Joe Namath would probably rather not relive the Christmas he spent in Belmont Shore in 1977.

After 12 seasons of being “Broadway Joe,” superstar quarterback of the New York Jets who he led to a Super Bowl title 50 years ago, the oft-injured 34-year-old decided to come to L.A. and play for the Rams. This was big news. Though many people today may not know Namath, it is arguable that he and Muhammad Ali are the two individuals most responsible for shaping our modern view of what a professional athlete is: entertainer, provocateur, brand.

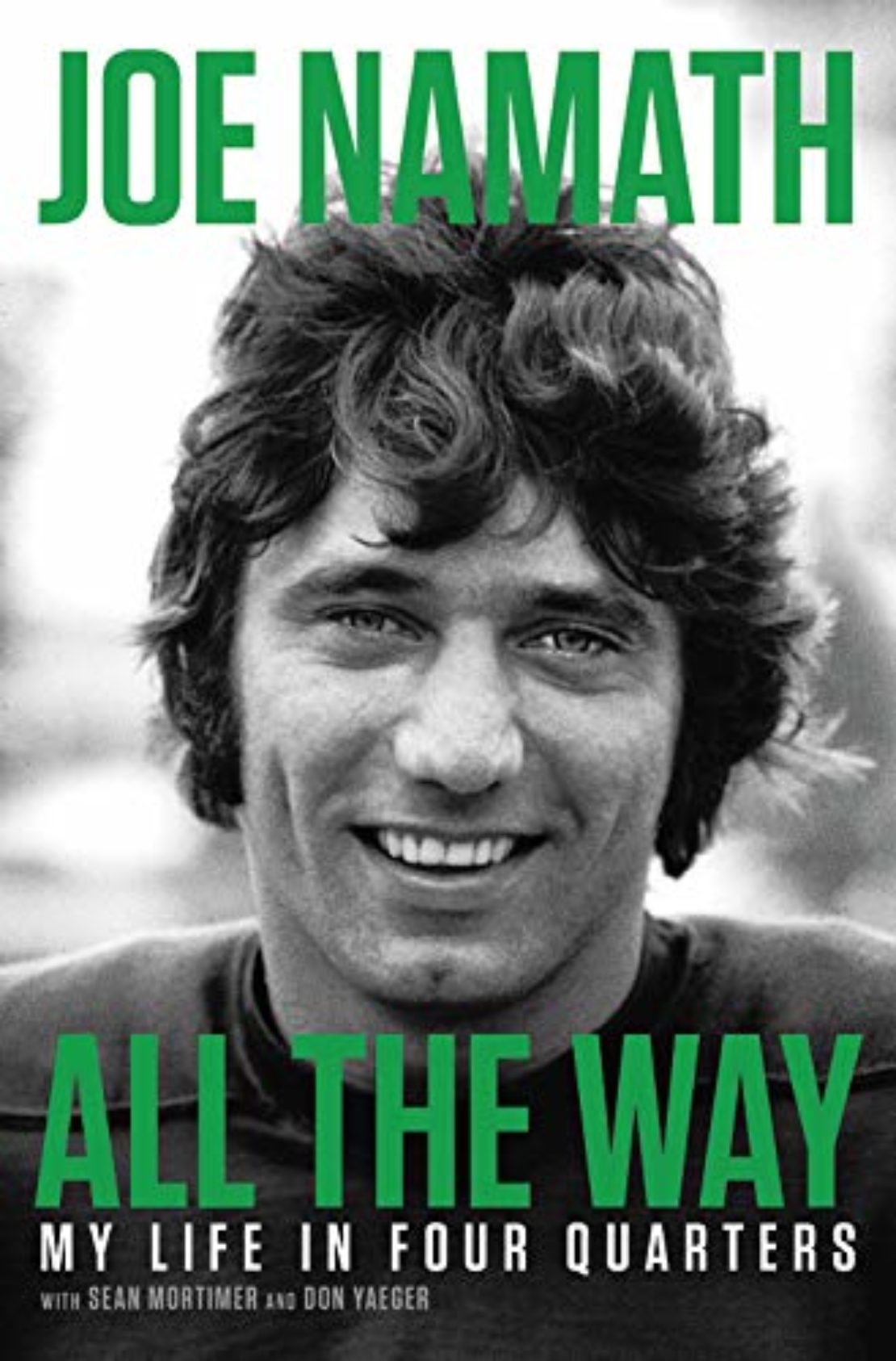

In his new autobiography: “All The Way: My Life in Four Quarters,” Namath writes that there were a lot of things to get used to about Southern California, including the air, which was so polluted, it burned his throat his first week of camp.

