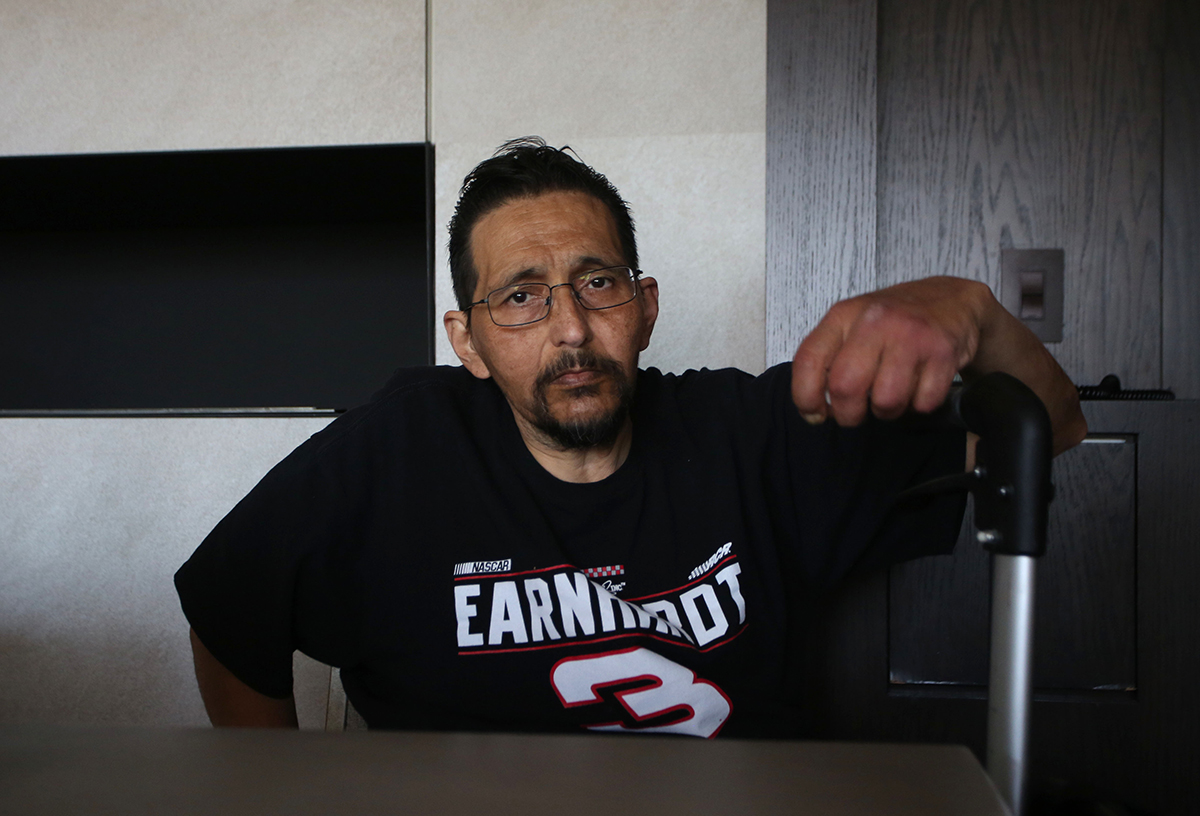

Pedro “Pete” Davalos says the four days he spent in immigration detention consisted of a dozen microwave burritos, a dozen water bottles, a metal bench, a toilet and overhead lights that never shut off.

Without a window, a shower or the insulin he needed to treat his diabetes, the 54-year-old remembers little beyond the pain. He recounts the bruises that slowly marched up his back. With no mattress or blanket, he recalls shivering while trying to sleep on the metal bench.

“My whole body was hurting,” Davalos said.

Davalos spent those days in the downtown Los Angeles federal building, which, since June, has housed hundreds of immigrants as an impromptu detention facility. Following a transfer to San Diego, he was sent to Tijuana with little hope of ever returning to the United States.

