For more than 25 years, Edward Pribonic has been the king of Queen Mary inspections.

Each month, the city-hired engineer scours the ship, snapping photos of its paint failures, busted pipes, standing water and other issues. He’s filed close to 400 inspection reports with the city of Long Beach since 1992, chronicling the iconic ship’s slow deterioration under a string of operators.

As a mechanical engineering consultant, Pribonic has long raised concerns with the city over what he says are safety issues, deferred maintenance and long-term neglect of the Queen Mary. But Pribonic offered his grimmest assessment yet in a draft report of his August inspection.

“Last month I stated that the ship has never been in a worse condition,” he wrote. “That statement is surpassed by the condition found this month which is even worse, as new failures and additional neglected areas are added to the list. Without an immediate and very significant infusion of manpower and money, the condition of the ship will likely soon be unsalvageable.”

Although Pribonic’s monthly inspection reports are publicly available, his highly critical drafts from July and August have not yet been finalized and released by the city. The Post, however, obtained copies.

City officials have acknowledged that the Queen Mary needs significant work, but they don’t always agree with Pribonic’s stronger language.

In a statement released Wednesday, the city said it is in the process of analyzing the August draft report, which “ultimately may be updated with clarifying statements received by the consultant.”

“The city is engaging with outside third-party engineers to peer review the report and others and provide additional information on the status of the ship,” the statement said.

In a recent interview, Johnny Vallejo, the city’s property services officer who oversees the Queen Mary, said he believes that Pribonic, in his passion for the ship, sometimes uses more emotionally-driven statements instead of “professional engineering language.”

“Oftentimes,” Vallejo said of Pribonic, “the engineer will admit that his language was a little hyperbole and he’ll say, ‘Well, I was trying to get your attention.'”

Vallejo said the city meets with Pribonic monthly to discuss his inspections and then uses them to guide maintenance plans. City officials have said the ship is far from unsalvageable and that significant work has been done to make it safer.

“Obviously we take his concerns very seriously,” Vallejo said. “Ed works for us, and we use his expertise to inspect the work and raise concerns. His writing style is something we’re working on.”

Pribonic, a 72-year-old former safety engineer for Disneyland who specializes in amusement park rides, has said he’s simply factually describing the conditions as they are. He said that if his language has grown stronger, it’s because the issues have grown worse.

That’s especially true under the ship’s new operator, Urban Commons, Pribonic said, declining to discuss details.

“I’ve put in over 25 years of service to ensure the proper care of the Queen Mary and I’m more concerned than ever that I’ll never see that mission accomplished,” he said.

Repairing the Queen

Urban Commons, a Los Angeles-based real estate investment and development firm, signed a 66-year lease to operate the city-owned ship in 2016. As part of the agreement, the city issued $23 million in bonds to fix some of the most critical repairs listed in a 2015 marine survey. Urban Commons is on the hook to fund the remaining repairs. The marine survey projected costs of up to $289 million for urgent repairs over the next several years, a figure Urban Commons disputes.

Many of the initial repairs went significantly over budget and the $23 million was spent before other critical projects could be addressed. Fire safety repairs, for example, were initially projected to cost $200,000, but the cost ballooned to $5.29 million to fix an outdated sprinkler system that apparently hadn’t been touched in decades.

This month, the city sent Urban Commons a letter stating that it has not met its obligations to maintain and repair the historic ship. The company, according to the letter, could be in danger of defaulting on its lease agreement to run the ship if critical repairs are not done.

In his August draft report, Pribonic detailed unfinished work and poorly completed projects. For example, the Queen’s three smokestacks, arguably the most iconic symbols of Long Beach, received fresh coats of red paint last year. But the paint on one smokestack is already peeling because it wasn’t properly applied.

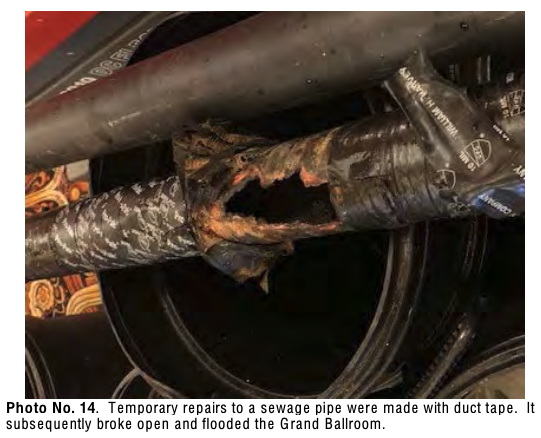

Near the Queen’s bow, the decks have been restored with historically-accurate teak wood. But wood in other areas is decayed and splintered, with no identified funding to finish the project. The reports raise particular concern over standing water in the bilges. Over the summer, the Grand Ballroom—where community groups such as the Rotary Club of Long Beach hold regular meetings—flooded with sewage after a corroded pipe wrapped with duct tape busted open.

Urban Commons Principal Taylor Woods, in a statement released to the Post earlier this month, said the company has prioritized critical projects and that repairs are ongoing.

“To date, we have completed the repair/installation of air conditioning to a number of guest rooms, addressed time-sensitive plumbing repairs, updated guest services equipment that are essential for operating and accommodating guests, and finalized several exterior paint projects,” he said. “Additional paint projects are currently underway and will be ongoing, as well as new carpet installations, teak restoration and several ADA Corrections that will be completed before the end of this year.”

“Urban Commons remains fully committed to our partnership with the City of Long Beach and our shared vision of restoring, preserving and enhancing the Queen Mary,” he added.

Pribonic said one of his biggest concerns is replacement of the ship’s 22 corroded lifeboats, a project he said he’s been pushing the city to consider for years.

A recent city memo noted that the lifeboats are at risk of falling from the ship or breaking apart. The city is working with Urban Commons to find funding for the project, which has an estimated cost of $2.3 million.

The city in its Wednesday statement said staff “continues to work collaboratively with Urban Commons to identify capital needs on the ship. In November of this year, Urban Commons is expected to present the city with a plan to address some of the ship’s more urgent repairs.”

A unique level of scrutiny

Long Beach Economic Development Director John Keisler said the ship’s conditions may seem alarming to someone scrutinizing the monthly inspection reports, but in the bigger picture, he said the city and Urban Commons had made significant headway on repairs for the Queen.

“We believe the ship is safe today and much safer now than it was three years ago when all the work was started,” he said.

Keisler said no other publicly-owned entity in the city sees this level of scrutiny with publicly-available monthly inspection reports.

“Imagine if someone was walking through your apartment and detailing everything that they see every week or month,” he said. “Yes there are significant amounts of findings, but that is what we pay for.”

He said Urban Commons has been open and transparent in its work with the city, performing beyond the requirements for a private company. He said the city is working with the company on a maintenance plan to address the most critical issues.

“It’s a very unique situation, and they have been very open to the extent that they have exceeded the requirements of the contract,” he said.

As for Pribonic’s reports, Vallejo said the city is paying attention.

“For a long time, his reports did not get the type of consideration on the ship side and city side that they are getting now,” Vallejo said.