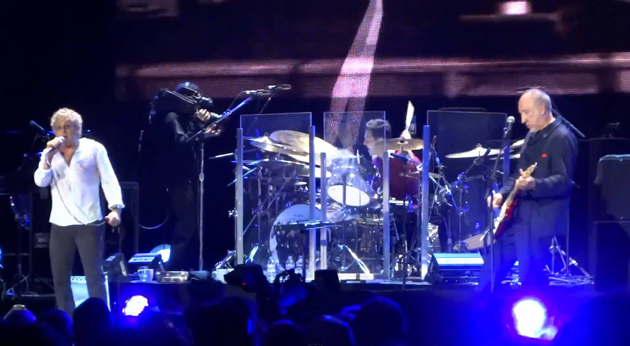

Drummer Scott Devours just completed a sold out European tour of Quadrophenia with The Who. In Part 1 of my conversation with him, he shared the story of his early years in Maryland, the rise and fall of the band, Speaker, and his roll in creating the underground music venue, The Space. In Part 2, he spoke about the importance of working with Rich Mouser, his time with Oleander and IMA Robot, and how a one-off gig with a cover band landed him the job of touring with rock legend Roger Daltry. In Part 3, he talks about his gig with Roger, the fateful call to fill in for Zak Starkey, and the unbelievable scramble to prepare for that opportunity.

Scott: I think the reason I was so caught off-guard wasn’t just because it was such a big opportunity, and I wanted it so bad. Everybody who auditioned wanted it bad. I’m just one of a large number of people. Odds were very much not in my favor. But it was because Roger quit so early with me that I’m like, “I’m screwed.” Two songs. He had me learn seventeen and he wants to hear two? Clearly, I’m not as good as I thought I was. So I was just totally convinced.

“I gotta call my family again. I didn’t get it. Boo hoo.” I auditioned for Beck, didn’t get that. Lots of near misses, you know. Big disappointments. So I was all prepared to call my family and like, “I didn’t get it.”

But that’s what Frank [Simes] said, when he finally convinced me that I had it. I was like, “Yeah, but he didn’t even want to play with me.” He’s like, “That’s because he knew right away you were the guy. He made that decision the second you played Johnny Cash with him. ‘That’s the guy. I don’t need to hear anybody else.’ He just went through the motions because everybody else was booked and he didn’t want to be a dick, and he heard a lot of fantastic drummers but something clicked, and he just…That’s why he didn’t want to play anymore. He was like, ‘He’s the guy. Done.’ He immediately said, ‘That’s the guy, no doubt.'”

So I was just, “Holy shit, it happened. It fucking happened.” And I got to call my family and it was the call that got everybody crying. Finally, there was some good news, you know, ten, fifteen years of, “Well, we got dropped,” or “Our single didn’t go to radio.” It was just disappointing. You know how a musician’s life is. A bunch of near-misses. You just aim and you miss. That’s just how it is.

So this was the one call that was, “Hey, things are going to be great.” The tour was going to be the biggest tour of my life, and it was someone that they knew. That was the game-changer. “We know who that is; the guy who twirls the microphone.” Although my mom still thinks it is Daughtry. I think, for the first month, she was like, “Yeah, my son’s playing with a guy from American Idol – Daughtry.” I’m like, “No. No. Not Daughtry.” “I said, Daltrey.” “No, you said…okay.” A little comedy in all of it.

Sander: After you processed that you actually got the gig, it must have been quite a process between where you were and actually walking out onto a stage. There must have been extensive rehearsals and all kinds of other things involved in bringing that to fruition. What was that like?

Scott: It was remarkably less than I thought, and a lot less than most people think of. The Who, in general, and definitely Roger… that’s part of the Who mentality. There really isn’t that much rehearsal. We blocked off time and we went up there every day for a week, but they don’t burn out. They just get up there and do it. I don’t know if I’m saying it right, but that’s their mentality.

You look at that early footage: They’re just fearless. Hendrix was before them and they were like, “We don’t give a shit. Fuck it. Just get up there and just blaze.” They’re absolutely fearless. They approach everything, just pound into it. So that’s how I played, at the time, certainly still try to play and that’s how I approach that music and I think that’s why Roger and I got a long so well. You don’t worry about it. You don’t think about making mistakes. You’re going to make mistakes. The Who made all sorts of mistakes. Nothing was ever the same way twice. I just played shows with them, Pete was in the wrong key and he didn’t give a shit. It’s Pete. Who cares?

