The Jungle, early ’60s. Photo courtesy of the Long Beach Public Library.

Near the corner of Ocean Boulevard and Golden Avenue in downtown Long Beach is a small green space called Santa Cruz Park. It’s a “tribute park,” on the site of the original Santa Cruz Park, a dimly lit 1920’s relic where, for decades, hapless sailors would get mugged and rolled after stumbling out of a vanished downtown neighborhood called The Jungle.

“It was a real shithole to go into, and you never went in there alone,” says a veteran Long Beach cop who patrolled The Jungle, a warren of small, dark streets bordered by Magnolia Avenue on the east, Ocean Boulevard to the north, and the ocean and the Los Angeles River to the south and west.

The once-quaint little neighborhood was located right next to that epic slice of Americana, the Long Beach Pike. The Jungle’s waterfront was a U.S. Navy landing. Its 1,100 residents were mostly carnies, prostitutes, dishonorably discharged sailors, bikers, and various hustlers, along with artists and transient families taking advantage of the low rents. During this veteran cop’s tenure in the late ’50s and early ’60s, The Jungle had the highest crime rate in the city.

Even so, The Jungle is remembered fondly by some as a raw, free, and adventurous place: “It was our Venice, our North Beach,” says Long Beach native and ’62 Millikan grad Richard Chase.

The Jungle’s story echoes that of the Pike. Both started as idyllic seaside destinations and both were profoundly influenced by World War II and the establishment of Long Beach as a Navy town.

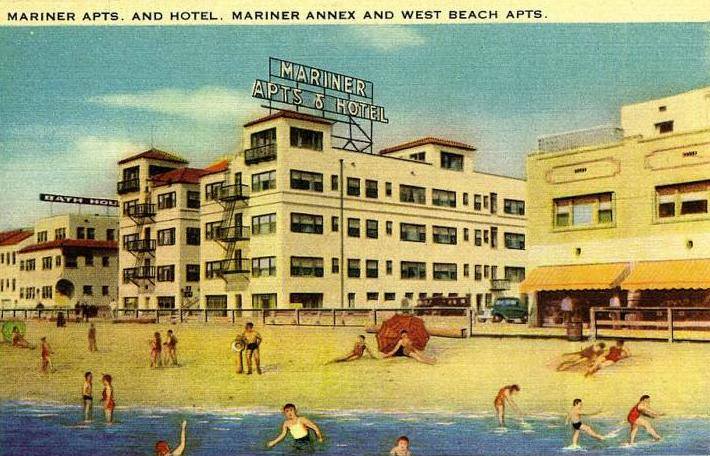

The Pike opened in 1902 and by the early ’20s had gained a reputation as the Coney Island of the West. Next to it, a new neighborhood of rental rooms, hotels and apartments with romantic sea-going street names like Neptune Place and Mermaid Place was becoming a popular summer destination. A block from the terminus of one of the Pacific Electric Red Car trolley lines, the new neighborhood and the Pike received visitors from all over L.A. and Orange County.

Pre-Jungle: Seaside destination, late ’20s.

In the late ’30s, the Navy presence began to increase, and the Pike’s wholesome, carnival-midway aura began to give way to something much darker and edgier. Tattoo parlors opened in the Pike and in the neighborhood next door. “Ship sailors” were notorious hell-raisers compared to their “base sailor” brethren, and they attracted people willing to service their needs. Throughout the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, the once-cheery oceanfront neighborhood west of the Pike broke increasingly bad.

“A sailor on liberty from the USS Helena complained that a man and a girl he met in a bar beat and robbed him of cash and traveler’s checks after luring him to an apartment on Neptune Place,” reads a 1958 police report typical of the scores of crimes reported that year in the neighborhood that had become known as The Jungle.

Local residents who were in high school back then talk of cruising through the poorly lit streets of The Jungle, glancing down “Whore Alley,” vowing to get a tattoo or maybe sneak into what must have been the ultimate Long Beach dive bar, Top’s Neptune Lounge. A few, like Richard Chase, delved a little deeper, intrigued by The Jungle’s mysterious, sinful allure.

Chase and his friends hung out and partied on the periphery of The Jungle and developed an empathy for its residents, even as they knew instinctively not to go too far into the rough and forbidding little neighborhood. “I saw some rode-hard people that had lives and maybe their lives were harder than most,” says Chase. “I look back on them with compassion.”

Former Pike employees speak of the many “painted ladies,” “floozies,” and “professional women from 16 to 60” who plied their trade at the Pike. Next door, The Jungle became known as a red light district: A police reporter from the early ’60s wrote of the “hamburger queens,” prostitutes on the streets of The Jungle whose favors could be obtained for the same price as a burger.

Photo by Richard Warren

It was in the early ’60s that certain City powers began looking to clear The Jungle.

In 1961, the Long Beach Redevelopment Agency was formed and The Jungle became its first order of business. A vision was formulated to eliminate the “blight” of The Jungle and replace it with high-rise offices and residences. Shortly thereafter, the Press-Telegram published a handful of stories about The Jungle as told by 18-year-old Jeri Nunn, a former Jungle resident who ended up helping the police arrest several of her old neighbors.

“Why do I call it The Jungle? Everyone calls it that,” said Nunn. “What else could you call it? Most of the people there live like animals.”

The doomed Jungle continued to be a haven for the outlaws and the down-and-outs until it was razed in the early ’70s. The Pike followed suit later that decade.

The area south of Ocean and west of Magnolia now looks exactly like the 1961 Long Beach City Council hoped it would–gleaming office buildings, well-groomed foliage, and absolutely no trace of the decrepit seaside getaway that occupied those 20 acres for 50 years.

What’s now called The Pike occupies the same spot as the old amusement park but, like the new Santa Cruz Park, it offers barely a trace of what was once there. Imagine, then, the sensory bombardment of the original Long Beach Pike, with its freak shows, carnival barkers, pickpockets and con artists; its aromas of salt-water taffy, fried shrimp baskets, popcorn and diesel fumes; the constant shots from the real .22 rifles used in the shooting galleries, and the chaos caused by the occasional drunken sailor plunging from the top of the legendary Cyclone Racer roller coaster; a place so wild and unruly, it had its own Jungle.

This is the second in an occasional series called Long Beach Noir, which tells the tales of the city’s creepy, crawly underbelly.

Read more: