Outside a convenience shop on Seventh Street, Isaac Martinez waits with a hunter’s disposition as his prey heads straight into his gun sight.

A Hyundai Sonata has surged from a pack of cars and is closing fast from a distance of several hundred feet. Martinez pulls the trigger on his lidar gun, which emits a muffled beep before a flash on his digital display reads 50 mph — in a 30 mph zone.

Martinez has been driving a Metro bus around Long Beach for about a year and said he’s noticed the afternoon drivers are typically more aggressive. Driving a bus in the city, Martinez says, it’s a practice in “testing your patience.”

Regional data says he’s right. The most dangerous time of day to walk or ride on Long Beach streets over the past decade: 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. on a Friday. Pedestrians were most likely to be struck by speeding motorists or those barreling through crosswalks.

Cars Martinez clocked careening by this stretch of Seventh Street are among the 6,700 scofflaw drivers the city says speed at least 11 mph over the limit on this 1.3-mile stretch between Cherry and Termino every day.

It’s a frustrating reminder, Martinez says, of an obvious problem the city knows about but has deliberately taken a slower approach to resolve.

Long Beach is one of seven cities that fought for the right to test speed cameras on its deadliest streets. But since Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2023 signed the pilot into law, Long Beach has only taken limited steps to advance the program — even as other cities have either begun issuing tickets or made penultimate arrangements.

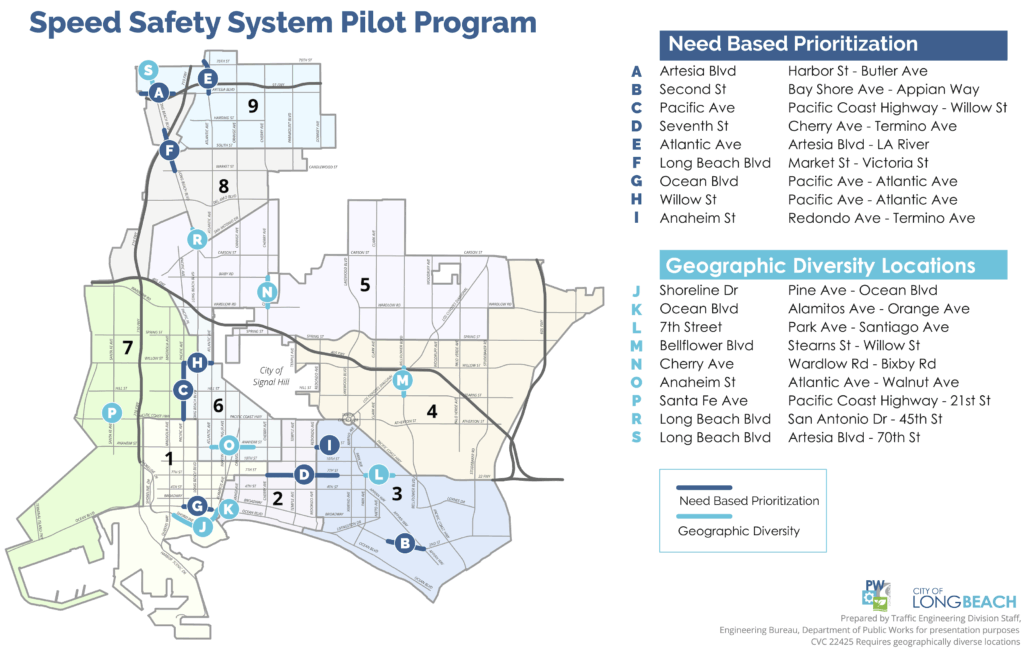

Local traffic officials last week unveiled the proposed locations for the 18 cameras and explained the reasoning behind their placement, saying they were chosen for their high rates of street racing, speeding and pedestrian collisions. Seven of the nine locations are also in a school zone.

Following a City Council adoption in December and subsequent preparations in the spring, Long Beach hopes to have cameras installed in the summer for a 60-day period during which owners of speeding vehicles will only receive warnings. Tickets could start going out by November 2026.

Long Beach officials say their rollout has been intentionally slow, as they wait to see how the tactics used in other cities play out before they mimic them. But the timetable provided has received mounting criticism, with residents and advocates pleading that any plan to slow drivers must be sped up.

“It’s embarrassing because they opted in to be part of the pilot,” said Damian Kevitt, the CEO of road-safety group Streets Are For Everyone. “They lobbied the governor, they lobbied legislators to say, ‘We want to be part of this.’…Where’s the disconnect?”

Under the five-year pilot, cameras will issue owners of any car speeding over 11 mph a fine of $50, with a cost escalator up to $500 for those driving 100 mph. Tickets can be paid, negotiated down as much as 80% based on income level or swapped for community service. Data is erased once the ticket is resolved.

Revenue from the fines will go back into the program, with leftover money used to pay for traffic calming improvements, like speed bumps, flashing beacons and lane narrowing.

And so far, it’s been a boon in cities where it’s been carried out.

Kevitt and others look to the success seen in San Francisco, which last week entered its third month of issuing citations. From June to August, the city issued more than 260,000 warnings to drivers. A smaller study found that speeding dropped 72% at 15 camera locations, which equates to about 20,000 fewer speeding drivers each day.

Shannon Hake, a planner with the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, said the policy has been transformative. Many of the roads with cameras, once among the most nefarious in the city, “feel like a street again.”

