When artist Danielle Eubank embarked on her first sailing expedition, a 10,000-mile journey aboard the Borobudur, an 8th century Indonesian trade ship replica retracing an ancient maritime trade route from Indonesia to Africa, she learned something about herself. She gets seasick. Very, very seasick.

“The first time was rough. I didn’t know that I got motion sickness, because I had never had car or plane sickness. I can read in the back of a car without any trouble,” the painter said over the phone from her studio in Los Angeles. “But I was just standing on the boat, talking to the captain and all of a sudden I needed to vomit.”

It’s a pretty inconvenient truth for the artist, given the subject matter Eubank has devoted herself to painting: the ocean.

Aside from enjoying the artistic challenges rendering water presents—she says motion sickness medication and pressure-point wristbands seem to (mostly) do the trick—what has propelled the painter to stomach crippling waves of nausea for the last two decades of her life is her mission to raise awareness about ocean pollution and climate change by painting every ocean on Earth.

Eubanks decades-long quest to capture the bodies of water for her project, “One Artist Five Oceans” has taken her around the world on four sailing expeditions extending over 30,000 miles across all five of our oceans.

Now, for those of you readers who just raised an eyebrow, yes we know, five oceans sounds a little strange. There’s only four, right? Well, technically yes and no. Firstly, the ocean is just one ocean, but for geographical purposes they were defined into the four we’re all familiar with: Pacific, Atlantic, Indian and Arctic. In the last few decades, though, the Southern or Antarctic Ocean, which is a growing body of water surrounding Antarctica has been defined by scientists as an ocean, although its classification hasn’t been universally accepted. Make sense? Okay, read on.

In Mozambique, she’s seen first-hand the haphazard excess of plastic waste and garbage. In the Arctic, she witnessed tiny rock islands poking out from the water, confirmed by scientists on board the expedition as evidence of warming oceans and melting polar ice caps.

With each expedition and consequent body of work, she’s traveled internationally speaking at universities and climate change conferences to share her experiences and observations. Currently, a collection of her paintings are on display at the Aquarium of the Pacific. “Ocean Resiliency: The Exhibitions of Danielle Eubank,” is somewhat of a retrospective, featuring 24 of her paintings, some being high-quality reproductions.

They all represent the different oceans, she says, and many of the reproductions are paintings people have never seen because they were sold years ago. Alongside each illustration are note cards that offer tips and suggestions of small, everyday things people can implement in their lives that can help mitigate climate change.

“I want to change the vocabulary,” Eubank said. “I don’t want people to talk about doing things that help the environment as some kind of onerous task.”

Continuing with that idea, Eubank has organized a 12 Day Environmental Challenge, a call to action to make a more positive impact on our environment for the remainder of the holiday season. On each 12 Days of Christmas (from Dec. 25 until Jan. 5, 2020) she will announce a task, something accessible and easily photographable to do over social media that can help our oceans and mitigate climate change.

Things like unplugging your electronic devices when they’re not in use. Washing your clothes with cold water. Turning your thermostat down just two degrees and using a reusable water bottle to drink tap water. After, she’ll choose three winners who participated every day to receive a signed, limited edition, matted photograph of Antarctica, captured by the artist.

“I think we all feel a little demotivated with all the bad news about the climate and the environment,” she said. “So my goal is to help people feel more empowered.”

During the earlier decades of Eubank’s expeditions, first onboard the Borobudur and after the Phoenician Ship Expedition—another replica, this one a 6th century BC Phoenician sailing vessel that re-created the first circumnavigation of ancient Africa (proving that Columbus was not the first who could have done so)—the artist acted as a crew member, with all the required duties as such.

Minding the helm, which was in part helping secure the boat, keeping watch—sometimes for six to eight hours—eyes peeled for obstructions or any larger ships that may not see them, cooking, cleaning and pumping the bilge, which required manually pumping any water that may have washed aboard the deck.

“It’s 24 hours, the ship doesn’t just stop at 5 o’clock or something,” she explained with a laugh. “There are different watches, different teams of people that work different hours. So, you might be doing something, then it’ll be your turn to do those tasks and then after you’ll have time off for sleeping, or in my case, sketching.”

Working almost exclusively with oil paint, using traditional oil coated linen as her canvas, Eubanks prefers to sketch from life. She would work quickly, sketching out her observations of the water or the landscape with charcoal, then build layer after layer of paint, rubbing off and reapplying using brushes, rags and her hands, until she could get the desired color and texture.

If weather conditions weren’t favorable, say heavy rain or snow, she’d photograph and use the images for later reference.

