There are some in West Long Beach who still remember the deafening roar of hot rods and “funny cars” barreling down a tarmac at over 150 mph. Then, there are those who perhaps never saw the tire-screeching-rubber-burning-spectacle but still remember the cacophony caused by racing that echoed for miles.

“If the wind was right, we could be at home and hear the announcer,” said Rick Esparza about Lions Drag Strip, a historic quarter-mile racetrack in Wilmington that from 1955 to 1972, served as one of Southern California’s premiere drag racing destinations.

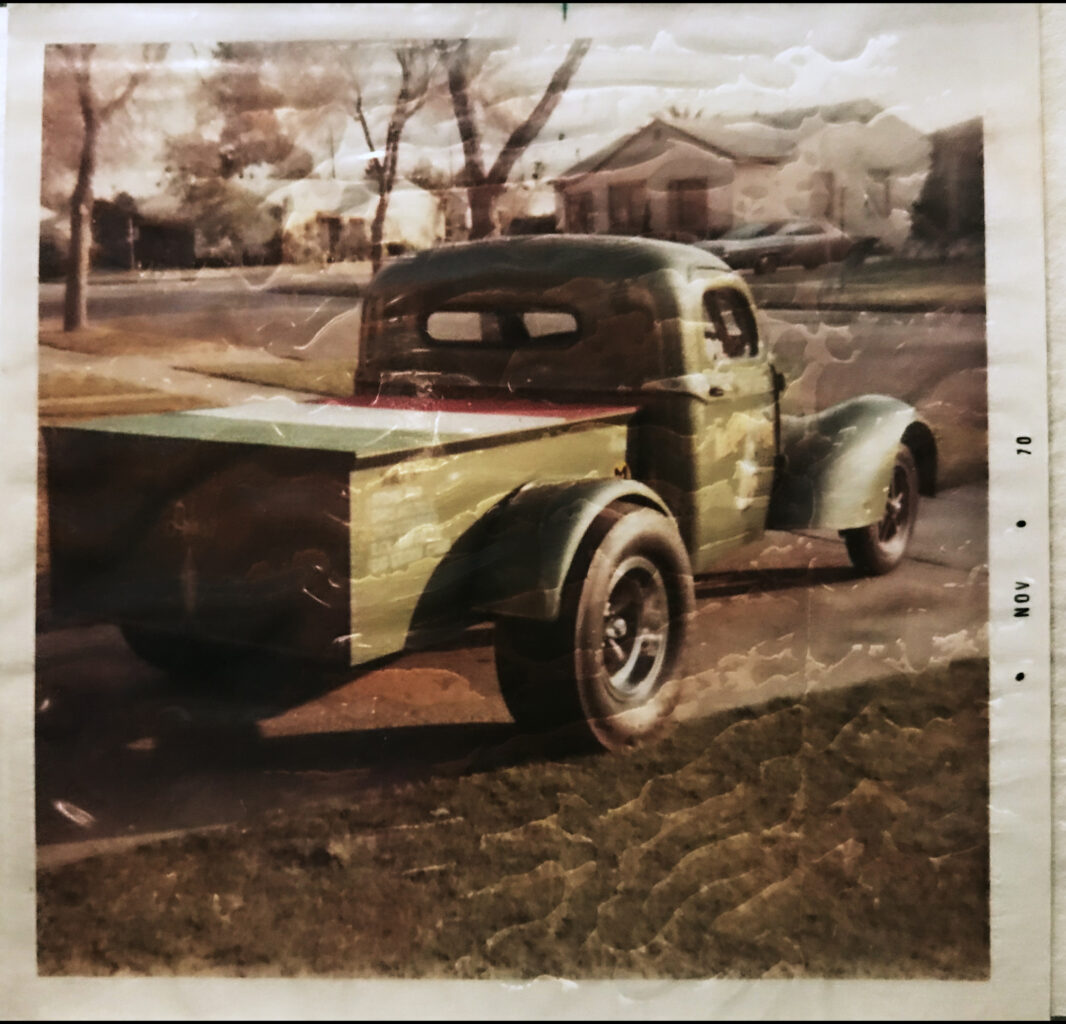

Brothers Rick and Fred Esparza remember those years well, not only as spectators, but as racers of the Mexican Express, a 1941 Willy’s truck they built into a hot rod and raced for seven years at Lions Drag Strip. Their driving accomplishments were not conventionally remarkable; they set no records, nor won any championships (though they got close), but a documentary about the brothers, released on Amazon Prime last month, delves into their passionate and life-altering love for the sport and the long past years of drag racing in West Long Beach.

