You surely know, even if it’s just from watching classic movies or reading old novels, that there was a time when telephones were only used for making phone calls. You couldn’t so much as play Pong on an old phone, nor could you holler at “Siri” to ask it to tell you the capital of Vermont.

The early telephones were made of wood and pig iron and were the size of hi-fi consoles (which were, themselves, early and cumbersome versions of iPods, which barely even exist anymore because they’re old-fashioned and outdated).

But upon their introduction into household use, telephones were an amazing invention and, despite their limited and singular function, a highly desired novelty, allowing users to talk to friends and relatives miles away while sitting in their parlors.

Telephones began popping up in Long Beach in the early 1900s, with the advent of wall phones which had a hook on which users “hung up” the receiver at the end of a call.

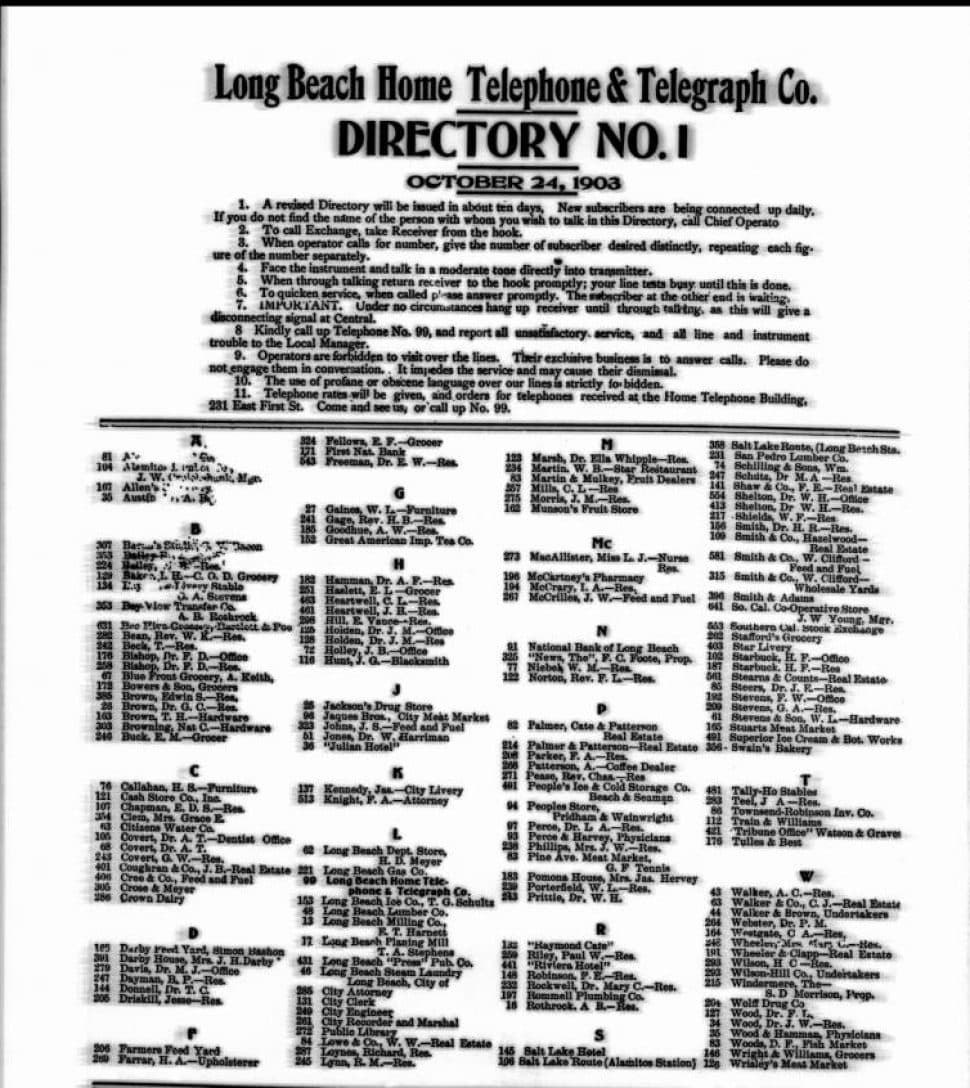

In 1903, Long Beach was a city of 3,000, and 169 of those people had a phone, which necessitated publishing a phone book for the town, so people knew which two- or three-digit phone numbers to call.

The city’s first phone book, very much unlike the Oxford English Dictionary-size directories of the 1950s through the 1980s, was a single sheet, listing the users alphabetically. And offering detailed instructions on how to use the telephone:

- To call Exchange, take receiver from the hook.

- When operator calls for the number, give the number of subscriber desired distinctly, repeating each figure of the number separately.

- Face the instrument and talk in a moderate tone directly into the transmitter.

- When through talking, return the receiver to the hook promptly.

There was more: No chit-chat with the operators. “Their exclusive business is to answer calls.” Idle chatter “impedes the service and may cause their dismissal.”

Finally—and this is important—“the use of profane or obscene language over our lines is strictly forbidden.”

The first local phone company was called Long Beach Home Telephone & Telegraph Co., founded by W.L. Porterfield. Its office was at 9 Pine Ave., and Bird Schilling was its first operator.

Let me put you on hold for a few decades….

In 1953, General Telephone Company was boss of the Long Beach phones, and the company threw a 50th anniversary party to mark the half-century since the issuance of the first directory.

The party, held at the swank Brower’s Restaurant on Pacific Avenue (it closed after 31 years in 1973), was attended by a group of original Home Telephone subscribers.

They included J.G. Hunt, who had been a blacksmith in town; Richard Loynes (namesake of the thrill drive in East Long Beach), who was 3 years old in 1903, but was representing his father; Carrie Walker, widow of Farmers & Merchants Bank founder C.J. Walker; Dr. Harriman Jones, the city’s first health officer and co-founder of Seaside Hospital; pharmacist Ed Jackson, in whose drugstore the first phone booth was installed (it went largely unused and ended up as a backyard decoration); attorney Fred Knight, who recalled paying $3 a month for his office in the Heartwell Building; and W.L. Porterfield Jr., the founder’s son, who reminisced with operator Bird Schilling about the early days when he was a youngster, “I used to sit on your lap and you showed me how to be a telephone operator.”

Another old-timer at the party was Charles Tucker, who lamented his absence from the celebrated listing. “I live way out in the country, then, at Fourth Street and Orange Avenue,” so he didn’t qualify for Home’s phone service.

In that half-century connecting 1903 to 1953, Long Beach’s population had exploded 100 fold to nearly 300,000 people, and the telephone more than kept up with the human numbers. The city’s phone directory in 1953 was 1,448 pages long. And, still, all telephones were good for was making telephone calls.