His wife, a U.S. citizen who had rushed down to receive him, described a “gray-looking” Davalos, “almost half-dead,” nearly falling out of a wheelchair given to him. With him, he had medication for a man named Javier. It was insulin, she said, but in a form he wasn’t able to take.

Fortunately, Davalos’ wife had paid for an expedited shipment of his medicine to arrive at their Long Beach home so she could drive it down to him when she received him in Mexico.

“One or two more days, he would have been dead,” she said.

“I think that’s one of the reasons why they kicked me out so quick,” Davalos said, adding that he was told his medical status meant he couldn’t be released from custody unless somebody was there to pick him up.

His family now ensures he wears a blood sugar monitor every day to alert them if his level drops above or below average.

Davalos was brought to the U.S. by his mother at 3 months old, but criminal convictions as a young man derailed his chances of ever gaining citizenship. Now, after a lifetime here, including more than a decade in North Long Beach, he’s stuck in a nation he hasn’t visited since 1988, without his immediate family, a car or a permanent address.

While speaking with a Long Beach Post reporter, Davalos was hesitant at first to tell his story with his name attached. He agreed to go on the record when he learned the federal government had already used his face and name in a press release.

Davalos, according to the Department of Homeland Security, is one of the “Worst of the Worst Criminal Illegal Aliens” it has bragged about arresting during the recent surge of immigration operations. In the press release, a decades-old mugshot of Davalos is displayed alongside photos of men DHS calls “Pedophiles, Murderers, and Fentanyl Traffickers.” The picture, he says, was taken not long after his arrests for robbery and burglary in the late 1980s.

In phone interviews, Davalos and his wife were open about his convictions. She said Davalos robbed a delivery person at gunpoint when he was 18, netting him $10 and a pizza. Davalos pleaded guilty to that crime, along with a later burglary she said involved him taking an $8 T-shirt. (Detailed files for the cases were inaccessible, but a criminal history report contained in the court record matches the time periods she described.)

Davalos was upset that the government portrayed him as a hardened criminal decades after he spent 13 years in prison.

“They’re trying to make me look dangerous,” he said.

After prison, Davalos worked as an electrician. His last brush with the justice system was in 2007 when he was convicted of misdemeanor spousal battery. Davalos’ wife said he threw a cup of water on her during an argument, something she has long forgiven.

Five years ago, injuries to his back made physical labor impossible, he said, forcing him to retire and rely on a cane to walk.

Davalos’ crimes would be long behind him at this point if not for a fateful decision before he was born: His parents both lived in the U.S., he said, but his father sent his mother briefly back to Mexico for his birth.

“He wanted me to be 100% real Mexican,” Davalos said.

His mother returned to the Los Angeles area with her new baby, eventually earning her own citizenship. Davalos has lived in the Los Angeles area ever since.

“All I know is LA,” he said. So he stayed, knowing he was constantly at risk for deportation.

As he and his wife tell it, Davalos was detained on June 16 while his wife drove him to a doctor’s appointment. On Pacific Coast Highway near the Marathon Los Angeles Refinery in Wilmington, Davalos recalls being stopped by two LAPD motorcycle officers who parked ahead of him and waved his car down.

In a rearview mirror, Davalos could see numerous Customs and Border Protection vehicles emerge. Within minutes, he was shackled in the back of a CBP van, he said.

An LAPD officer told his wife he was issuing her a ticket for driving 2 mph above the speed limit, Davalos said, a justification he doubted, considering LAPD officers appeared to know immediately who he was and immigration agents arrived moments later.

The LAPD confirmed that an officer “was there at that date, time and location issuing citations,” but said they were unable to verify the reason for the stop or the exact infraction written on the ticket, a picture of which Davalos provided to the Post. When asked why CBP agents arrived quickly on the scene to take Davalos, LAPD said they “do not have information on other agency arrests.”

It remains unclear how often local authorities collaborate with federal agents on such detentions. Long Beach and Los Angeles bar police from collaborating with federal immigration officials in most circumstances, including the agencies generally refusing to honor requests from Immigration and Customs Enforcement to hold prisoners for extra time so agents can retrieve them for deportation.