Sander: I went to see them at the Coliseum in LA in 1981, right after Kenny Jones had taken over for Keith Moon, and one of the things that really surprised me was how much they stretched out in their songs. They have these three minute songs that they would stretch out and just tear it up and jam, and I never really thought of them in that context until I’d seen them actually do it. It was sort of amazing, how they would just go off. Are they still doing that now?

Scott: Oh, yeah, but in the Roger gig there wasn’t that much of that. We weren’t playing everything as The Who. He definitely didn’t want us to sound like a Who cover band at all. But there was only a certain amount of exploration. That exploration originates, in my opinion, with Pete. Pete is absolutely the captain of the ship. Then you can go to the Moonie time, Moonie and Entwistle, you know, Pete would head the ship and steer it in one direction, and then Keith would go, “Oh, okay,” and then he would take it this direction, and Entwistle would pick up on that and move it back to this.

I don’t want to comment too much on ‘back then.’ When you see the footage, you see what you see, but Zak [Starkey], definitely on this last tour… I played six shows, and then I was there on the rest of the tour just as a back-up, just in case his arms flared up. So I got to watch them every night, front row, watch how they interact. It was mind-blowing. It’s the most pure, direct influence where one musician, all the musicians, but the drummer especially is just playing off of every whim that Pete feels like playing. And it doesn’t matter what he does, where he goes. He can just stop the song right in the middle, and he will. If he wants to do it, that’s where you go. If he wants to change the key, if he wants to do a twenty-minute solo, he just does it. And Zak is an absolute genius at reading his body language, predicting where he’s going to go. Those are incredibly huge shoes to fill. Almost impossible. I mean, he’s his own artist.

In stepping into that position, and you’re sort of learning on the fly in developing that rapport on the fly, and especially if you’re not going to have a whole bunch of time to rehearse before hand. They probably don’t need to rehearse. They know the stuff backwards and forwards. They could probably play it in their sleep.

The catch is, from all the management, Pete’s never shown up for a sound check. This tour is the first one where he’s ever shown up for sound. He used to refuse to sound check. He’d just walk on stage and play. That’s Pete. They were like, “You guys should feel honored that he even cares to show up for sound check.” I’m like, “I do, because I need it. I can use all the help I can get.”

Sander: Do you feel you can develop that rapport? Obviously, you’re a talented musician, and you’re used to listening and paying attention to whomever it is your playing with, but what has that learning curve been like for you?

Scott: It was a really incredibly tough, the toughest experience of my life, times a thousand, because with Rog, we never touched Quadrophenia. Quadrophenia is what the Who are touring on, and were touring on when I got the call. So when I was with Rog, we focused one hundred percent on Tommy. We played The Real Me a handful of times. That’s one song off Quadrophenia. There’s fifteen others. They’re anthemically long and crazy live.

So when I got the call, not to get heavy at all, but it was days after my dad passed, and I was home taking care of and being with my family. So I was out of it. You can just imagine, you know, what those experiences are like. Everything’s secondary. I didn’t care about music. I hadn’t touched a pair of drum sticks. Hadn’t listened to music.

Had that not been the case, maybe I would’ve been brushing up on Quadrophenia or spending time like just because I love it. But I had never taken a critical ear to it. I never had a reason to play it live. Never had an inkling that I would. As a matter of fact, I was certain, “Well Zak’s their drummer. Clearly, I’m not going to be playing it.”

The truth is that it was almost too difficult to listen to. And then, if you pile on top of that the emotions involved in losing your parent and under really awful circumstances… I did try to listen to Quad a couple of times but it just hurt. That’s just the truth. I couldn’t get through it. I’d get through maybe a couple of seconds of I Am The Sea and got emotional. I’m like, “I can’t do this right now.” But I felt safe. I’m like, “There’s no reason to stress over that. I’m not their drummer. They have one of the greatest drummers in the world.”

So, when I got that call on a Tuesday that, “Hey, can you come down to San Diego and play Quadrophenia in front of twenty thousand people,” I’m like, “What?” The only way it could happen, and I was a little embarrassed by this, but I had to spend hours on the way down there making notes, and I mean notes of every conceivable note. Not musical notes, but notes that I could read; script that only I understood. Like this many beats, add two beats, add two beats here. Four-four here but it’s six-eight here. Solo, wait for beat, you know? It was fifteen sheets of me just scribbling through furiously and sloppily, and I finished the notes.

I was way late. I was so late that everybody was so stressed when I got down there, and for good reason, too. But they really didn’t know what they were putting on my shoulders. They just knew they needed someone to bail them out, or cancel the show, and there’s billions of dollars at stake. And their fans, they don’t want to let their fans down.

