A new city report details the history of discriminatory housing practices that shaped Long Beach’s many neighborhoods in the post-war period.

First conceived in 2015 as an update to previous city-produced historical statements, the report will help the Cultural Heritage Commission in assessing potential historic properties for preservation, according to Developmental Services spokesman Richard de la Torre.

The 182-page report, titled “Historic Context Statement: Suburbanization & Race,” focuses on housing policies, and attempts to reform those policies, between the years between 1945 and 1979. It includes a list of 85 properties found to be historically important in the development of the city.

The report paints a complex picture of Long Beach, noting that while housing discrimination “was a fact of life for all people of color,” it also details how the city was a central player in later efforts to bring about fair housing in Southern California.

The report was produced by Pasadena-based Historic Resources Group for the city’s Developmental Services department. It was funded by a $40,000 grant from the state Office of Historic Preservation that was matched by the city, according to de la Torre.

Sharon Diggs-Jackson, who was a member of the city’s 2020 Redistricting Commission and was one of the first Black students to attend Wilson High, was interviewed by the report authors about her experiences growing up. She said found the completed report “fascinating,” even though she lived through much of what it discusses.

“Putting it together was a huge task,” she said. “It’s welcome information and I’m so glad it’s documented.”

The city’s Cultural Heritage Commission briefly discussed a draft of the report at its July 26 meeting.

For Commissioner Tasha Hunter, the report was “very important” because it explained the policies and practices that led to different ethnic groups living in different parts of the city, resulting in de facto segregation.

“Eastside to Black folks meant Cherry because they weren’t allowed to go past Cherry at night,” she said.

Fellow commissioner Mary Hinds also said the report was very important, but added that some of the information in it regarding Poly High, which the report describes as a “microcosm of the story of the diversity in the city,” was not consistent with her experiences there as a student in the early 1960s. Hinds said she would follow up with staff but did not elaborate on what concerned her.

Though considered very progressive today, Long Beach a century ago was anything but. In 1926, 30,000 Ku Klux Klan members paraded down Ocean Boulevard while aircraft with illuminated KKK insignias flew overhead. It’s estimated that 5,000 of the marchers were Long Beach residents, according to the contemporary news accounts of the parade.

