into a show touched by Stephen Downing.

His writing credits span more than 500 hours of television, primarily crime dramas, starting as technical advisor on “Adam-12” before writing scripts for Hollywood producer Jack Webb’s “Dragnet” and “Walking Tall,” and he is listed as producer and showrunner for nearly a dozen series, some long-running hits like “Knight Rider,” “F/X the Series,” and the “RoboCop” TV show.

Downing’s crowning television achievement was as showrunner for “MacGyver,” which debuted in 1985.

Those familiar with its origin story are quick to tell it: Downing is the one who made the call that Angus “Mac” MacGyver, the show’s namesake protagonist in a leather jacket, wouldn’t carry a firearm, instead arming him with a dual college degree, creativity and a Swiss Army Knife.

It was an “atypical” action-adventure show with “two regular characters” and one that “didn’t rely on violence,” said Rick Drew, a Canadian television writer who joined the series in season three. “As a result, it pushed us more towards character-driven stories.”

Under Downing’s guidance, storylines had MacGyver protesting alongside Latino farmhands against greedy vineyard owners, conducting research at a school for deaf children and protecting the endangered Black Rhino. At one point, MacGyver even becomes vegetarian.

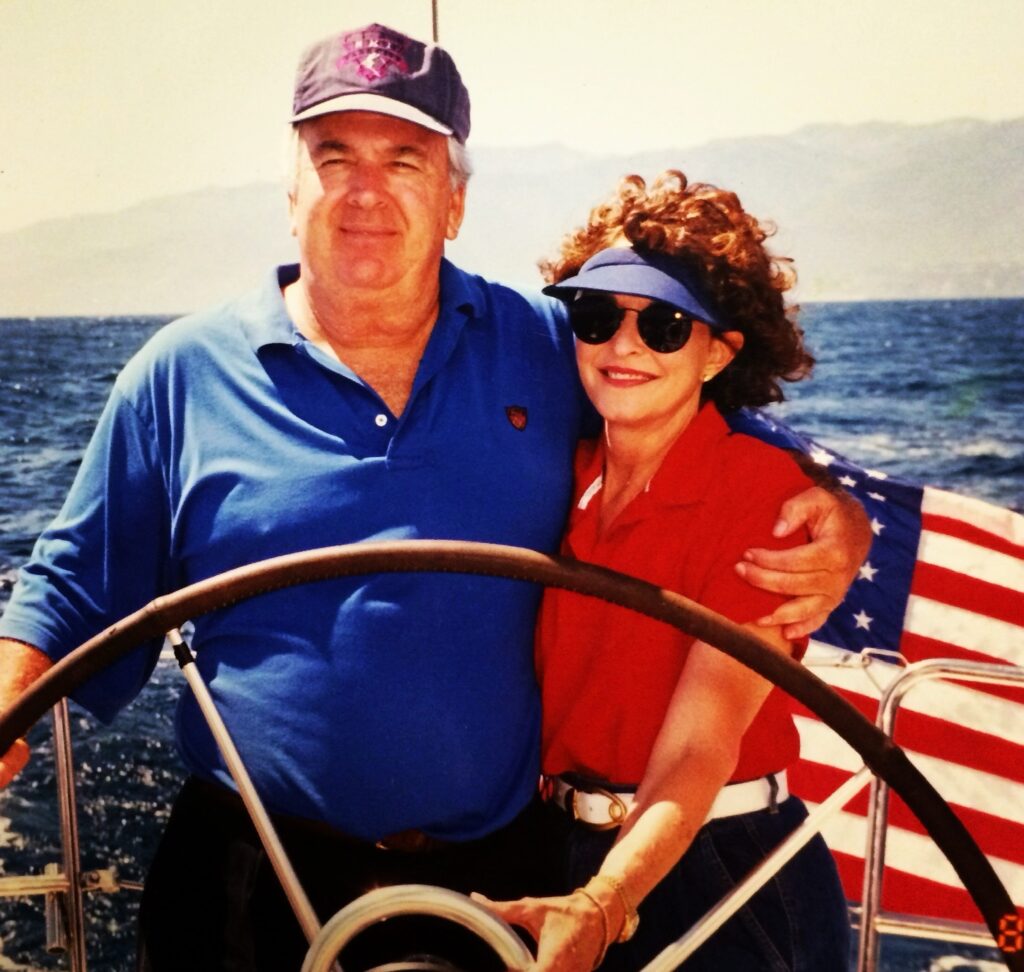

The show was a family operation for Downing, with wife, Adrienne, as the show’s publicist, and his daughter, Julie, acting in several of the episodes, most of which were shot in Vancouver.