So I get down there, and I was fully dependent on notes for those six shows. I was embarrassed to admit that. It’s not like I walked up to Pete and said, “You know I can’t watch you as much as I want to because I’m staring at my notes. It was clearly apparent because, when he’d look at me, I was doing this [staring down] a lot because I’m trying not to lose my place and miss a million cues that I don’t have memorized. Plus, the live versions are completely different that the studio versions. They’re not even the same animal. And I got the live recording two hours before the show. Two hours before sound check. It was a nearly-impossible scenario. I’m still buzzing over that experience.

Sander: Have you had a chance to go back and listen to any of those shows?

Scott: I actually did get copies of the recordings, but I haven’t been able to listen to the first day, even though they said it was great. I think they think it was great because the expectations were very low. When I first pulled up, they had wanted sound check at like two o’clock. I think I pulled up at 5:30.

Sander: When was the show? At 8:00?

Scott: Eight o’clock sharp. And you know, [the show] is an hour and a half, hour and three quarters. Just Quadrophenia, live, is that long. I walk in. Pete’s on stage. I can see everybody’s expression. Roger’s all… [scowls] The managers are looking at their watches. I’m trying not to let that make me even more nervous than I already am. And I walk on stage and I sit behind Zak’s enormous kit. It is the largest, not the most things but the largest crashes, 24”, and the double-kick and toms all around. Everything’s a mile away, and I’m just like, “Agh.” There’s no high-hat. I’m like, “How am I going to play this thing?”

Before I know it, to my right, is Pete. And he’s just sitting right next to me and I was like, “Oh. Hi, Mr. Townshend.” In my mind I’m thinking that. He was so wonderful. It was the most amazing conversation of my life. I’ll never forget.

He just very calmly just looked me in the eye, and he’s just like, “Let’s talk, before you worry about any of this. Let’s just—Just talk to me for a second.” I’m like, “Sure.” And he pulled no punches, man. He said it like it is, and I love him for that. I think I played the way I played because of the way he talked to me. I would’ve been nervous had he not been.

He said something to the effect of, “You are walking into a really difficult situation. I don’t know if you have heard the way Zak and I play together.” I’m like, “Oh, yes, I have.” He’s like, “Well, we have a very special connection. We play off of each other very well, and we’ve been doing it for a long time. And that’s what you’re up against. You’re filling those shoes. That’s asking an incredible amount of anybody, and we’re asking that of you.

“This tour is going better than we ever expected. We’re getting rave reviews, sold-out shows most of the places. We have a lot at stake. If you think we’re asking too much of you, if you don’t feel that you can play up to that level, you don’t have to. I’ll cancel the show right now, and it’s no skin off your back. We’ll even pay you for today just for coming down. But I need you to tell me whether or not you feel up to it because only you know that.”

It was so earnest, so direct. No bullshit whatsoever, and he wasn’t being condescending at all. Like, “I don’t know if you’re good enough to handle it.” It wasn’t like that. He was saying it like it is. I had passed the Who fans lined up outside, with the doors delayed because of me. I walked past them. I know what’s at stake. I want to be in the audience. So, he was so honest and earnest with me, I felt totally obligated, to not exaggerate, and certainly not to lie.

So I just spoke very matter-of-factly to him, looked him right in the eye and said, “I know. Everything you’re saying, I’m aware of, and you’re absolutely right. The chemistry with Zak is beyond special. There is no other chemistry like it in the music industry. And honestly, even some of the best drummers in the world, asking them to come in on a moment’s notice and duplicate that might be asking too much. There are a handful of people on the planet that could probably do that, and I’m not egotistical enough to say that I’m going to be able to do that.

“I honestly think that’s the wrong question to ask. I think it’s unfair for you to have to ask it. It’s also unfair for it to be asked of me. Of course, I’m not going to play like Zak. Nobody but Zak is going to play like Zak. It’s like filling Moonie’s shoes. Nobody’s Moonie. But if you change the question to ‘do you want to save the show,’ I feel pretty confident that, with the notes I’ve taken, and if everybody’s really visual about how they cue me, I can get through the show. If you want to save the show, if you don’t want to cancel on all the fans, and you just want to get through it to save it, I think that’s feasible, and I think I can do a good job.

“But me having to make the call as to whether or not to cancel the show: That’s not my call. That’s your call. If the expectation is no less than Zak, what Zak brings to the table, then if you want to cancel the show, I totally understand. I respect that. But if you want to just have some fun and just go for it, I think it could be a fun night.”

And he just kind of put his hand on my hand with a kind of a sullen expression, and said, “Okay. Thank you for your honesty,” and he walked off slowly. And as soon as he walked away and put his back to me I was like, “I just gave away The Who.” I thought it was over right then. When he walked away so slowly, I thought he was going to the manager and be like, “Yeah, pull the plug. This is not happening.”