Though the team, in the ’70s, played in the L.A. Coliseum, they spent a majority of their time together in Long Beach, practicing at Blair Field, across the street from Wilson High School. Because of that, a lot of Rams players, Namath included, lived in Long Beach. John Morris, the Long Beach businessman who would establish Legends Sports Bar in 1979 with Rams All-Pro offensive lineman Dennis Harrah, recalls living together with Harrah, then Namath’s teammate, during the late ‘70s just a few blocks away from Namath’s rental on 59th Place. Morris’ friend, Long Beach realtor Mike Colonna, rented the place to Namath and that gave them plenty of access to hang out with him.

“Today, I’m sure people might ask: Who the hell was he?” Morris said. “In our generation, he was and always will be ‘Broadway Joe,’ with kids going crazy around him, and always so nice to everyone.”

But Namath’s kindness belied a man at a painful, quite literally, point of his life. After a dozen years of professional football—before a bevy of rules that made hitting a quarterback virtually impossible—he could no longer depend on his body to do as he wanted.

“During games, when the Rams came screaming out of the dressing room in the Coliseum they had a tradition of running the length of the field along the sideline and then breaking across the field into rows to do calisthenics. It was all I could do to keep up,” he writes in “All The Way.” “My left leg wouldn’t straighten out… I was scared I was going to fall over just trying to keep pace. I was 34 and considering my five knee surgeries, beginning to feel like a senior veteran.”

As a Ram, Namath lasted just four games. In a Week 4 Monday Night Football loss at Chicago, he was knocked out of his 140th and final NFL contest. The last pass Namath ever threw was intercepted by the Bears, though he never actually saw the interception because “I took a helmet to the chest.”

Namath was sidelined the rest of the season as his backup, Pat Haden, took over and Vince Ferragamo moved past Namath to No. 2 on the quarterback depth chart. (The Haden-Ferragamo combination would eventually lead the Rams to the 1980 Super Bowl.)

Those were the circumstances of Namath’s life during Christmas of 1977. In “All The Way” he describes it as both lonely and a key, life-changing moment to getting on with his life after football:

On a cool night at the Coliseum on Dec. 26, 1977, our Rams played the Minnesota Vikings for the division title (a playoff game). The stadium was a sloppy mess from an earlier rainfall. It was just a pile of mud between the hashmarks. The Vikings won 14-7. There was a moment in that game, man. Must have been late third or early fourth quarter, when we were behind. I was standing near Coach Knox and he turned and glanced in my direction. We made eye contact and he gave me a look, the sort that was subtly asking if I had something left in the tank for one more comeback. I didn’t give him anything back, though. We just looked into each other’s eyes, a few seconds went by, and he glanced back out to the field.

I’ve often thought about that moment.

I really feel like I let him down.

In retrospect, that was the first time I dug deep only to discover I didn’t have the confidence to compete.

The day before the game was the only time I’d ever spent Christmas alone. And boy did I ever feel alone. At around 10 at night, I decided to go for a stroll, so I walked out of my rental duplex in Belmont Shores and headed south. The back door was on the beach and I headed toward the water. Normally, I might have carried a drink with me, but for some reason, I didn’t that night. I just walked, looking around, thinking about what was happening and how everything seemed so big and empty. I didn’t see a single person. I’m walking and thinking, What am I doing?

I was all by myself and I glanced down at my flip-flops and the sand around my feet. I headed toward the jetty and climbed up on the rocks and found a place to sit. I just looked around, feeling loneliness. I was thinking about the grains of sand and the vastness above the black sky full of stars and it hit me how insignificant I was in the universe.

What was next for me? I knew I wasn’t going to play pro football anymore after this season. I was thrilled to be on the Rams and the coaches and layers and trainers were terrific guys. I can’t recall a bum on the team. The realization that I was so small and trivial in the makeup of things helped put everything into perspective.

Looking back, I’m thankful for that moment, for being alone and how that helped me connect with the greater energy out there.

Namath retired after the Minnesota loss and cashed in on his football fame with the starring role of C.C. Ryder next to Ann Margret in 1970’s regrettable “C.C. & Company” motorcycle flick. By ’78, he was starring in a TV series called “The Waverly Wonders,” as a washed-up pro basketball player turned history teacher at a Wisconsin high school. “Waverly” was NBC’s answer to CBS’ popular “White Shadow,” but lasted only nine episodes.

Looking back, John Morris said he could “visualize Joe on that peninsula, on the breakwater channel, feeling lonely because maybe everything didn’t feel real to him; I could see that.

“Maybe he didn’t have close friends or family near him. But I could also see both sides of that. I could imagine different kinds of loneliness. He got so much attention from everyone around him. Everyone gushed over him, and you’d think I was just talking about the ladies. But it was everyone. When Mike and I would be with him back at Bobby McGees, we’d go to that scene and he wasn’t bloody lonely there at all.”