In 1998, after 13 years leading the State University System of Florida, Dr. Charles B. Reed accepted the job as chancellor of the California State University (CSU) system. The move took Dr. Reed from Tallahassee to 401 Golden Shore in downtown Long Beach; headquarter of the premier, 23 campus, 450,000 student system of higher education.

The highlight of the transition would not be living in a new city and absorbing its culture, but realizing new opportunities and challenges associated with leading the largest public university in the world. While educating nearly a half million students annually, Dr. Reed also oversees 46,000 employees and a $5 billion budget. These are challenges in their own right.

But it was ultimately the CSU’s mission that sold Dr. Reed on the job. “When I looked at the students at the CSU, they reminded me of how I was as a student,” he explains. “Many of our students are first in their families to go to college, and come from working class backgrounds.” And that is exactly where Dr. Reed began, a working class town in Pennsylvania where his coal-miner father gave him perhaps the most important advice of his life: “go to college or go to the coal mines.”

Young Charles Reed chose college, and earned a football scholarship to George Washington University where he earned a B.S in Physical Education, and M.A. in Secondary Education, and an Ed.D. in Teacher Education.

In leading the CSU, it is also the sense of opportunity and the CSU’s commitment to educating people from underserved communities that pulled Dr. Reed in. Now, ten years later, the affects of his leadership are far-reaching.

Idealism aside, serving California as the CSU Chancellor is no easy feat, and with such stature and ability to affect great change comes great challenges. Dr. Reed notes that his “greatest challenges have come from ongoing budget issues and the lack of constant and appropriate funding for higher education.” Early this decade the state legislature slashed almost a half billion dollars from the CSU, an amount that was never recovered. The system is currently experiencing a proposed budget cut of almost $100 million for the 2008/2009 academic year, and will likely experience less support in 2009/2010.

My interview with Dr. Reed provided some indirect advice to the state legislature: “If we continue to chip away at public funding for higher education, we jeopardize the very investment in our state’s human capital and in the strength of the economic engine that has propelled California to a position of global leadership.” In 2008, when students organized statewide to advocate against the ever-recurring cuts to higher education, Chancellor Reed was lock-step with them. His administration and students were on the same page: Save the CSU, Invest in Higher Education.

One would think that when a large bureaucracy loses a fifth of its funding, services will certainly decrease, value will diminish, and morale across the board will take a sharp nose dive. But the ongoing budget dilemmas present a glimpse of Dr. Reed’s innovate leadership. It was best said by colleague Gary Reichard, CSU Executive Vice Chancellor, who noted that “despite almost continuous budget uncertainties in the state of California, the CSU has continued to grow in both stature and size. For this, we are all very much in Charlie Reed’s debt.”

Such growth and student success is seen in the Early Assessment Program (EAP), which provides 11th grade students with an early signal about whether they are ready for college level math and English. The CSU has historically relied heavily on remedial education to close learning gaps among incoming freshmen – an expensive task for the system and a frustrating and prolonging task for the student. Now with the EAP, fewer students have to wait until that critical first year in college to catch up. They simply take care of it before their senior year in high school. Not surprising, the EAP is now used as a model by several other states.

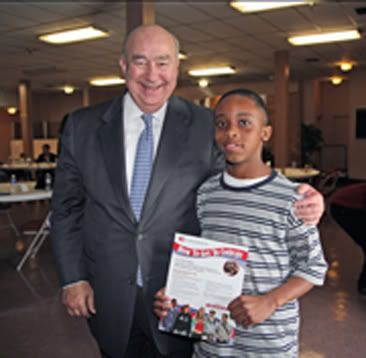

Ensuring accessibility meets Dr. Reed’s list of priorities too. In order to increase outreach to underserved communities, his leadership resulted in the “How to Get to College” poster. A simple but brilliant idea, it outlines all steps necessary for students between 6th and 12th grade to take in order to enter college. It’s clear, concise, and has been very successful. And it’s produced in five languages.

His innovation is also seen in the “Super Sunday” concept, which brings him and other CSU leaders to large African American churches to speak about a students’ road to college. As a result, the percentage of African American students has increased to 7.2% across the system.

Perhaps it’s innovative, but it’s second nature to Dr. Reed. When asked about such accomplishments, he responds that “it is critical that students from underserved communities – who represent more than two-thirds of the pipeline of students in K-12 – take the right courses to be eligible for college and have the support and resources to get there.”

Dina Cervantes, chair of the California State Student Association (CSSA) from 2007-2008, offered me some candid comments on the chancellor’s style. “Even though we didn’t agree on all issues, he always supported the presence of our voice.” In fact, Dr. Reed was pivotal in a 2001 board of trustees’ decision to write shared governance language into CSU policy. It came in the form of a resolution, and grants all stakeholders – students, faculty, and administrators – a voice in major decision making process. Ms. Cervantes insisted on taking this point a step further. In reviewing her work with California’s Intersegmental Coordinating Committee, the body that comprises leadership from the state’s three systems of higher education, Ms. Cervantes excitedly noted that the CSU delegation was the only one that included students. “That was a direct decision of the chancellor, and neither the community colleges nor the UC brought students into those discussions,” she insisted, “I was sitting at that table thanks to him.”

After interviewing Ms. Cervantes, I was reminded of Dr. Reed’s philosophy of serving the underserved, ensuring access to all, and responding to the needs of an economy that relies on qualified human capital.

All successes aside, Dr. Reed has hit snags in his ability to steer this gigantic academic ship. Ongoing labor negotiations, student concerns, and legislative incompetence have, at times, derailed his agenda and caused uneasiness among the system’s stakeholders. It is not these day to day issues that come to mind when reflecting on the last ten years, however, but that the CSU’s image is unwavering, and that it maintains a reputation of leadership and innovation in the national academic echelon.

The results speak for themselves. The CSU graduates 90,000 students into the workforce each year, and is the state’s greatest producer of bachelor’s degrees in key industries including education, life sciences, nursing, business, public administration, and engineering.

Just as we hold leaders accountable for failures, we should recognize them for accomplishments. Ten years after coming to Long Beach, Chancellor Reed’s leadership is admirable and full of accomplishments. It begs the question, which I subtly threw into our interview, “how many years do you intend to continue serving California in this capacity?”

He responds, “there is still a lot of work to do.”