So I sat there behind Zak’s kit and I looked at that giant arena with most of The Who members up there, and Roger’s right there. I just remember I grabbed his sticks and I was like, “Well, this is as close as I ever get to playing with The Who. I’ll take it. Absorb this, man. Never forget this feeling. Even this is an honor. Just being asked and failing. I know tons of people who would give anything just for that shot, and I just got that shot, even if I didn’t get it. Just remember this moment.”

Then, Pete put on his guitar, and he’s like, “Alright, let’s do it.” And I was like, “What did he say?” I didn’t have my ears in, I didn’t have the kit ready, I didn’t have my high-hat up, I didn’t have my sticks out. He’s like, “Yeah, let’s run through it real quick.” I’m like, “But, but wait.” And I just threw my ears in my thing, turned on the video and turned on the lights, I put my high-hat up sideways, and I just played the kit as it was. And one, two, three, Quadrophenia, go.

We just ran through it one time, start-to-finish. And about three songs in, I think, my buddy, who drove me down, he says that he started seeing facial expressions change from worry to like, “Hmm, we might be able to get through this fucking thing.” And then by the end, he said everyone was smiling and starting to think, “Holy crap. Let’s go do the show.” We finished and Pete said, “Alright, we’re on.” I went back stage. Maybe forty minutes later, maybe an hour, and their like, “Let’s go play Quadrophenia,” and we did it.

Scott played six shows with The Who while Zak Starkey let himself heal. After that, Zak finished the U.S. tour.

Scott: For him to not be able to play, it’s obviously got to be an excruciatingly painful thing. I mean, I’ve had tendinitis my whole life, but it never gotten to the point where I can’t play. So, for him not to want to do what he was born to do, it’s got to be incredibly difficult, and I take that into consideration whenever I’m feeling stoked about having any of this as an opportunity. It’s at his misfortune.

Sander: Because drumming is so intrinsically physical, and because it’s like any other kind of athletic effort, there’s always a risk of injury. How do you manage that?

Scott: Not very well. I’m the klutziest person in the world. I take pre-tour behavior very, very seriously. I used to do an inordinate amount of work-out. I’d do jogging with small weights to build up a little bit of agility, a little bit of power; a resilience. But the older I get and the more punishment certain parts of my body takes, I have to be really careful not to over-do it, because I could end up in a situation like Zak, where it gets so problematic that I can’t play.

The amount of intensity playing with The Who is peddle to the floor for almost three hours. For me, it is the most difficult drumming gig imaginable. Be careful what you wish for. No chill moment. When you come in Moonie, you come in and you go and go and go until he wants to stop. You can’t just phone it in, you know?

But my problem has been, my whole career, it might be psychosomatic, I don’t know if that’s the right term but anybody who knows me knows I’m the biggest klutz in the world. I always injure myself before a tour. Never once have I set out to do what I’m considering a big tour, to thousands of people or lots at stake, Roger tour, many Roger tours, and I’ll be super- careful. I’ll be watching when I step off a curb or getting out of the bathtub, whatever it is I’m always careful.

And right before I go on tour, I mean I nearly destroy myself every time without fail, and each time it happens, I’m like, “I did it again.” I’ll snap the tendon in my knee on the Tommy tour, like the day before the gear shift, I fell off a big case. It felt like I ripped my knee to pieces. And I couldn’t stand for like a day, but for some reason when I got behind the kit, I’m like, “Well, that doesn’t hurt. I can’t walk out to the kit by myself, but get me behind the drums and I’m fine.”

Sander: Well, that’s not going to happen this time. You’re over that.

Scott: I think you’re right, although last Thursday I was marking my drum kit, you know, you tape around so you know where to put things, and I was using a cutter, and I literally almost cut off the tip of my finger. It was just Pshshsh! Blood spraying everywhere, and I’m like, “Are you shitting me?” I couldn’t play full-bore for like a week. I’m like, “Every time.” And the whole time I was doing it I was like, “Alright, this is a razor blade. Be careful. Aghgh! What? Every freaking time.”

Sander: What are you doing between now and the time you actually set out on the road?

Scott: It doesn’t make sense to most people. My family, a lot of my friends don’t understand why I’m not out and about, seeing shows, or meeting them to watch games, or whatever. Because it’s sixteen hours a day, from the second I wake up, it’s something related to what you’re talking about. The drum kit is much more expansive now, so designing a drum kit that makes it easy to play… Zak’s was huge and very difficult to play. But to produce a sound similar to Moonie and Zak, you can’t with three drums. You have a much bigger kit. Bigger cymbals, more variables.