“I think a lot of people remember, I just think it hasn’t been brought to the surface,” said filmmaker Danny Miguel, director of “Mexican Express.” “I wanted to make sure this film was the best it could be for the westside, for drag racing, just to pay homage to this wonderful culture and community,” he said.

Admittedly, Miguel didn’t know what to expect when he began filming “Mexican Express” three years ago. Before he became the director, he was asked to join in on “this race car story in West Long Beach” that a filmmaker and friend of his was pursuing. Miguel said that his own upbringing was part of why he was invited to help since Miguel has been living in Long Beach since infancy, when his father, a Navy man, moved into local Navy housing nearly 40 years ago and has lived in West Long Beach ever since.

Miguel’s connection to West Long Beach would also serve as a connection to the Esparza brothers; their father was a second-generation Mexican-American Navy man who had also relocated to West Long Beach because of his vocation in 1958. But unbeknownst to the Esparza brothers, Long Beach, particularly the westside, would become the stomping grounds of a drag racing renaissance.

In the mid-1950s street racing and hot rods had invaded the mainstream psyche with films like James Dean’s 1955 “Rebel Without a Cause”—and the actor’s death that same year—solidifying the sport into popular culture. Once quiet streets were now a thrill-seeking driver’s playground.

“There was a lot of racing back then on big streets, especially the westside,” Miguel said. “It wasn’t just street racers on Santa Fe Avenue, I think there was a lot of racing on the main streets of West Long Beach, like Atlantic and Cherry.”

Illegal street racing, and the grim headlines that often came with it, was a problem for local authorities. The city hatched a plan to create a legal space for racing by reaching an agreement with the Harbor to lease an abandoned train yard in Wilmington. With sponsorship help from Lions Club International, a local service club, Lions Drag Strip was built in 1955 at 223rd and Alameda streets where remnants of it still remain today.

“It got a lot of streets racers off the street,” Miguel said.

But it also awoke a new generation of enthusiasts, including a then-teenager Fred who fell in love with the sport by sheer proximity to Lions Drag Strip, which had become a major attraction drawing thousands of spectators to the area by the time he and his brother moved to the city.

And this is where “Mexican Express” dives right in. Anchored by the story of the Esparza brothers in their quest to “win at all costs,” the film spotlights a piece of local history—with plenty of archival footage—from the perspective of those who lived it and were personally transformed by drag racing for the better.

This was especially true for Rick, who struggled with bullying, fighting and racial tension in his youth before his brother convinced him to drop the trouble and get into racing.

“I could have been in jail,” Rick Esparza said if it hadn’t been for drag racing. “Sooner or later it would have happened.”

Much of the hour-long film features reminiscent conversations between the brothers as they revisit, 40 years later, their family home and other areas of West Long Beach, like a corner market where Fred originally found his 1941 Willy’s truck.

Expanding the story are interviews with motorsports artist Kenny Youngblood and lauded Top Fuel dragster R.J. Trotter who help paint a more colorful picture of what Lions Drag Strip was like: the energy, the community and, of course, the cars.

“You’d see all kind of configurations on the race cars,” Youngblood said in the film. “You never knew what was gonna show up on a Saturday night at Lions. You might see a twin-engine car. You might see them line up side-by-side, you might see a three-engine car, you might see an airplane engine car, you might see turbine jet cars—all kinds of machinery.”

Though the film doesn’t dive as deeply into the cultural significance or challenges of the minority experience within drag racing—despite its stars proving that there was diverse representation in the White and male-dominated sport—”Mexican Express” makes up for some of this with the insight of local historian Claudine Burnett, who sheds light on some of the socio-political and racial makeup of West Long Beach during that period.

And for the non-enthusiast viewer, “Mexican Express” may feel slow in some places, but despite the drag in momentum, it’s certainly a worthy watch that speaks to the universal experiences of passion, brotherhood and dedication. And, of course, the sweet, sweet rides.

“Mexican Express” can be streamed on Amazon Prime, click here.