In many ways, Downing’s own success mirrored some of the formula he repeated in so many of those episodes. It was a three-act, feel-good story of humble beginnings, a daunting problem and a creative, non-violent approach using wit and virtue to solve society’s problems.

Born in 1938 in Hanford, Calif., Downing was the son of a farmer and a homemaker. Along with his brother, Roderick, he helped his father pick cotton and citrus near their ranch house.

As a young man, he became a forest ranger, building trails in the Sierra Mountains. He later became a surveyor, laying out the runways his grandson, an F-18 fighter pilot, would eventually land on and exit from Naval Air Station Lemoore.

At age 18, he met his wife, Adrienne, at Mearle’s Drive Inn in her hometown of Visalia, about 20 minutes east. The two wed a year later and had their first child a year after that.

At 21, Downing joined the ranks of the Los Angeles Police Department in 1960, starting as a patrolman for its 77th station, the precinct for South Los Angeles.

Almost immediately, Downing would later say, he was met with dishonest supervisors and an overarching air of corruption that loomed over the department.

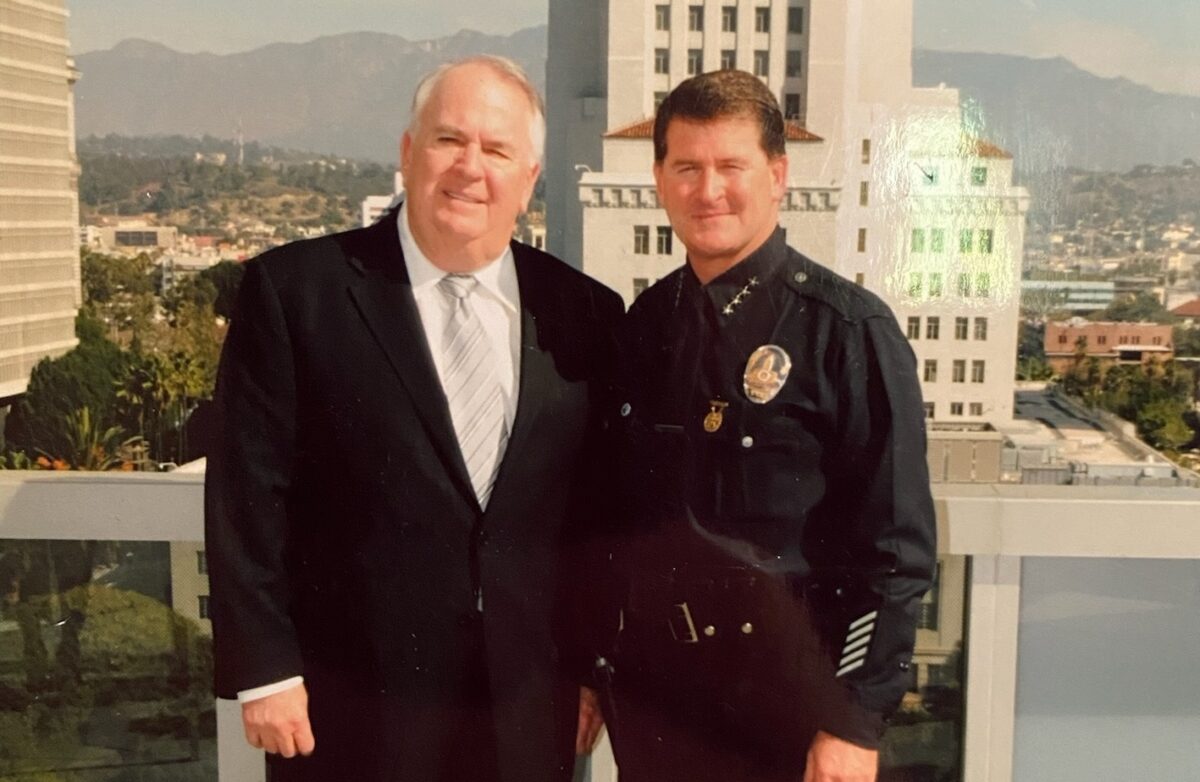

As his son Michael Downing — a former LAPD deputy chief — tells it, his father vowed early on to outrank those “bad apples” and to fix the problem from the top down.

In 1965, during the Watts riots, Downing was a sergeant. He was on the street as Black Americans, sick of years of abusive treatment by the police, kicked off an uprising that lasted for six days, leaving 34 dead, 1,000 injured and nearly 4,000 arrested.

It was also the year he began writing for television, under the first of three aliases he would use for the next 15 years: Michael Donovan, Sean Baine and Adrian Leeds.

In the LAPD, He advanced quickly, from sergeant to lieutenant, then to captain, commander and finally, after 18 years on the force, became Deputy Chief of Personnel and Training at age 39.

