Vanndearlyn Vong, a rising Long Beach artist, yearned to learn from a man she’d never met.

As a first-generation Cambodian-American, Vong understood the precious legacy of the work created by Yary Livan, a traditional Cambodian ceramist.

Livan, who works and teaches in Lowell, Massachusetts, is considered one of only a few living masters still working in traditional Cambodian ceramics — an art form that was nearly lost in the country during the Khmer Rouge’s dictatorial reign.

“During my parents’ generation, the arts and really the culture was systemically destroyed during the genocide for four years,” Vong said. “And so seeing that master Yary is one of three left — and also our other traditional arts are really hanging by a thread.”

Vong connected with Livan and arranged to study under him, learning about the traditional imagery in Cambodian art and how to keep alive practices like firing ceramics in a wood-burning kiln.

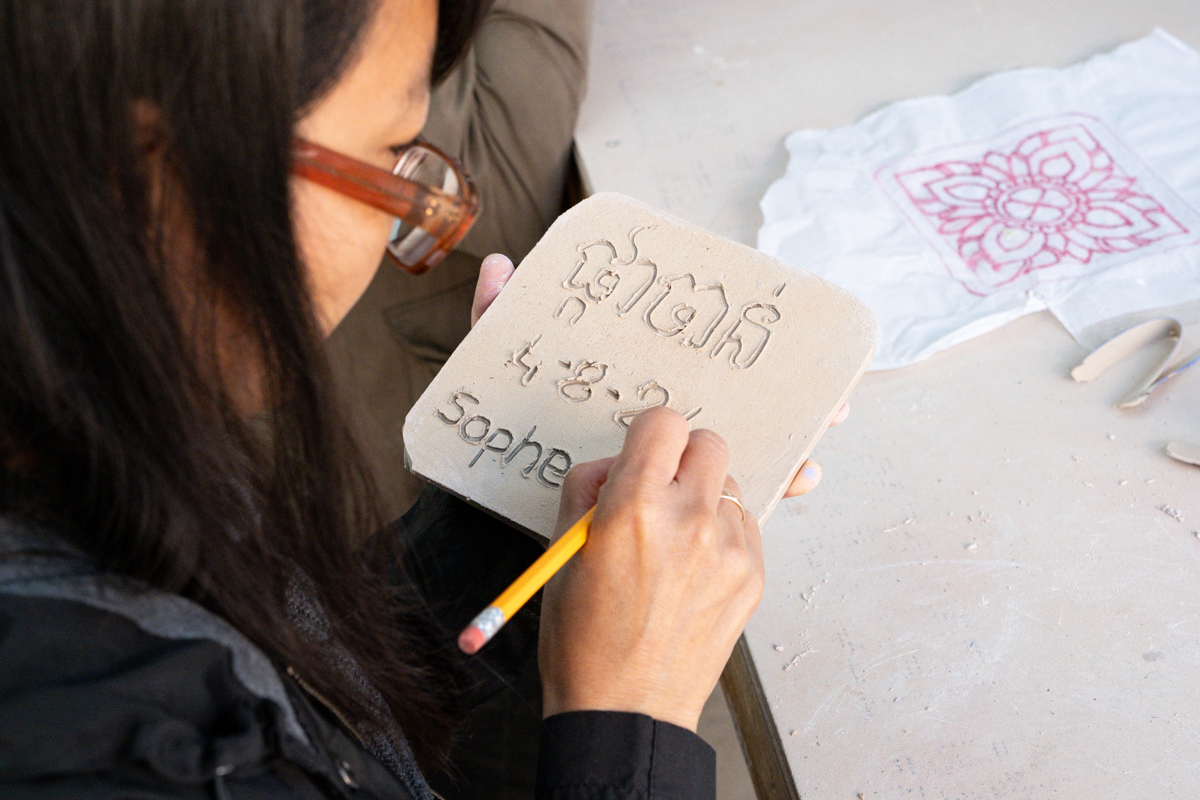

Earlier this month, during Long Beach’s annual Cambodian New Year, Livan shared his artistic legacy with a wider local audience. He came to the city and taught groups the basic techniques and importance of his practice while helping them hand-carve clay tiles with a traditional Cambodian design.

“I want to spread my artwork for all the people here,” Livan said in an interview.

Discussions of Cambodian history so often dwell on the infamous Killing Fields, he said, and he wants to show that there’s more. There’s beauty and pride, and a reminder that the Khmer people “love each other.”

The hand-carved designs in his work reflect the same images as in centuries-old temples, Livan said, monuments that were built in unity for a common purpose, not simply money as much modern art is.

Livan said he wants to show people a “Cambodia from the past. They have beautiful artwork.”

Ceramics are a perfect vehicle for this. They’re special, Vong said, because they “will outlast our lifetimes. And hopefully, keep the culture alive for the future generations.”