Evelyn Knight sat transfixed in horror by the grainy images on her black and white TV. It was March 7, 1965.

Deputized white Alabama cops, joined by thugs wielding nightsticks, charged a group of protesters at the bottom of Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. The marchers were attempting to walk 50 miles to Montgomery, Alabama in protest of the killing of a young black activist by police as well as the ongoing obstruction of their right to vote.

After a warning, police and their posse charged, followed by tear-gas canisters and more police on horseback riding into the fray. Seventeen protesters were hospitalized and 50 more treated for injuries.

“I watched it on TV and I got madder and madder,” Knight said. “I was convinced I didn’t need to be in Long Beach.”

It is a story Knight has told many times over the years.

Martin Luther King Jr. would put out a call for others to join him in Selma and march to Montgomery, focusing the nation on the brutality of suppression in the South. The marches are credited with leading to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Those who know Knight would expect nothing less than for her to be in the midst of it all.

Whether as a founding member of the Long Beach Community Improvement League, as a teacher of Black Studies at Cal State Long Beach, organizing against polluters in West Long Beach or holding discussion groups in her home, Evelyn Knight has always been outspoken and involved.

Ask anyone, Evelyn Knight has always been there.

If it’s an issue she feels strongly about, she says, “I talk about it. People tell me to shut up. I don’t listen.”

But in the case of Selma, it wasn’t enough to talk the talk, you had to walk the walk; Selma to Montgomery.

Teaching future leaders

“She was always encouraging students to be active in the community as well as in academics,” said Willie Elston, a student and mentee of Knight’s when she taught at Cal State Long Beach in the 1960s, a time when she was among the vanguard of its black and ethnic studies programs.

“You had to give back to the community,” Elston said. “She was always an advocate of that.”

Elston remembers a class with Knight called Game Theory which taught students how to turn their academic understanding of issues into practical, organizational theory and how to work with varieties of people and programs.

A number of Knight’s students, such as Erroll Parker and Ahmed Saafir, would go on to be, and still are, major figures in Long Beach’s African American service community.

A native of the Africatown area of Mobile, Alabama, Knight grew up steeped in civil and equal rights advocacy.

Mobile was where the infamous Clotilda, the last known ship to smuggle slaves into the United States, delivered its last human cargo in 1860, more than 50 years after the practice had been outlawed. Knight grew up among the descendants of that ship, who founded Africatown after the Civil War.

She remembers segregated water fountains and sitting in the backs of buses as well as the other subhuman treatment of blacks that was de rigueur during the Jim Crow era.

“I was born into movements,” she said. “People were always fighting for rights down there.”

And Knight carried the struggle wherever she went.

She was there helping to integrate an all-white school district in the Florissant suburb of St. Louis in the 1950s as a teacher. And yet, she was shocked when she arrived in supposedly progressive California as a supervisor for Catholic Family Services in 1962, to find “racism was really, ‘Wow! Long Beach was different from L.A. It was a smaller town and white people didn’t want us to live here.”

Knight learned that blacks were essentially confined to the Central Area of Long Beach.

“It was horrendous, and it was non-negotiable. Blacks all stayed in their area.”

As she and other activists began pushing for reform, she remembers whites warning about “people who bucked the system.” The warnings were borne out, she said, when neighbors used hoses to flood out the home of a black family that moved into Bixby Knolls. But rather than shrink, Knight and others met the challenge. After all, she was born for this.

Founding member of Community Improvement League

Knight was part of a group that met in the apartment of Earnest Preacely in Long Beach. In 1964, they created the Long Beach Community Improvement League, the oldest anti-poverty program in Long Beach.

Knight believes the best and most sustainable path out of poverty and inequality is education and the Community Improvement League’s first program was Project Tutor, which would lead to the organization becoming home to the first Head Start early learning program in the western states region.

Knight’s peripatetic activism would lead to stints in Baltimore and Richmond, California, where she was part of a group that worked with the social organizations, including the Black Panthers with their less publicized social programs, such as free breakfasts for children, senior escort service and busing families to visit relatives in prison.