“Not like it’s a freeway, and you’re taking your life in your hands, you know, trying to cross the street,” Hake said.

The city, Hake explained, had been pushing the state legislature to bring this bill forward for 14 years. The day after it was signed, San Francisco transportation workers were immediately reassigned to the pilot.

“We didn’t want to wait one more moment,” she said. “So even though that meant taking myself and other folks off of other projects to do this, we absolutely started moving at light speed.”

In the months before, San Francisco “painted the town with information,” Hake said, as a means to help people adjust to the program fairly as opposed to installing cameras and ticketing without much notice.

“We had billboards up, we had ads on YouTube,” she added. “We had our buses covered in bus wraps. We had announcements in our stations. … We went door to door to talk to businesses and let them know, ‘Hey, these cameras are coming.’”

Three of the seven pilot cities — Oakland, Glendale and Malibu expect to have their cameras online and at least issuing warnings by the end of the year. San Jose planned to have it online this year but was stalled until next year by a temporary block in federal funding by the Trump administration.

With the release of Long Beach’s report on potential camera locations last week, Kevitt says the city may slightly outpace only Los Angeles, which faced a billion-dollar budget shortfall, potentially stymying its 125-camera plan. An LA City spokesperson said Thursday they nevertheless hope to have 125 cameras online by summer 2026.

Aiming for efficiency instead of swiftness, Long Beach has copied from frontrunners like Oakland and San Francisco — piggybacking off vendor contracts, policy language and staffing plans, Joshua Hickman, acting director of the Public Works Department, told a City Council committee last week. As the law is written, Hickman pointed out, the city has until 2028 to start the pilot.

It’s a change in tone from 2023, when Long Beach, along with the other pilot cities, advocated heavily on the bill’s behalf and acted as a co-sponsor. Mayor Rex Richardson, in a May 2023 opinion article, said the city must take “immediate steps to reduce speeding and save lives,” instead of letting speed camera technology collect “dust on our shelves.”

The city did not make someone available for an interview about the process, instead referring to the Oct. 7 committee meeting and its most recent report.

In a statement after this story was published, the mayor said, “Our goal has always been to design a program rooted in data and community need — one that advances public safety while upholding our commitments to equity, transparency, and privacy. Long Beach has benefited from lessons learned in San Francisco, which pioneered the legislative framework, and from collaboration with partner cities launching around the same time.”

Since the bill was signed in October 2023, according to state collision data, there have been more than 3,200 crashes in Long Beach — of those, more than 20% resulted from speeding.

In this year alone, city police have reported 44 traffic deaths — already outpacing those 40 killed last year, according to local road safety group Car-Lite Long Beach.

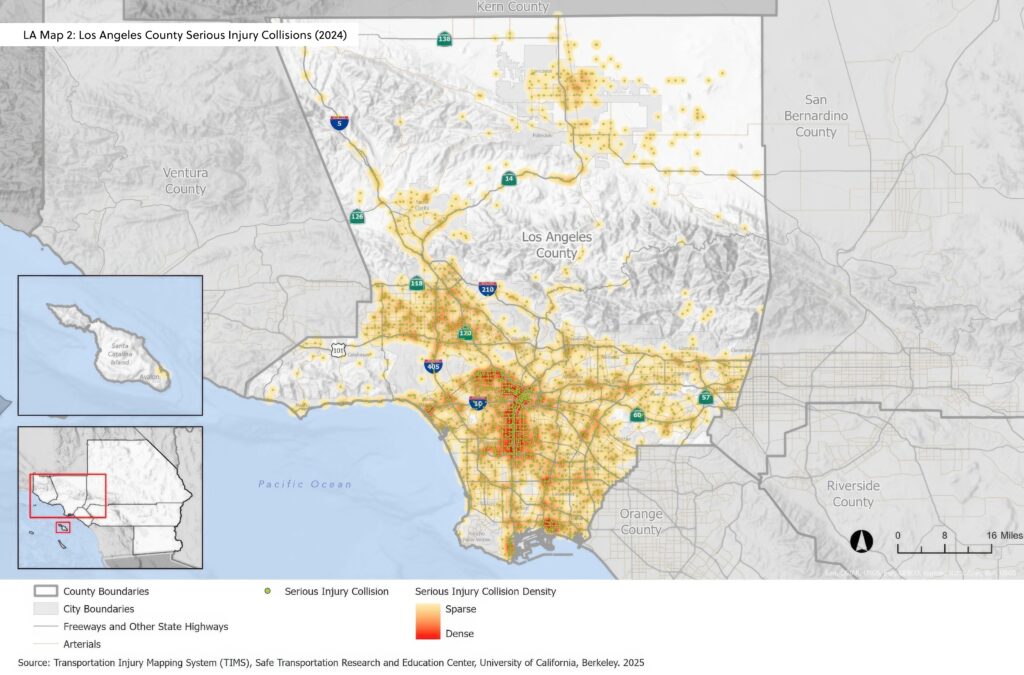

Long Beach, over the past decade, has proven to be among the deadliest cities for pedestrians in Southern California. According to a 2025 report released last week by the Southern California Association of Governments. The city from 2014 to 2024 saw more than 400 people killed and another 40,000 injured by collisions.

“It’s not acceptable to just watch people die knowing that you’ve got technology to save lives,” Kevitt, of Streets Are For Everyone, said.

Staff writer Jacob Sisneros contributed additional reporting to this story.

Editor’s note: This story was updated with a statement from Mayor Rex Richardson.