Developers who want to build apartments or condos in Long Beach may soon be required to incorporate affordable units into their projects or pay into a fund that will be used to construct such housing.

The public got its first glimpse this week of a draft inclusionary housing ordinance that has been in the works for nearly three years. The Planning Commission on Thursday will hold the initial public hearing on the proposal, which is similar to policies other cities have adopted to increase their stock of affordable housing.

A big unknown until this week had been the percentage of units in each development that would have to meet the federal definition of low- and moderate-income units for renters and buyers.

In a report to the Planning Commission, staff has proposed requiring developers to eventually offer at least 12% of units to those who are low-income or moderate-income earners. The percentage would start at 5% in 2020, and increase to 12% by 2024.

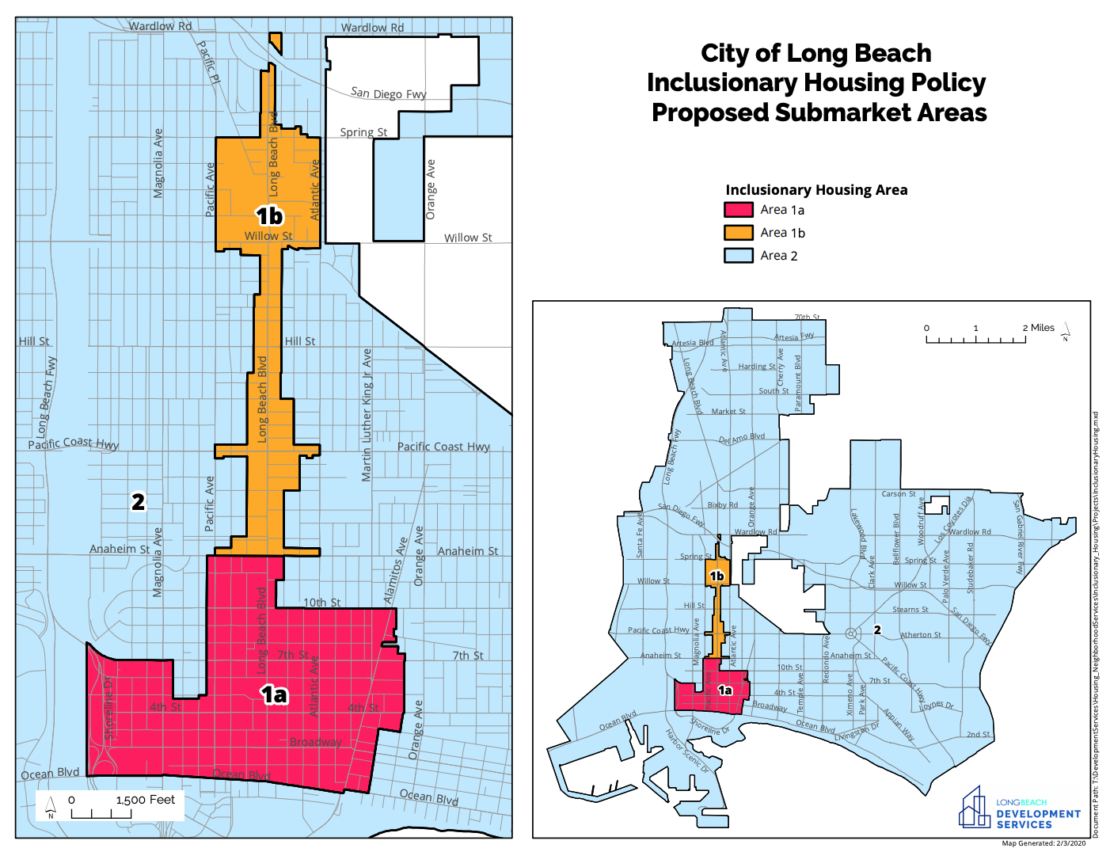

The new law would go into effect on Oct. 1 for the Downtown and Midtown areas, where construction is booming. Midtown includes a narrow stretch that runs largely along transit corridors on Long Beach Boulevard through Central Long Beach.

