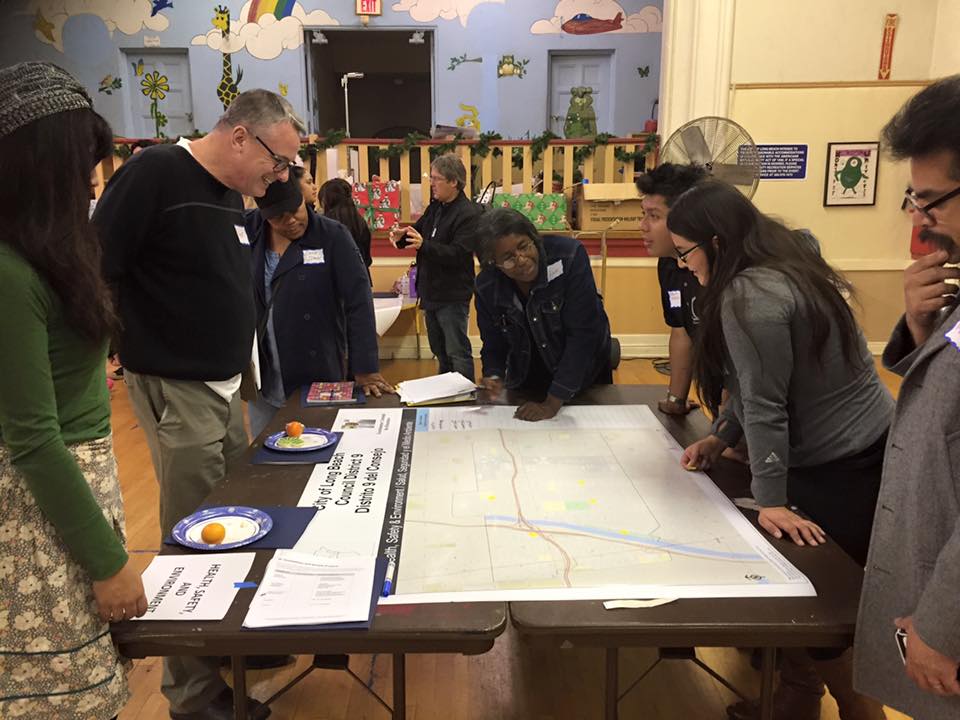

North Long Beach residents at a participatory budget training session earlier this week. Photo courtesy of Rex Richardson.

Staring through a pair of thin-rimmed glasses while picking at a short stack of pancakes, Gary Shelton launches into a description of the innards of a watch.

Like an artisan crafter of timepieces, he describes the gears, gadgets, cogs and pins, some so tiny they require a magnifying glass to see, but none less important than its neighbor. The 67-year old native of St. Louis says a watch and a government have many similarities, both requiring a level of attention to detail to fully understand what’s happening when you step back to view it from afar.

“As it’s moving, things are doing even unexpected things, but if you turn the watch over, it’s just the second hand going,” Shelton said. “But if you look at the back, it’s got all this stuff going and that’s what I like to see. When a watch breaks, it’s because a cog fell off a gear or a little screw fell loose and if you can look at it and see it, maybe you can get it fixed.”

Anyone who’s been to a Long Beach City Council meeting is probably aware that it’s often a meticulous process, with the cogs of city government churning as the minutes turn to hours. Depending on the content of the given night’s agenda, those Tuesday night meetings can often stretch into the early hours of Wednesday morning. You might also notice that a handful of people like Shelton—not wearing city employee IDs or seated on the south side of the council chambers—are on a first name-basis with the city’s elected officials.

They practice their speeches to make sure their points fit into the legally-mandated three minutes of public comment. And they do their research so that when their turn to speak comes up, their arguments are grounded in facts. Because of this, their voices seem to carry a little more weight when they make their way down the stairs to speak from the lectern.

“I hope they say ‘here comes Gary, he’s got an interesting take on something and I want to listen to see if it makes any sense,’” Shelton said.

They each have their own cause—the homeless population, neighborhood safety, environmentalism, airport noise, medical marijuana—and most come armed to the teeth with facts and city staff reports in hand. What they all have in common is they are engaged past merely showing up to a polling station to vote—something that on average of only 20 percent of the city does—and they genuinely care about Long Beach, fighting for changes to make it better.

Like a first kiss, they remember their first taste of civic engagement and how it seduced them into a career, of sorts, in activism. For Shelton, it was the demolition of the old Navy Shipyard at Terminal Island and defending Victory Park—the strip of fractured lawns that span across the businesses and condos on Ocean Boulevard—against non-permitted signage.

For Jack Smith, a former Second District resident who now resides in the same building as Shelton, it was the victorious fight that kept an electric sign off of a Walgreens.

And for Annie Greenfield, it was the meth lab in her neighborhood going up in flames, despite her many ignored calls to her then-Seventh District council member, voicing concerns of suspicious activity prior to the blaze.

“At some point, somebody needs to be accountable for this,” Greenfield said. “I became an activist. I thought—you know, if the city isn’t going to do anything, then I’m going to get up and start complaining, and I started going to some council meetings; I started a group in South Wrigley and I decided I was going to change things.”