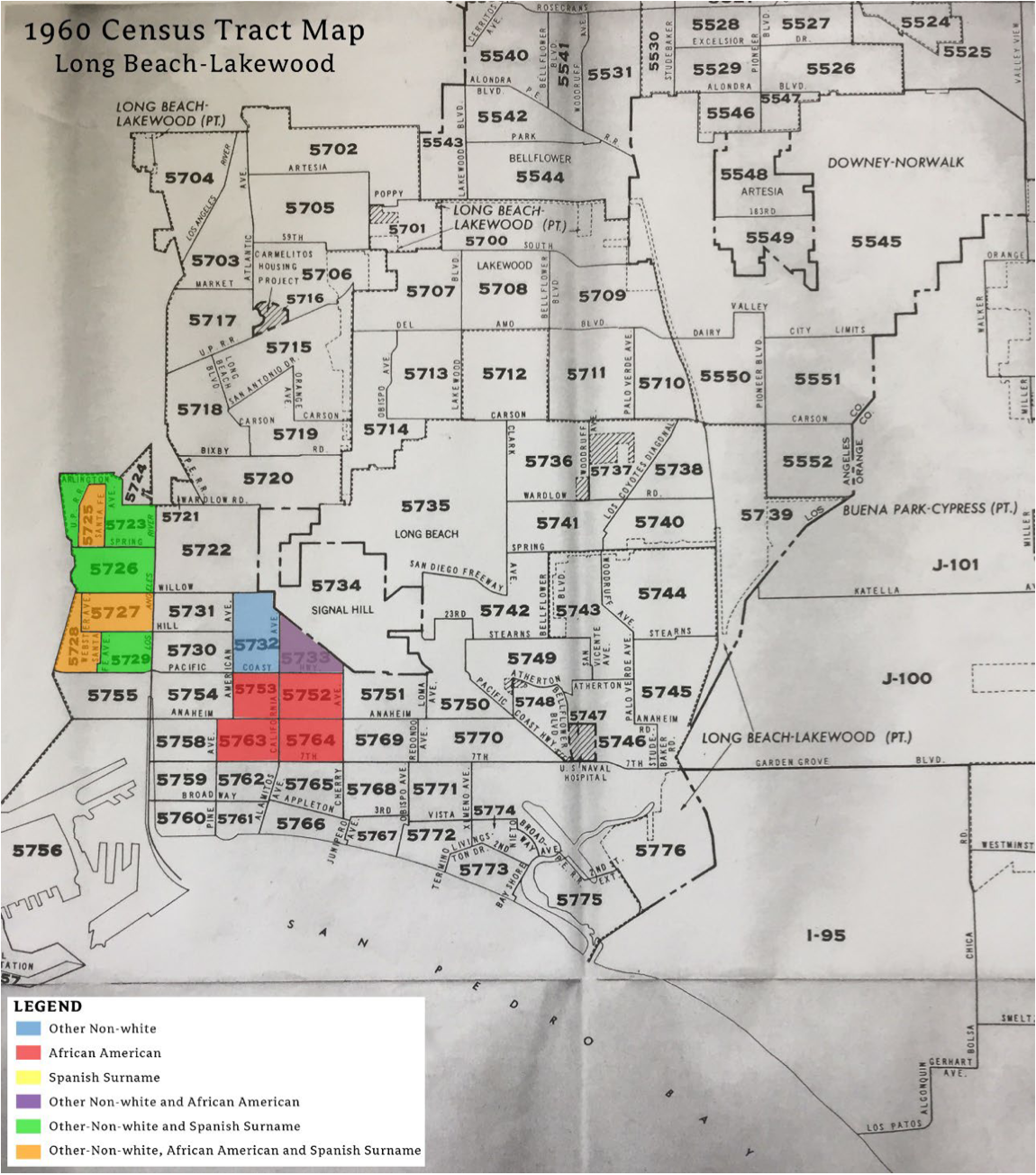

World War II brought many Black people to Long Beach to work in defense plants, but racist restrictions written into deeds and the practice of redlining—where banks deemed neighborhoods with non-White residents to be “deteriorating”—made buying homes in largely White neighborhoods all but impossible, according to the report.

“Virtually all of the new housing developments were subject to restrictive covenants and off limits to people of color,” states the report. “Prior to the 1960s, Long Beach landlords and sellers could legally refuse to sell or rent to these populations.”

By the 1950s, when Black and other minority residents were finally able to begin moving into White neighborhoods, they faced a host of challenges including “vandalism, cross-burnings on lawns, racial slurs, and anti-integration petition campaigns,” according to the report.

They also had to contend with the practice of “blockbusting,” in which White residents sold their homes out of panic that an integrated neighborhood had lower property values. Realtors then resold the homes to minority residents at inflated prices, according to the report.

Blockbusting radically changed West Long Beach, with White residents going from making up about 82% of the neighborhood in 1960 to about 55% just eight years later, according to the report.

What’s more, Black residents who did manage to buy homes could not get insurance from the Federal Housing Administration, according to the report. As a result, Black buyers had to buy homes on “installment plans” in which they accumulated none of the equity afforded to White homeowners, according to the report.

In these sales, missing a single monthly payment could lead to the eviction of the Black homeowner. As a result, these sales “often resulted in couples working double shifts to make payments and to defer maintenance,” according to the report.

Even Black professors hired to work at Long Beach State College (later called Cal State Long Beach) had to find housing miles away from the school because deed restrictions prevented them from buying homes in the new East Long Beach neighborhoods close to the school, states the report.

In an attempt to end these practices, local attorneys and members of the clergy dedicated to civil rights formed the Long Beach Fair Housing Foundation in the early 1960s.

By 1964, the foundation helped place seven Black families in permanent homes. Within a decade, that number jumped to 1,500, making the organization a “model for other fair housing organizations throughout California and the country,” according to a city presentation on the report.

The city is asking for public comments on the report, which can be emailed to [email protected]. The deadline to comment is 5 p.m. on Friday, Aug. 5.

The commission is scheduled to discuss the report again at its Aug. 30 meeting.