The physical state of Long Beach’s streets is deteriorating and requires a substantial uptick in investment for preventative maintenance to avoid spending more money on reconstruction in the future, according to a report delivered to city council Tuesday night regarding the city’s pavement management plan.

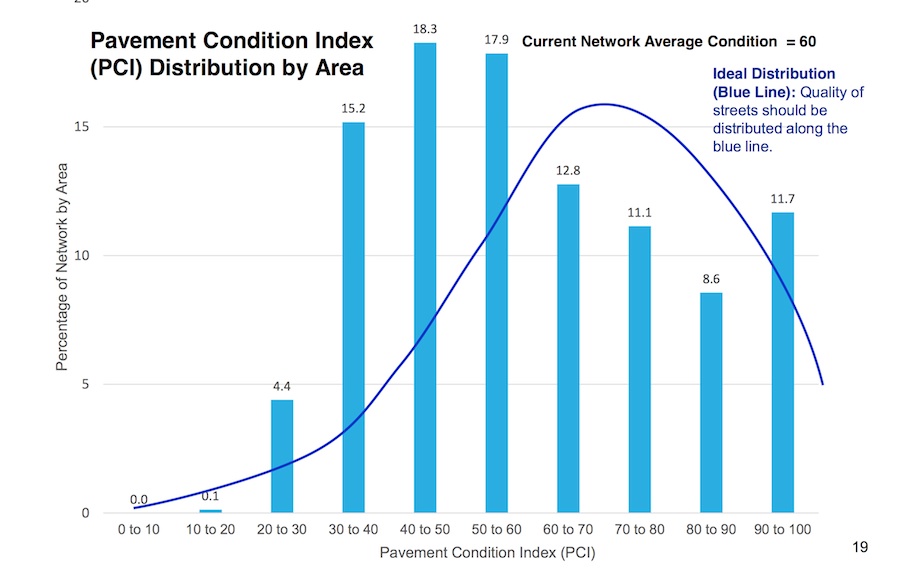

Director of Public Works Ara Maloyan laid out the daunting task before the city, as much of the nearly 800 miles of streets and roadways in Long Beach are rated as fair or good—a city wide average of 63 out of a possible 100—on the pavement condition index (PCI), which rates the relative health of road surfaces. In order to bring streets in the city back up to speed and eliminate a backlog of roads in need of repair, which currently sits at 20 percent, the city will need to spend an estimated $330 million over the next 10 years.

“Roadways form the economic backbone of a city, they provide the means for goods to be exchanged, commerce to flourish and commercial enterprises to generate prosperity,” Maloyan concluded. “The overall condition of a city’s infrastructure and transportation network is a key indicator of economic prosperity. Roadways networks in general, are one of the most important and dynamic sectors in the global economy, having not only the influence of the economic well being on a city, but a strong impact on quality of life.”

The city currently finances road repairs through a variety of avenues including state, county, federal and general funds which total an annual expenditure of $18.1 million. Although Maloyan’s report showed that the city has slightly increased its investment in streets over the past 10 years, the disappearance of one time funds from voter-passed propositions and the continuing decay of roadways has left the city with a shortfall of about $15 million annually to bring its streets back into excellent condition.

Maloyan’s breakdown of three options the city could pursue.

Maloyan displayed several courses of action that the city could take and their given impacts over a ten year period on both the average PCI and the backlog of streets in need of repairs. He compared the backlog of repairs to a maxed out credit card, stating that at a point payments only cover the interest and not the principal balance unless the payments are increased.

Being proactive in repairing streets is imperative to maintaining and improving the health of streets but also in saving the city millions of dollars down the road. On average, replacing a mile of roadway in the city costs $1.2 million, which would equal to over $940 million to replace all street surfaces in Long Beach.

According to pavement experts, a backlog of 10-15 percent is deemed manageable while those approaching 20 percent, the current backlog for the city, are considered unmanageable unless “aggressively checked” by large rehabilitation programs.

If the city maintains its current budget, about $15.3 million, the average PCI would drop to 60 and the backlog would increase by 24 percent. If the budget were adjusted to sustain the current state of the streets, which would require an added expense of nearly $6 million, the average PCI would remain static and the backlog would increase by one percent.

The most expensive option, but the most responsible according to Maloyan, would be to invest in the infrastructure of the streets, raising the average PCI to 69, reducing the backlog to 13 percent at price tag of nearly $16 million annually.

“Streets that are repaired when they are in good condition will cost less over time than streets that are allowed to deteriorate to a poor condition,” Maloyan said. “Without an adequate routine pavement maintenance program, streets require more frequent reconstruction therefore costing millions of extra dollars. One dollar deferred today means an 8 dollar cost tomorrow.”

There are several contributing factors to the declining conditions of the city’s streets. Maloyan said heavier vehicles, increased volume of traffic—some streets in the city have over 50,000 vehicles drive on them daily—and the quality of oil being used to surface the streets have resulted in roadways that don’t last as long as those laid down in previous generations.

Over 50 percent of the city’s network falls below a PCI of 60.

The city is not alone in this problem, as only two of the 58 counties (Orange and San Bernardino) in the state have a PCI above 70 according to SaveCaliforniaStreets, a group that compiles biannual reports of the state’s road conditions. The group’s 2014 report published in October showed that the statewide PCI dropped to 66, considered “at risk,” and out of all the counties, all but four have streets categorized as “at risk” or “poor.”

“To see the streets that we drive on, this only confirms the poor, marginal and fair streets that I drive on everyday and that are in our community and it’s just a disservice to taxpayers,” Mungo said. “We really need to look at our policy options,” said 5th District Councilwoman Stacy Mungo.

Third District Councilwoman Suzie Price joined the rest of the council in applauding Maloyan on his work, saying that the health of the roadways is something the council needs to turn its attention to.

“I think this is exactly where our energy and our resources as a council should be focused when we’re talking about the basic services that we provide to our residents,” Price said. “I’m glad that we’re focusing on this and more importantly, taking a broader global view of the current conditions of the streets in the city.”

Other council members raised the prospects of offering street sponsoring opportunities or allowing for residents to subsidize the cost of repairing streets that they request to be fixed. Ninth District Councilman Rex Richardson asked if additional funding from the state was in the works to which Maloyan stated there wasn’t, but city staff would apply for additional funding if it becomes available.

One thing Maloyan was adamant about in his suggestions to the council was that whichever direction the city takes in funding streets, the practice of dividing up money equally by district should be stopped, as certain parts of the city with street surfaces in advanced stages of disrepair require extra attention.

“Think of our network as a human body, if one part of the body is hurting, instead of sending all the help to that component and letting it heal, we’re dividing it by nine and only allowing one-ninth of the help to reach the part of the body that’s hurting,” Maloyan said.