However, if a person has a significant enough criminal history, local authorities can circumvent a city or state sanctuary policy and assist in federal deportation proceedings, said Sanger Brito-Lyon, an immigration attorney based in Long Beach.

After his arrest, Davalos’ family could not find out where he was taken, with ICE’s online detainee locator turning up no results.

Finally, on a rumor, his wife drove to the federal building in downtown LA and demanded to speak to a supervisor. She was assured Davalos was being taken care of properly.

“They lied to me. They told me that he was in the infirmary,” she said, adding that she was told he was supplied a bed and was being fed Jersey Mikes’ sandwiches and Chipotle.

ICE did not respond to questions about Davalos sent on Monday. In a lawsuit filed this month, the American Civil Liberties Union and immigrant rights organizations have described “dungeon-like conditions” at the federal facility.

There, they say, roughly 300 detainees have been housed in the basement, “expected to sleep in cold rooms on floors without cots, bedding or blankets. Some are even forced to sleep in tents outside.”

At the press conference announcing the lawsuit, Fabian — an LA resident who declined to give his last name over fear of retaliation — said his wife was taken into custody on June 23, while on her way to work in Orange County. The last he heard, she had developed a stomach infection that forced her transfer to another facility for treatment.

DHS has contended that “all detainees are provided with proper meals, medical treatment, and have opportunities to communicate with their family members and lawyers,” but that failed to convince the judge overseeing the ACLU case, who issued a temporary order instructing the federal government to permit legal visitation “seven days per week” and provide free access to confidential telephone calls with legal representatives.

The judge on Friday also ordered a stop to what the ACLU alleges are indiscriminate immigration stops, during which people without criminal histories and, in some cases, even citizens, are stopped without reasonable suspicion that they are in the U.S. illegally. In the lawsuit, attorneys rely on firsthand accounts to argue that agents have detained people solely because of their “brown skin,” speaking Spanish or English with an accent or standing outside a Home Depot looking for work.

As of last week, ICE, along with CPB, say they have arrested more than 2,792 people in the Los Angeles area since June, according to a statement. Of those, at least 10 have come from Long Beach, according to a tally kept by the local immigrant rights group ÓRALE.

Data from the federal government shows that the majority of people arrested by ICE have no criminal history.

In a statement on Sunday, White House Spokesperson Abigail Jackson called the judge’s order Friday a “gross overstep of judicial authority to be corrected on appeal.”

“No federal judge has the authority to dictate immigration policy — that authority rests with Congress and the President,” Jackson said. “Enforcement operations require careful planning and execution; skills far beyond the purview or jurisdiction of any judge.”

Planning for a future in Mexico

Davalos and his wife both know his chances of returning to the U.S. are slim. She continues to petition for his return, though experts say there’s little that can be done for those who follow every rule to a tee, let alone a convicted felon.

Criminal cases like Davalos’ are known among immigration attorneys as “an immediate disqualifier,” regardless of the circumstance or whether the record was expunged, according to Brito-Lyon.

“Immigration law is not even,” Brito-Lyon said. “It wasn’t created, I don’t think, in a very thoughtful way. We don’t have a system that offers a second opportunity.”

Even those who follow every rule and never miss a hearing in their immigration cases can suddenly face deportation, something Brito-Lyon said he’s seen with his own clients recently.

Davalos’ best option, Brito-Lyon said, is to seek a hardship waiver that demonstrates a qualifying relative would suffer extreme hardship if the applicant were denied a visa or green card.

“They’re pretty tough to win,” Brito-Lyon said.

Staying at a rented apartment in Tijuana, Davalos’ wife visits him weekly, bringing with her his needed supply of insulin. Their four children, all of whom live in Long Beach, drive down regularly to keep him company.

“They love their dad, and he’s not going to be alone,” his wife said.

Every time his wife, a U.S. citizen, gets in her car in Los Angeles, she’s struck by a recurring fear that an officer will stop her and ask to see her documents. She said she knows it’s not likely, but she carries her passport at all times anyways.

“I’m scared they’re going to pull me over and take me,” she said.