The Long Beach Planning Commission on Thursday discussed recommendations for a future inclusionary housing ordinance—which could mandate that developers contribute to the city’s affordable housing stock.

The report was compiled by a Los Angeles real estate advisory firm Keyser Marston Associates and released publicly last week. It includes suggestions that Long Beach leaders—including the City Council—will mull this fall.

Inclusionary housing policies can require or incentivize developers to set aside a percentage of units that are sold below market rate. The number of affordable units is often tied to the size of the project, with larger buildings requiring more below market rate units. Developers could also opt to pay in-lieu fees to the city to avoid renting or selling units for below market prices.

The fees would be paid into a fund that the city could use to loan to affordable housing developers in the future. Cities across the country and in the region have had inclusionary housing policies in place, in some instances for decades, and Long Beach started its process of crafting its own about two years ago.

The Keyser Marston report laid out a number of options for lawmakers to consider, including the percentage of units that could be set aside for varying levels of household incomes and where those rules might apply in the city.

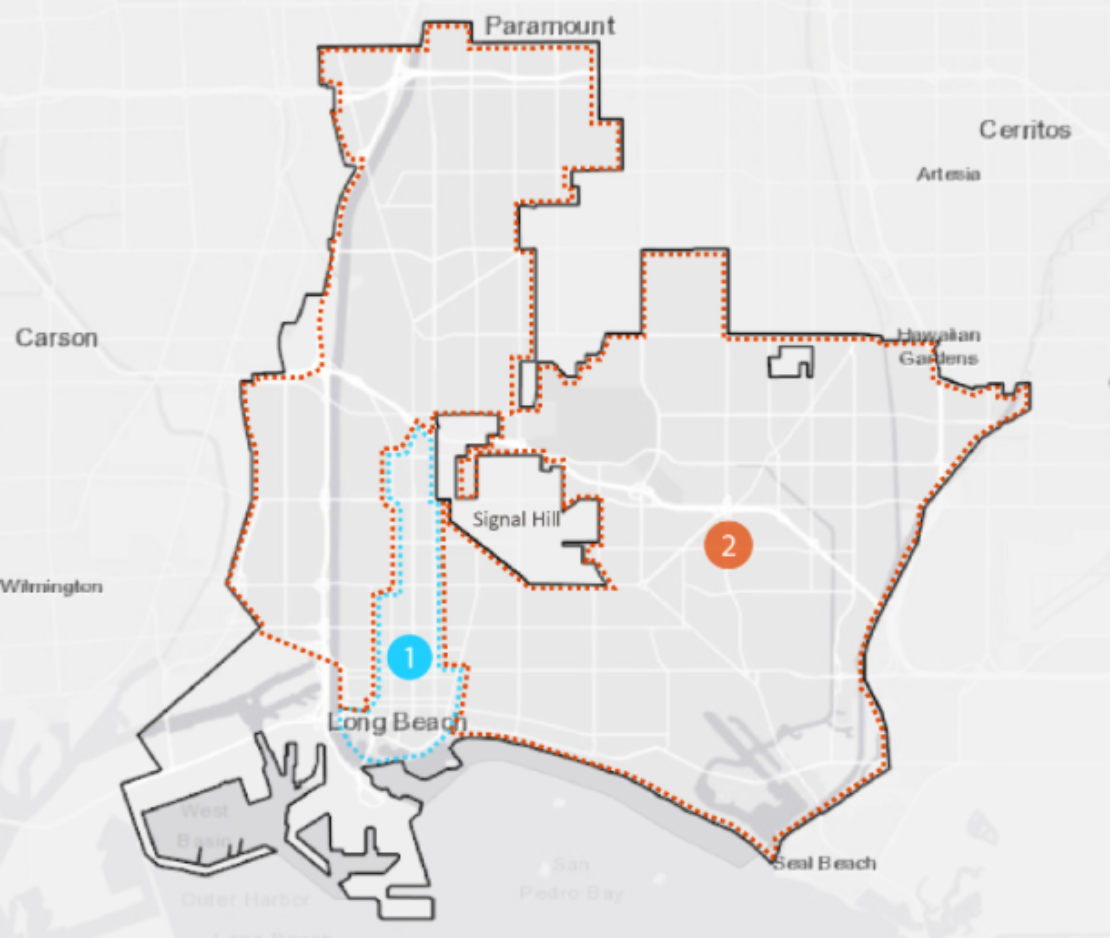

The firm divided the city into two submarkets, with one segment including Downtown and extending north to the northernmost border of Signal Hill being subject to most of the proposed requirements. That segment of the city has been the focus of intense real estate development over the past decade with over 4,000 residential units in varying stages of completion.