When I played Zak’s kit, it was really painful. I know why he has such tendon problems; because he’s having to over-extend every time he hits, thousand and thousands of times. After I played his kit for a few nights, back at the hotel, “Ouch, man, that hurts.” I was much more sore.

Tweaking a bigger drum kit into a smaller space becomes a matter of millimeters. I mean everything is missing the other thing, literally, by nano-increments. You move something just a hair and everything feels much better, or a hair the other way. You’re dropping sticks every time you go around the kit. So every day I’m playing Quadrophenia from start to finish on this kit, and every day I’m tweaking something else.

I’ve built drums for this. I’ve made bigger floor toms. I’ve designed cases. It’s a massive, massive amount of work, in addition to studying Quadrophenia inside and out, live or in-studio versions, and then getting away from it so you’re not memorizing things but you are memorizing vibes. You write out all the equations and then you erase them all, so you’re a blank slate but you know the foundation of where it’s going to go.

Speaking as a drummer with so many things to hit, you still want to feel fluid and you want it to feel very organic. Where I’m used to playing four drums — I weaned myself off the Kiss kit 20, 30 years ago – down to the three drums because I’m like, “Well, less is more.” You want to be able to play anything on just three drums. Now I’m like, “More is more.” I’ve got to go back to those days. But you don’t want to hurt yourself. I’m a 46 year-old guy. I can’t play like I’m sixteen anymore. So that’s exactly what I’m doing when this interview is done. I’m going to go to the hardware store and put new lugs on the drum, put in a different floor tom, replace it with a new one, play Quadrophenia all night, ice down, sleep, do it again. That’s been my life for two months.

Sander: You played those six shows with the Who, and you’ve been playing with Roger for four or five years, so you have a definite rapport and relationship with him, and have a definite familiarity with a lot of the material. When you’re talking about that rapport that you’re striving to create with Pete, when do you know? When do you know that that’s there? When do you feel that? When do you step back and go, “Oh. Okay.” Is that something that is so intangible or is that something that you’re really aware of?

Scott: Oh, I’m definitely sensitive to it, striving for it, and totally cognizant of the fact that I don’t expect it. Aim for it but, you know. When Zak came back, he couldn’t have been sweeter to me. I got to sit at caterings and chat with him for like an hour. He’s so wonderful, not to mention he’s one of my heroes, and I was lucky enough to sit in his chair. And then he’s nice to me after. He could’ve been a dick, and I would’ve been, “Whatever,” you know? He’s my hero. Who cares? But he was great.

I got to ask him—I was like, “I got to really appreciate, from the inside, what it’s like to try and play off Pete, and to try and get that back- and-forth going. How long into playing with him was it before you felt comfortable with that?” He was like, “Oh, it was like five years.” I’m like, “Five years?” He was like, “Oh, yeah, at least.” I’m like, “I’m only on my sixth gig.” I mean I’m saying this to myself. I said, “Shit, I don’t feel so bad for not being able to emulate what you’ve got in one night. Even if you’re just being nice and it took you one year, you just made me feel so much better about not really being able to be, you know, fill shoes like that so quickly. I think I’m being a little hard on myself. Or are you just being super, super nice?”

With playing off Pete, the first couple shows I played, the very first show, he was super-complimentary. The vibe was we saved the show. He couldn’t have been nicer to me on stage. He made me sound like the greatest guy in the world. As shows went on that disappeared and we were just playing, you know?

I didn’t get much interaction or reaction from him, so I asked his guys who’ve been with him forever, literally since the sixties. And they’re like, “How are you feeling about stuff?” And I’m like, “I don’t know how to feel. Is Pete bummed or is he… Do you get a vibe?” He’s like, “Did he throw his guitar at you?” I’m like, “No.” They’re like, “Then he’s fine.” I’m like, “What do you mean?” He’s like, “We’re serous. If he has a problem with you, you’ll know it. There is no gray area. He will let you know. He’s showing up to sound check. He’s in a good space. It’s not like there aren’t mistakes, but whatever. Just go up and have a good time.” And I’m like, “Okay.” That made it so much nicer and easier. It made it easier to not stress on hitting the bull’s eye every night. You aim for the stars and you miss sometimes.

Sander: And like Rich Mouser said, don’t think so much. Just be there. Be present.

Scott: Absolutely. I have to remind myself of that every day.

—

Read more: Scott Devours: From Here To The Who – Part 1.

Read more: Scott Devours: From Here To The Who – Part 2.

{mp3}sander/ScottDevours{/mp3}

Click play to listen to this interview, or download the file.