Photo by Steve Baker.

The appeals process will go forward, but for Kathy Windom, the life sentences handed to Norvin Dizadre and Emmanuel Walker last week for the murder of her son, Steven Brown, brings some closure.

But the question still nags her: Why was the Long Beach Police Department working with someone like Emmanuel Walker?

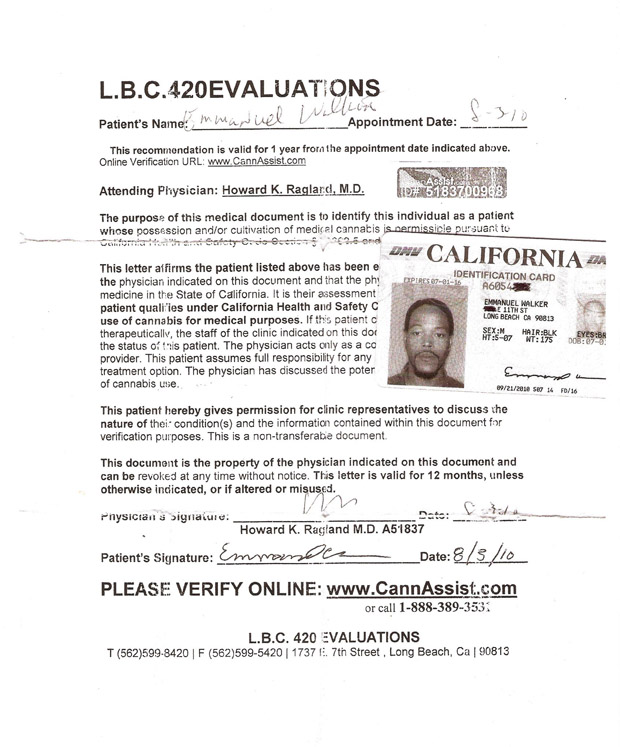

At the time of Brown’s murder, Walker was widely believed to be an aid to the LBPD in its efforts to conduct enforcement actions against medical-marijuana dispensaries. Allegedly, the LBPD had Walker join multiple collectives[1] and attempt to purchase marijuana, then police used those facts and information obtained to take action against dispensaries.

Windom says she learned of the LBPD’s association with Walker in January as she walked in a courthouse hallway during Walker’s murder trial.

“All I heard was [the question of Walker’s being] a paid informant, and I heard, ‘Yes,'” Windom recalls. “And I just lost it.”

The revelation prompted Windom to compose a letter to Chief Jim McDonnell. “It came to my attention that my son’s main assailant[,] one Emmanuel Walker[,] was at the time of my son’s death in the employ of the Long Beach Police Department[,] and that he was working as a Reliable Confidential Informant for a Detective Strohman,” she wrote. “[…] I want to believe that the Police Department and the Long Beach City Court System is on the side of getting my son and I the justice that I am demanding[;] but I am finding it hard to believe that I will get Steven’s life and his death the proper respect that he deserves if facts such as these are kept hidden and secret from me and our case.”

Windom says that within days she received a call from Commander Joe Stilinovich, who confirmed that Walker had indeed been working for the LBPD.

“[Stilinovich] admitted that they used him,” Windom says. “And I said, ‘Is he getting special attention?’ He said, ‘No. Anything like this, and we wash our hands of him.’ […] I asked, ‘Was he a paid informant?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ […] And then he said he wasn’t going to comment on anything else.”

Stilinovich and the LBPD declined to comment for this article. However, the L.A. County District Attorney’s Office verifies Walker’s collaboration with the LBPD.

“We were notified that the defendant was a paid civilian assistant of the Long Beach PD,” said D.A. spokesperson Sandi Gibbons. “The information was contained in police reports we reviewed.”

According to the sentencing memo prepared by the District Attorney’s Office, Walker had “no prior record, or an insignificant record of criminal conduct, considering the recency and frequency of crimes.” And there is no evidence suggesting Brown’s murder had anything to do with Walker’s work for the LBPD.

Nonetheless, Windom feels police showed poor judgment—perhaps clouded by the department’s zealousness in “shutting these places down so nobody won’t get their buzz or have pain [relief] from their cancer”—in choosing to work with someone like Walker.

“I don’t know who this Emmanuel Walker is, but just looking at him in that courtroom, he has a hair-trigger temper,” Windom says. “How can the police use this type of person to go out and do what he was doing? […] This guy had a temper, and I know they knew that. I know they seen that. […] I know they knew his attitude. As quick as he coulda got mad, anybody could have gotten hurt. He could’ve went into one of those dispensaries, and they could have told him he couldn’t get no weed, and he [might have] went off.”

(Walker was invited to comment for this story through his defense attorney, Javier Ramirez.)

Windom understands that answers will not bring her son back to her, but she just hopes the police will answer a mother’s questions about why they were working with someone who would be capable of stomping her son to death.

“I just want them to answer truthfully,” she says. “Did they get him out of jail to do this? Did they catch him doing something and said he wouldn’t have to go to jail if they worked with him? […] Tell the truth about why they used this person. […] If this person committed a crime but was let off to help them, come on now, my son would have been here a little bit longer. […] I just want answers. I just want answers.”

—Second photo: Copy of Emmanuel Walker’s doctor’s recommendation for medical marijuana on file at one of the collectives to which he belonged.