The region accounts for about 85% of all new residential units built in the city in the last 10 years, according to the analysis. The rest of the city, due to its recent lack of developments, would be subject to another set of rules if the report’s recommendations are adopted, including easing development standards on future projects to incentivizing future projects to have affordable housing units.

If the City Council does adopt a policy this year, Long Beach would become one of over 170 cities in the state that have done so—though the city, in the words of one planning commissioner, would be “late to the party.” City staff said it had been looking to other cities, some of which have had policies in place since the 1970s, to build a policy for Long Beach.

However, Director of Development Services Linda Tatum said that Long Beach’s version would not merely copy what other cities have in place.

“We aren’t trying to mimic what other communities are doing,” Tatum said. “Land values are different, demographics are different, but we’ll definitely be taking a closer look at cities that have had success to see what components of their programs could work.”

The city of Santa Ana has had a policy in place since 2011 that has led to the development of 33 affordable units, 23 of which are ownership units. It’s in-lieu fees have generated nearly $14 million as of the end of 2018 with its City Council allocating about $9 million of that revenue to aid in the construction of 108 additional affordable units and the creation of 200 emergency shelter beds.

San Diego requires 20% of units be set aside for affordable homes, while West Hollywood and Los Angeles mandate 15%. New York City requires 5% of units to be set aside for people experiencing homelessness, and on some city financed projects, those set asides have risen to as high as 60%, the New York Times reported in October.

The report presented to the Planning Commission Thursday night recommends setting aside 11% of homes in the Downtown core for buyers deemed “very low income,” and up to 19% for those who are moderately low income.

The in-lieu fees paid by developers could range from $223,000 per unit and $383,000 per unit depending on the project size and the income level of housing that is being forgone by the developer by paying the in-lieu fee.

However, Tatum said that the city will try and structure the fees so that the city would the use of fees in favor having developers build the units into their projects.

Developers cautioned the commission to not recommend policies that could potentially stunt the development momentum the city has been building in recent years, with some asking that ownership units be exempt from a future policy, and others suggesting that the program be voluntary for developers.

Kathe Head, a managing principal with Keyser Marston who helped prepare the report, said that inclusionary housing policies have had little discernible negative impact in cities that have already developed them and in most cases developers opted to build the units rather than pay the fee because it allowed them to exercise density bonuses.

Head said that in four cities she studied 10 years before and after they adopted inclusionary policies, development seemed to fluctuate with normal market forces and “inclusionary did not have a noticeable effect.”

While community members expressed gratitude that the city was finally taking up discussions on a policy, they advocated for stronger, citywide regulations. Many expressed dismay that the city would be carved up into two sections with one set of rules for one portion and a separate set of of rules for another.

“We want to make sure that whatever is passed doesn’t reinforce a history of racist housing policies and lifts up all of Long Beach,” said Christine Petit, executive director of Long Beach Forward, a member-group of a coalition pushing for a stronger policy to be adopted.

Petit warned that separating the city into two sections with two sets of rules could become another form of geographic housing discrimination.

Long Beach has a history of redlining neighborhoods and racial covenants, practices that were designed to keep persons of color out of certain neighborhoods by restricting loans or outright denying the sales of homes to them by law.

Others urged that every part of the city should “pull its weight” and that granting developers special privileges like expedited plan approvals and parking and set back exemptions could only hasten a ripple of displacement that has been emanating from downtown.

Susanne Browne, a senior attorney with Legal Aid Foundation Los Angeles and an advisor to the coalition of community groups, said that the city needs a citywide policy that helps the neediest of its residents.

Out of the options presented Thursday, Browne said she would favor the lower percentage of units being set aside for the lowest income brackets because they are the ones who need the most help. She said, however, that element would likely be a contentious one.

According to the report, the city needs about 5,300 units that cover moderate, low income and very low income earners. However, the very low income bracket makes up the largest chunk of unmet housing needs at over 1,500 units.

Browne said that the development in Downtown has already led to tens of thousands of displaced residents through direct and indirect displacement.

“We would be in the best position if we had had an inclusionary housing ordinance in place that required all of the Downtown developers to include affordable units in their projects,” Browne said. “That was a big part of what we were fighting for in the downtown plan campaign was inclusionary housing. We ultimately lost but we weren’t asking for in-lieu fees, we were asking for affordable units to help prevent displacement.”

“We’ve missed the boat on thousands of units developed Downtown,” she said.

A draft ordinance is expected to be brought back to the planning commission for a recommendation before it heads to the City Council for potential adoption. City officials have signaled that a vote could take place as soon as this fall.