Eventually, Knight returned to Southern California and settled in as executive director of People Coordinated Services in Los Angeles, which she worked until her retirement in 1997.

Of course, retirement is a relative term. Knight became a leading voice in West Long Beach with the East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice after a niece began to suffer from asthma. She still helps the Filipino Migrant Center on the Westside with social service and community organizing efforts.

“I want to teach kids to be community organizers,” she said.

Knight also plays host to discussion groups at her home in Compton, her den always stocked with snacks and bottled water, since, at any moment of any day, “I have people come by when they want to talk about issues.”

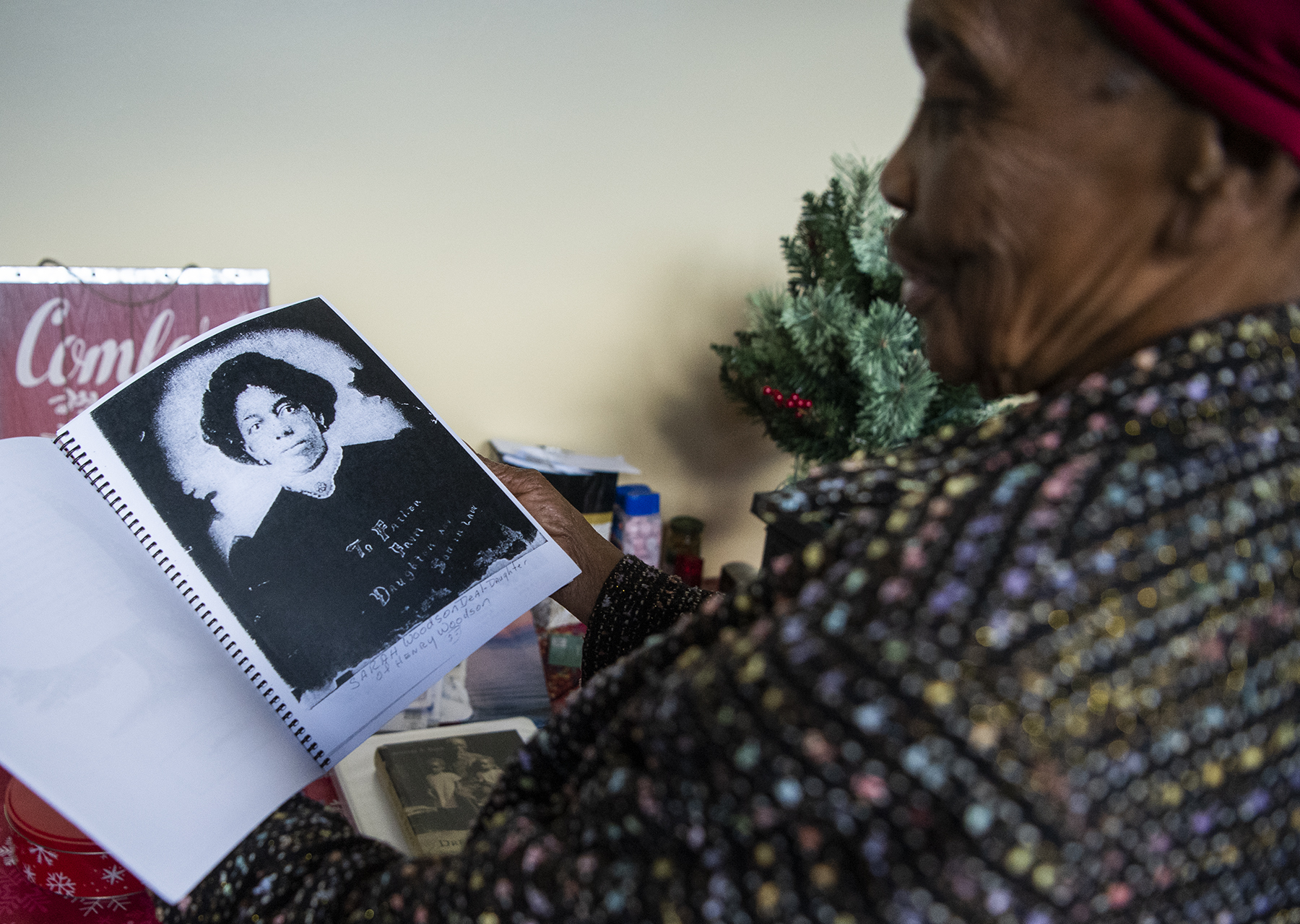

Visiting Knight’s home, which is on a half-acre in Compton in an area zoned for farming, is like stepping into a kind of Civil Rights time capsule. In her living room is a two-foot photograph of Knight at the first inauguration of President Barack Obama. Nearby is a copy of a Norman Rockwell painting, The Problem We All Live With, depicting six-year-old Ruby Bridges accompanied by federal agents, crossing the color line into an all-white grade school in New Orleans in 1960. Stacked in a corner are various framed certificates, proclamations and awards Knight has earned over the years.

In the den are collections of books, including several on African Americans and civil rights in Long Beach, in which Knight appears often.

She is now at work on her memoirs and genealogical preservation with the help of Long Beach historian and author Sunny Nash.

“It is massive, including 20-plus hours of oral history and publications, photographic and archival preservation, photo and artifact exhibitions, published catalogs and such,” Nash said in an email.

Nash said there are plans for several showings and a possible traveling exhibit.

At 86, Knight shows little sign of slowing down. She credits part of her success to remaining single.

“That’s why I’m able to do what I want to do,” she said. “I enjoy my freedom. I do what I want to do. I’m not happy doing what people tell me to do.”

A marcher’s memories

For all she has achieved over the years, the march from Selma to Montgomery remains a pivotal moment. After Knight was finished kicking the couch over the news about the Bloody Sunday conflict, she heard Martin Luther King Jr. send out a call for others to join him in Selma.

