Photo by Jason Ruiz.

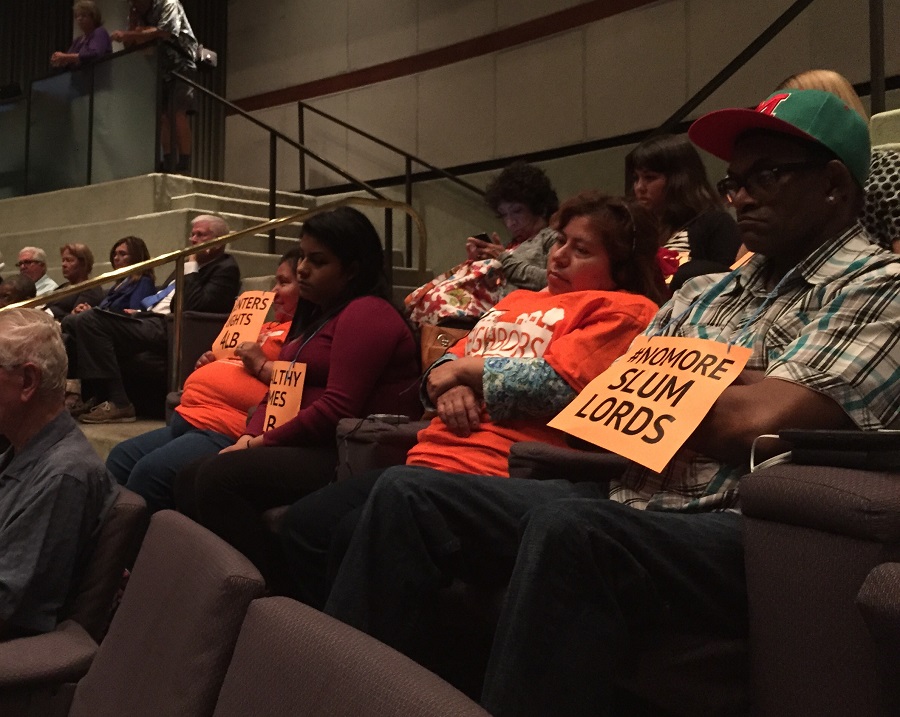

The seating section inside the Long Beach City Council chamber reflected the sharp divide on the issue that has pitted members of the apartment association against tenants in the city.

Landlords clad in suits faced off with renters holding up signs demanding stronger tenant rights in front of the council Tuesday night, as it debated the merits of the proposed proactive inspection program. The eventual vote in favor of codifying the existing inspection process and to add “baby teeth” to it was a small victory for tenant advocates, but they promised this would not be the final discussion.

Due to amendments and requests for staff to explore alternative options for data gathering and increasing fine schedules, the 9-0 vote won’t adopt the Proactive Rental Housing Inspection Program (PHRIP) into the municipal code, but will bring it back before the council for a first reading at another date.

First District Councilwoman Lena Gonzalez proposed multiple changes to the program, including the potential to publish a list of bad landlords, explore the possibility of including inspections of triplexes and duplexes and adding back elements included in city staff’s original memo that allocated $75,000 for outreach and education. The latter allocation also included implementing a California State Franchise Tax Board program for non-responsive landlords.

“There is no easy fix for a problem so enormous,” Gonzalez said. “While I support the core values of REAP, as a city we must take careful policy steps as we deal with the upcoming budget deficit. This is certainly an issue I’m committed to as long as I’m an elected official.”

The Rent Escrow Account Program cited by Gonzalez had been the resolution sought by housing advocates since the adoption of the city’s Housing Element in 2014. The program has existed in Los Angeles for over 30 years and provides tenants with the ability to withhold rent from landlords by paying it into an escrow account until habitability issues are resolved. It also provides protections from retaliation from landlords in the face of being reported for substandard conditions, by temporarily freezing rent and disallowing evictions.

New Housing Long Beach Executive Director Josh Butler applauded Gonzalez’s push to include amendments that sharpen the staff’s proposal, but recognized there still aren’t “enough tools in the toolbox” to fight back against bad landlords. Butler was optimistic that continued conversations with Gonzalez and Ninth District Councilman Rex Richardson will eventually move the group closer to its goal of a REAP-like program. Richardson pushed to include all rental units, regardless of number of units.

“I think that the measure is stronger at the end of the night than it was at the beginning, and we thank Councilwoman Gonzalez for her hard work to pass those measures through,” Butler said. “I think we have a long way to go before renters feel safe to actually report problems.”

Trust and safety were two of the biggest issues visited by the seemingly endless line of public commenters on the topic. Landlords voiced their distrust of an ordinance they feared would unfairly punish owners who have worked in good faith, while tenants said they’ve stunted the city’s proactive inspection program by not answering knocks at their doors by code enforcement for fear of retaliation by their landlords.

“I’ve been evicted four times because I’ve asked for repairs,” said 25-year Long Beach resident, Raquel Cervantes, with the help of a translator. “Everything is fine and the relationship with the managers are very good as long as one does not complain. When one asks for repairs, everything goes downhill.”