As a member of the department’s review board in the late 1970s, he helped enshrine rules and disciplines for officers using deadly force — rules that, despite his high rank, he insisted on personally teaching to recruits in training academies.

Downing’s opinions of the department remained mixed between a love for his fellow officers and their mission, and what he saw as corruptible leadership and wasted efforts on the War on Drugs.

“He had an abiding sense of justice,” said Diane Goldstein, a friend and former officer. “He was fiercely loyal to the policing profession. He recognised the faults of policing but believed in that inspirational goal that we can always do better.”

His convictions further deepened following the death of a fellow officer in an undercover drug sting in 1973. Decades after he retired from the LAPD in 1980, and nearing the sunset of his television career, Downing joined the Law Enforcement Action Partnership, formerly known as Law Enforcement Against Prohibition, in 2011.

From this platform, Downing became a staunch critic of drug enforcement, sharing his belief in newspapers and magazines that the policy of prohibition ought to be abandoned as a failure, that drug abuse be treated as a medical problem like alcoholism and that bringing results must not simply serve someone’s campaign cycle.

“The earlier experiment lasted less than 14 years, but today’s failed prohibition was declared by President Nixon 40 years ago and has cost our country more than $1 trillion in cash and much more in immeasurable social harm,” Downing wrote in a 2011 Op-ed for the L.A. Times.

A year later, Stephen Downing helped drive the “Caravan of Peace” from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., in protest of the drug war in Mexico.

Those with the organization said they helped take law enforcement’s drug policies “kicking and screaming into the 21st Century.” These views weren’t always popular among Downing’s fellow officers.

“Both Steve and I have probably lost a tremendous amount of friends from law enforcement, in some ways,” Goldstein said. “Because we stuck to our principles and our values that the role of someone within policing should also be to dissent and to hold our own organizations accountable to the rule of law.”

More recently, Downing criticized the use of masks and unmarked vehicles by federal immigration authorities, saying it “erodes public trust” and creates “the very conditions in which abuse thrives.”

“We don’t have to treat our citizens as enemies, but because he wasn’t afraid to call people out, it angered people,” Goldstein said.

Downing’s crusade eventually took the form of news stories in a recurring column for the Beachcomber, a local biweekly newspaper in Long Beach with about 33,000 subscribers.

He was referred to the paper’s longtime editor, Jay Beeler, who watched Downing’s writing develop over the years into a thoughtful column on the goings-on of the Long Beach Police Department and local government.

According to Beeler, Downing’s copy was a refreshing break from the typical egoism and tardiness of many writers. Stories were clean — sometimes a little long — but timely and rarely needed a correction.

Using what many believed was an expansive network of sources inside the Long Beach Police Department, Downing’s reporting, at its height, brought international attention.

In 2018, he worked alongside the ACLU and Al Jazeera to uncover the LBPD’s secret use of the disappearing messaging app TigerText. The story drew protest and reprisal from defense attorneys and civil rights activists despite the city’s conclusion that TigerText didn’t run afoul of any laws or local policies.

His reporting inspired the work of local advocacy groups, including after his 2017 story on a roadside altercation between then-Councilmember Jeannine Pearce and her former chief of staff, Devin Cotter, which led to accusations of domestic violence, preferential treatment by the police, and several ethical violations.

“Nobody would have known about this” but for Downing, said local political consultant Ian Patton, who credits his reporting for inspiring Patton to launch a recall campaign against Pearce and later form the Long Beach Reform Coalition that still frequently spars with city government.

In his final years, Downing continued writing about Long Beach.

His last story, which ran in the paper’s Nov. 14 edition, criticized the city government and Belmont Shore Business Association’s response to a late-night murder on La Verne Avenue, his home street.

It’s a response he summarized — with a style he took his whole life to forge — in the closing line on Page 6:

“Belmont Shore doesn’t need another round of condolences or coordinated press releases,” he wrote. “It needs collaboration — the kind that meets neighbors face-to-face, embraces transparency and expects every stakeholder to take responsibility for the community they share.”

“Until that happens, Belmont Shore’s ‘unified voice’ will continue to sound like three separate monologues — one from residents living the problem, one from businesses denying it, and one from City Hall trying not to choose sides.”

Those close to Downing described him as a son of California, a generous boss, a virtuous policeman, a writer of genuine power, a caring father and a loving husband. He is remembered for his sailing trips to Mexico and Greece, for referring in reverence to wife Adrienne as his “bride” long after their marriage, and for teaching audiences worldwide that violence should only come as a last resort.

He is survived by his wife, Adrienne, of 67 years, along with two daughters, Tambree and Julie; a son, Michael; six grandchildren, three grandsons-in-law and six great-grandchildren.