“I love painting in oils,” Eubank said. “I sketch in it. I paint in it. It’s very easy to work with, it’s very forgiving, and the colors dry pretty much the same color as when they are wet. I like sketching in it because if I want to work one of the sketches up into a painting, I know I’m going to get exactly the same colors.”

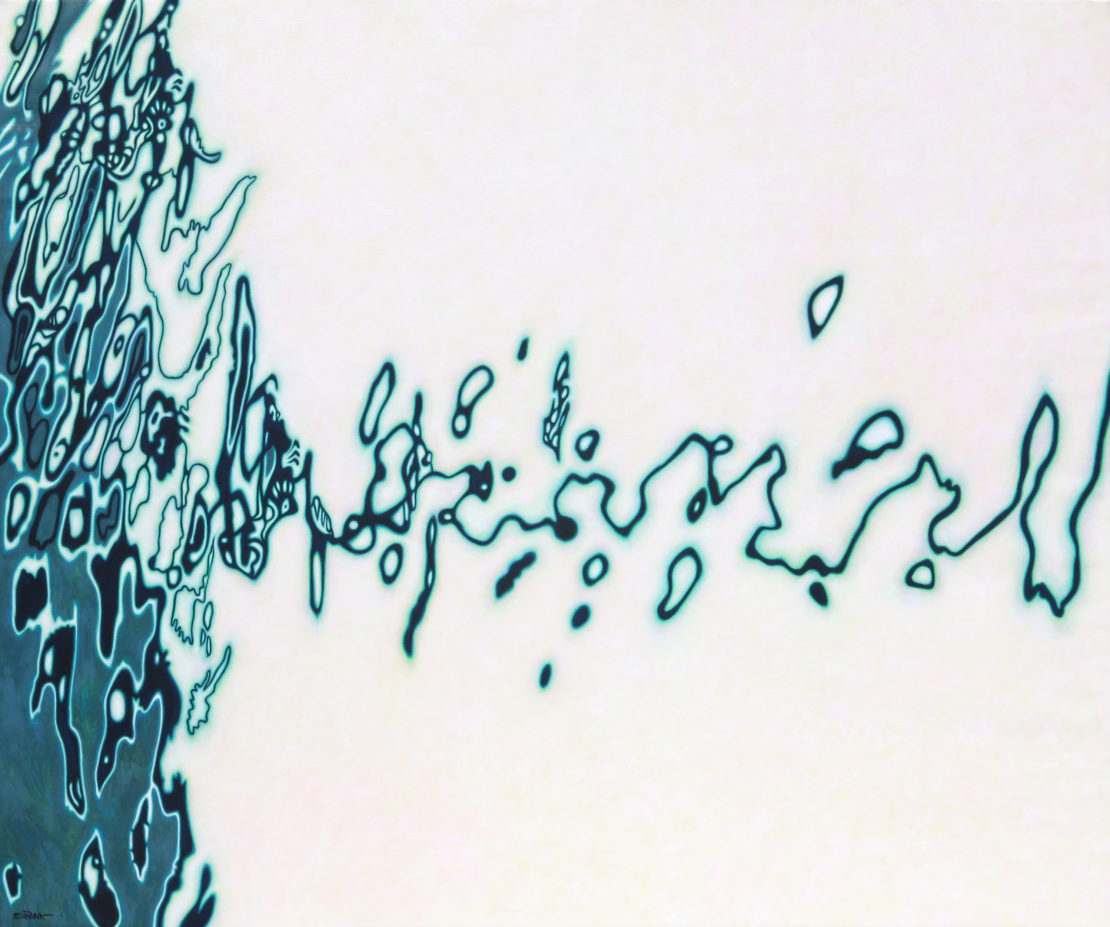

Eubanks art straddles the line between realism and abstract, self-described as “emotive formal paintings.” It’s impossible to capture an identical replication of water when sketching from life. Because, well, moving water. Instead, she’s learned to abstract the water with formal shapes, lines, colors and textures to embody a feeling, a thought or a moment she experienced during her travels.