Gary Shelton sits before Southern California Edison representatives and local officials after power outages this summer. Photo: Danielle Carson

Greenfield, who serves as the President of the Long Beach Central Area Planning Commission (CPAC), said that the key to problem solving starts with getting everyone to sit down and start a dialogue. Without those kinds of efforts to hash things out, South Wrigley might not have blocked efforts to continue predatory lending in the neighborhood. In 2006, both she and Smith were part of a nationally-recognized neighborhood improvement project for their efforts to clean up the Washington School Neighborhood. Having a plan, she said, is just as important as having an opinion.

“We don’t just whine and we don’t just complain,” Greenfield said. “We attack the problem and always have a solution. And that, I think, is what has made us very successful.”

She may have been thrust into her role as an advocate by what she said was a failure on the city’s part to fix an issue before it literally blew up, but she sharpened her skills through a city-sponsored program to educate and inspire grassroots community movements—The Neighborhood Leadership Program (NLP).

NLP is a 5-month orientation of sorts into the realm of civic engagement. It is free and open to all residents at least 18 years old. Alumni of the group include not only two former city councilmembers, Val Lerch and Dan Baker, but also hundreds of people like Greenfield, who are invested in their city and want to work to improve it. Margaret Madden, a neighborhood officer with the program, said for a city to have that kind of asset is really invaluable.

“To have a city that has all these people that want to make a difference, it’s powerful and exciting and fun,” Madden said. “There’s no price tag on having people who want to make the city better.”

Since 1992, the program has “graduated” over 630 residents from its program. It’s a cheaper alternative to the Leadership Long Beach program that has served as an almost de-facto pipeline to elected office, but also comes with a price tag of several thousand dollars. For almost all of its alumni, a seat behind the city council dais is not in the cards, which makes projects that are hyperlocal to their individual neighborhoods the focus.

Madden said just this year the Santa Fe Corridor saw multiple projects completed to help teach sustainability techniques, like composting, water use, energy efficiency and e-waste drives. They’re not projects that will have visible impacts to residents on the other side of town, but for those living in the Santa Fe Corridor, the results serve as an instant return on time invested in the community.

Community groups tabling outside the People’s State of the City earlier this year. Photo: Jason Ruiz

Other efforts by members of the city council to increase participation in local government have garnered national recognition. The city’s first, third and ninth districts have all conducted forms of participatory budgeting in the past two years, a process that allows community members to decide how to spend some of the city’s funds on community projects. It was Ninth District Councilman Rex Richardson who started that wave by making Long Beach the first Southern California city to engage its residents in that way in 2014. The turnout was a not only a success at the local level, but resulted in the largest turnout per capita in the country, with 4.9 percent of voters participating.

Richardson said it’s projects like participatory budgeting—a second round is scheduled for next year in both the Ninth and First districts—that allow for residents to feel like they’re truly part of the process. And as a council member, those projects require a certain level of loosening of the reigns for it to properly work.

“If you really value community participation, then you have to share some of your responsibilities with the community,” Richardson said. “Otherwise, it’s difficult for the community to share in the collective responsibility of making sure our community is safe, thriving. The only way to build stakeholder-ship is to meaningfully engage residents and to bring them into that shared decision-making process.”

He said over the past five years, the district has experienced an explosion in engagement, seeing its neighborhood associations multiply from about 4 or 5 to 11, not including neighborhood watch groups. This was accomplished in part by embracing grassroots efforts like knocking on doors to talk about issues instead of posting notices and tapping into community infrastructures like churches, schools and community groups. The result, Richardson said, is a more informed electorate, which makes his job both easier and harder.

“There are certainly more hands to help, but it is more challenging because you have to continue to sharpen your iron because your mettle will be tested,” Richardson said. “You can’t be afraid of it; it’s something that if you do it right, hopefully you’ve been a catalyst for long-standing change in the community.”

However, the engagement curve has not been as steep in other parts of the city.

First District Councilwoman Lena Gonzalez said the dynamics of a district can really dictate participation. She said while the issues are not confined to the First, representing a district with the challenges inherent on the Westside means a large portion of people maybe have second jobs and lack the ability or energy to make it to community meetings.

“The last thing people want to do is sit in a city council meeting after they’ve gone to work,” Gonzalez said. “It would be great to have more of that in the First District because we don’t have as much engagement as maybe other areas of the city.”

Having more people like Shelton, whose level of engagement now has Gonzalez on texting terms with him, would not only be beneficial to her district but to the city as a whole. The struggle lies in motivating people to turn out in the same numbers for less sexy presentations on topics like downtown parking and road conditions as they do for less-impactful initiatives like Meatless Mondays and the contents of vending machines.

The question of how to mobilize a youth demographic and bring them to the level of engagement of older generations is also an issue that, to date, has perplexed politicians at every level of government. Shelton, Greenfield and Smith are all retired, but have dedicated their third act to political participation. Expanding that kind of dedication to all demographics is a challenge, but engaged or not, decisions will continue to be made with or without the voices of residents.

To that point, Smith recalls his favorite gripe that he hears when out in the community. He believes in a motto that “good enough, ain’t” and that things can always be better. If you have the energy to complain about something, you just might have the energy to fix it. You may not be an elected official and you may not get credit for the end product, but you have the power to enact change.

“One of my pet-peeves are the folks that think somebody should do something,” Smith said. “‘Parking is terrible downtown; somebody should do something.’ Well, hello—you are somebody.”