Jorge Rivera, a community organizer with Housing Long Beach, said PRHIP falls short of what renters in the city actually need, as it fails to include rental properties with less than four units and allows fear to persist in tenants because of the city’s inability to defend them when eviction notices are administered. He said this leaves tenants with the option of moving or taking the case to court.

Officials from the city’s Department of Development Services, which oversees code enforcement, said that litigation between a tenant and landlord fall outside the city’s purview.

“People are scared, people are afraid,” Rivera said. “I have a resident sitting out here who just got knocked on and she’ll tell you that her neighbors did not open the doors. Why? Because they’re too scared. It’s not that they don’t want it to be inspected, it’s that they’re scared of what’s going to happen if they do get inspected. How does this program protect them from that?”

Some members of the Apartment Association of California Southern Cities were just as impassioned in their asking council not to pursue further legislation that landlords in attendance felt is unwarranted and unfair. Meanwhile, some supported punishing those bad actors who were not in compliance and gave other landlords a bad name.

Malcolm Armstrong, who owns 24 rental units in the city, told the council to “not get into our business”, stating that most owners are ethical and take pride in presenting people with nice living quarters. He said passing a program like REAP would create a slippery slope where unmet requests would result in code enforcement being called at an alarming rate.

“You’re going to have all the bad tenants in the city calling you up, requesting lower rents and blaming landlords for the conditions we create,” Armstrong said. “There is another side to this, and I’ve been a renter for most of my life. But please don’t get into our business.”

Paul Bonner, the president of the association, backed the ordinance including the amendments posed by Gonzalez. He stated that quality rental housing was critical to the community as a whole, and that the proposed ordinance was in the best interest of the city, as long as it targeted the right people.

The council explored a way to incentivize good landlords, with Fifth District Councilwoman Stacy Mungo stating her support for a program that would allow for units without a history of non-compliance to be rolled over to a less frequent 48-month-inspection cycle. She claimed this would allow for the city to focus resources on the properties that need them most.

“Inspections should focus on slumlord properties and properties where serious code violations exist,” Bonner said. “There is no room for us to allow serious code violations. City inspectors have not turned their head the other way and we believe in a zero tolerance policy.”

However, Bonner’s comments fell short of backing the REAP program that housing advocates have pushed for, which would address the “worst of the worst” landlords. Earlier this year, an official with the Los Angeles program said that of the over 750,000 rental properties that fall into its REAP program, only 4,000 units ended up in their office’s jurisdiction, a figure representing less than one percent.

Butler took exception to the volume of comments disparaging a tougher program that would target “slumlord” owners. He said that while he doesn’t think anyone who is a part of the apartment association operates properties in these conditions, if there are, he hopes they’re expelled from that organization.

“Long Beach does not look good for having slumlords, but it looks worse for not doing anything about it,” Butler said. “It’s shocking to me that so many people are here tonight [who] don’t want to see us do anything, [who] want to let slumlords off the hook.”

The cost of implementing any program took precedence over the council’s discussion last night, as the city heads into projected years of fiscal deficit. Third District Councilwoman Suzie Price has said that regardless of the city staff’s computations—something that had come under fire from housing advocates, as they claimed an inflated budget was created to scare off support—any money being spent would have to be scrutinized.

Eighth District Councilman Al Austin, using the staff comparison’s to Los Angeles, downplayed REAP as the solution for Long Beach. Despite the staff memo citing several cities that have rent escrow programs, Austin credited Los Angeles as the only city operating one due to the expense.

“If REAP was the answer, so many other cities would be doing it,” Austin said. “It’s costly, and that’s what is giving this council great pause, and it’s certainly given me pause.”

As much of the fiscal impact was weighed, nearly all members of the council conceded that at some point the human cost had to come into play. Vice Mayor Suja Lowenthal stated that while the proposed ordinance does not incorporate a mechanism to protect against retaliation, the council shouldn’t fall into the belief they can’t do anything about it.

Seventh District Councilman Roberto Uranga took it a step further. He said he recognized that the ordinance being discussed, even with the amendments, had “baby teeth,” ones that could “fall out after the first bite,” but that the motion was the start of solidifying the city’s ability to combat bad landlords. He said the city wanted to send a message that they’re paying attention, and if landlords aren’t in compliance, it will come after them.

“It’s not perfect, what we’re dealing with today,” Uranga said. “It’s something that moves us in a positive direction. It’s not REAP, let’s face it. That’s not what we’re dealing with tonight. We want it, you want it, fine. However we can’t get there, not tonight. But at least with these amendments we’re getting somewhere that’s going to be meaningful and maybe later on down the line we move forward with this.”

The process is far from over, as city staff will now must analyze complex questions posed by the council. Such questions include what exactly is a rental unit and whether or not the city has the resources to inspect an estimated additional 15,000 units, when it currently only aims to inspect some 5,000 units annually.

The one item all parties involved appeared to agree on is that bad landlords have no place in Long Beach. How to go about policing them is a topic sure to cause continued friction between the apartment association and tenants. It will also place council members in the unenviable position of having to continue to vote against a program that seemingly could improve the lives of some of their constituents.