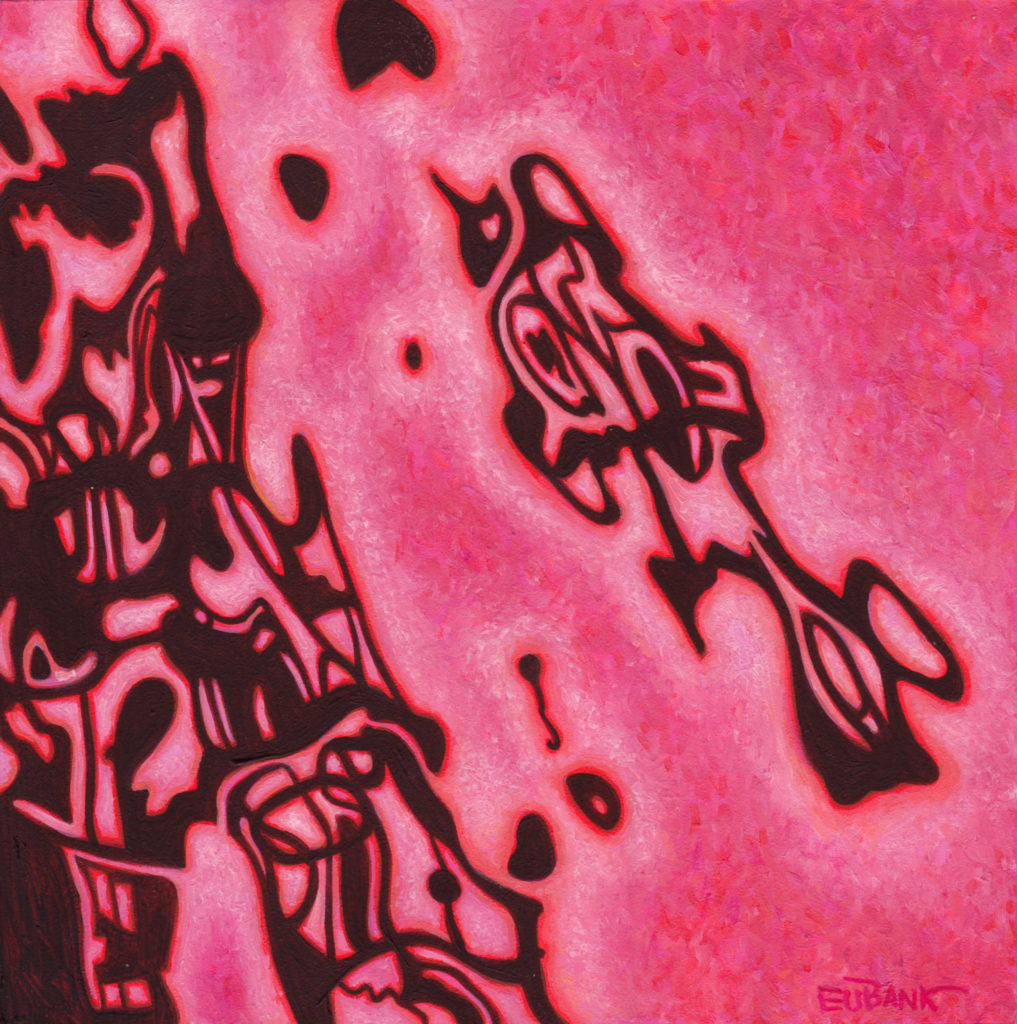

On board the three-masted tall ship, The Antigua, she sailed with The Arctic Circle, an expeditionary program that puts scientists and artists together to explore the High Arctic. She recalled the unique pink color that would reflect from the snow-tipped mountains during the last hours of sunlight. She recreated this in her piece, “Arctic VIII,” a bright, undulating painting with bold pinks, reds and thick black linework.

Culminating the end of her adventures was her most recent trip to the Southern Ocean, or the Antarctic Ocean early this year. She embarked from Ushuia, Argentina and for two weeks sailed across the Antarctic Circle, visiting islands along the Antarctic Peninsula.

She sketched all manner of water, ice flows, and icebergs. She captured the mountains and whatever wildlife she was lucky enough to see.

“It was pretty much the best place that I’ve ever been,” she said.

There was never a moment of trepidation during Eubanks travels where she ever considered calling it quits. Not during bouts of crippling seasickness. Not in Syria when she found out her nausea wasn’t seasickness, but actually morning sickness (after, she did take a break to raise her now 10-year-old daughter). Not even when gale-force winds, howling through the Mediterranean beat against the replica Phoenician, waves churning it caused the ship to rock violently.

“I’d see the ocean on one side and then a second later I’d see the ocean on the otherside,” she recalled. “We were tilting and yawing a lot.”

Although Eubank doesn’t have any plans for another sailing expedition yet, she envisions a trip to the great Pacific garbage patch, an enormous mass of plastic and floating trash that, according to researchers from The Ocean Cleanup project, extends nearly 1.6 million square kilometers. She imagines it will be a depressing sight, but she wants to do what she does best, paint it and capture that emotion.

“Ocean Resiliency: The Exhibitions of Danielle Eubank” is on display until Jan. 5, 2020 at the Aquarium of the Pacific; 100 Aquarium Way.