I occasionally use this column to investigate relatively simple methods to make homes more environmentally sustainable. This can begin with questions of design, so that a home makes the best possible use of natural light, or questions of construction, like selecting materials and building methods that minimize environmental impact. In

A major use of electricity for businesses and households in

I recently attended a housewarming party for some friends at the new Olive Court development, located at

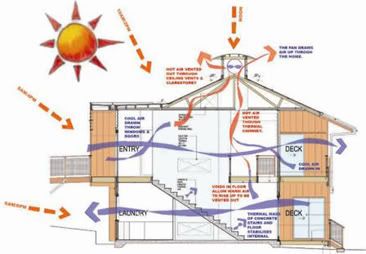

For centuries, homes have relied upon various passive cooling and heating strategies that take advantage of simple thermodynamic character of rising hot air and descending cool air. In arid and tropical climates, where summers are often more brutal than winters, vernacular architecture often focuses attention on passive cooling design techniques. Bungalow architecture, originally developed in

Various techniques for employing passive air conditioning also exist, such as cooling air using geothermal energy by sending it through ducts below ground before entering the home or capturing wind in towers that are then cooled by water misters where it descends into the main building. Thermal chimneys work in the opposite manner; a tower or vertical shaft is used to expel hot air, often by heating it further so that it rises out of the structure, creating a suction effect that draws in cool air below. Modern variations of this time-tested practice use the latest technology to further improve on the general concept.

The simplest methods are often the best, in part because they require little maintenance and can often be used to retrofit existing structures. In my friends’ townhouse, the stairs and hallway are in the center of the home, allowing for cross ventilation. The operable skylight over the stairway allows for hot air to travel out the roof. Because it allows light to enter, the skylight also provides solar heat to increase the rate that the air travels, increasing the suction effect drawing cool air into the house.

My friends’ townhouse is not one of a kind. In fact, most two-story homes have a centralized stairwell that could be reinvented as a passive thermal chimney. Of course, as is the case whenever creating new penetrations in a roof, it is important to have a trained professional install the operable skylight to avoid leaks. One should also know where air registers for any existing central air conditioning system are located: it would be self-defeating if mechanically air-conditioned air was blown directly out the newly installed skylight.

Their home has additional features that help also passively cool the home including windows on at least two sides of each room allowing for natural cross ventilation. The dwelling unit is also planned around an enclosed patio area that opens to the East, avoiding the greater heat of the afternoon’s western sunlight. Due to the solar mass from the cement plaster creates a cooled space that transfers the cooling effect though the walls and ceiling.

The townhouses of

Thermal chimney diagram (courtesy of Sustainable Home