For all other parts of the city, where multi-unit construction is sparse, the inclusionary housing policy would phase in beginning in January 2021. The city wants time to update a bonus program that could provide incentives for developers to construct housing in these more suburban areas of the city.

The ordinance would apply only to developments of over 10 units. Of the 12% of affordable rental units, staff is recommending that half would have to meet the definition of “low-income” and half for moderate income.

For condominiums, 10% would have to be affordable for those with moderate incomes by 2024.

In some cases, developers could instead pay into a fund that would be used to build affordable housing throughout the city. The proposed amount ranges from $223,000 per moderate-income unit to $383,000 for very-low-income units.

For example, if a developer wants to build a 100-unit apartment building, they would be required to build 12 affordable units: Six of them low-income and and six moderate income units.

If certain requirements are met, a developer could opt to pay a fee instead for those units: $2.136 million in lieu of the six low-income units, and $1.338 million for the six moderate income units.

If passed at the Planning Commission level, the City Council would then deliberate and vote on the policy.

‘Time will tell’

Long Beach began crafting an inclusionary housing policy in May 2017, a few months before the state enacted a law that allowed cities to impose certain requirements on developers in response to California’s affordable housing crisis.

The requirements, however, cannot act as a restraint on development or deny developers a fair return on their investment, state law says; one of the criticisms of inclusionary housing policies is that they could cause developers to flee, worsening the housing crunch.

Mike Murchison, a lobbyist who works on behalf of developers, said in an email this week that he is hopeful the policy will not impede development in Long Beach.

“The last thing I would think that our elected officials want to see are developers passing on Long Beach opportunities because of a ‘mandatory’ policy impacting that decision,” he said. “Time will tell.”

In crafting their policy, Long Beach officials contracted with a consulting firm to study various options and conduct an economic analysis of the housing market in different areas of the city.

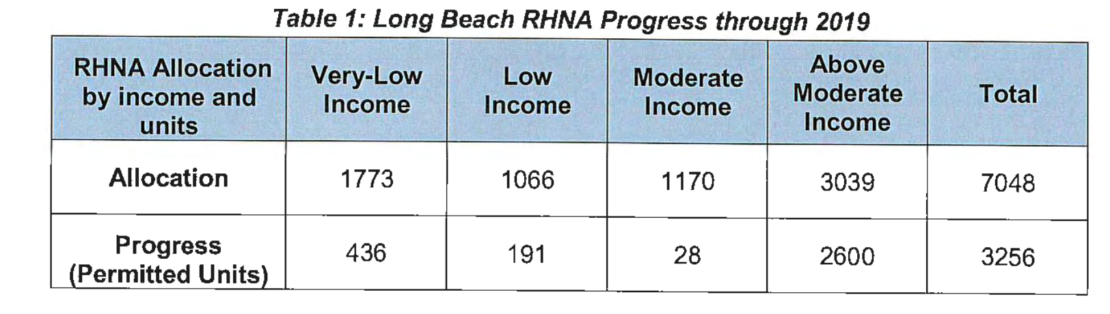

The consultants also considered state laws that require cities to contribute to the regional and statewide housing stock. Long Beach, like many other cities, is not meeting its goal.

In 2019, the city should have allowed 7,048 units of housing, but has only permitted 3,256 units.

Any policy that puts requirements on developers must take this into account, the city report says.

The report also noted that inclusionary housing policies only fulfill a small portion of the unmet need for affordable housing. Projects such as The Beacon—a 160-unit affordable housing complex—do much more to add to the housing stock for those in lower-income brackets. These projects have access to public funding sources that provide a more cost-efficient way to achieve affordability that imposing requirements on market-rate developers, the city report said.

The Planning Commission meets at 5 p.m. Thursday in Council Chambers, 411 W. Ocean Blvd.

Staff writer Brian Addison contributed to this report.