By Monday night, she was on a redeye bound for Texas with a connecting flight to Mobile where she intended to “borrow” her Dad’s car. On the plane, Knight met a group of ministers who were also on their way to Selma, via Birmingham where they had arrangements to be picked up by bus. Knight switched her ticket in Texas and spared Dad the surprise visit.

When Knight arrived in Selma, she said the city was filled with visitors and black families were out on their porches offering water and places to stay.

“We all went into the Brown Chapel and King fired us up,” Knight said. “We marched to the Pettus Bridge. We were singing and we were all excited until we saw the men with billy clubs. They weren’t a welcoming committee.”

Although the police were willing to let the march pass, they would not guarantee their safety and a temporary restraining order had been placed on the march. King asked his companions to kneel and pray, then returned to Selma.

The second march was called Turnaround Tuesday. That night, a white minister and rally goer were beaten to death in Selma by a group of whites. Three men were eventually arrested, tried and found not guilty.

After negotiations, the third march occurred on March 21. Protected by the National Guard, U.S. Marshals and the FBI, protesters staged the successful march to Montgomery, arriving on March 25.

Postscript

In the current political atmosphere, Knight said it is vital to stand up and be counted.

“I just want equality,” she said. “We need freedom for everyone instead of freedom for nobody, which is what is going on now.”

There is a story that Evelyn Knight tells less often that is nonetheless a fitting coda to the march to Montgomery.

According to author Charles Cobb’s “On the Road to Freedom,” at the time of the march, Lowndes County was 81 percent black, “but not a single black was registered to vote.”

However, in March of 1966, black voters got to test their newfound voting rights. And Knight was there. She said the election needed volunteers and a friend asked if she’d go.

Knight, who was living in Richmond, jumped into a yellow Chevy and, after picking up a couple of volunteers in Long Beach, drove cross-country to Selma.

On election day, the people of Selma voted in John Hewlett as the first black Sheriff of Lowndes County.

And Evelyn Knight was right there.