Long Beach resident Evangelina Ramirez was one of many residents who asked for an extension of the public comment period on the 710 Freeway project’s environmental documents. Photo: Jason Ruiz

Long Beach has changed a lot over the last 60 years. It’s population has nearly doubled, the downtown skyline has changed dramatically and its port has grown into one of the busiest in the world.

To accommodate that growth, both the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach along with CalTrans and Metro have proposed a makeover and modernization of the main artery carrying goods out of the port complex and to their final destinations.

The group insists that the increased traffic volumes and population growth forecasted in the next few decades cannot be sustained by the 710 Freeway as currently built. So, a proposal nearly 20 years in the making, which would give the 60-year-old 710 Freeway a considerable facelift, is nearing the end of a mandated public review of its environmental documents. But residents living near the freeway want more time.

A final public hearing for the recirculated environmental impact report which included the three final options for the 710-Corridor project was held last week at the Cesar Chavez Park Community Center in Long Beach where a capacity crowd turned out to request just that: more time to review the documents for the project that will undoubtedly have a lasting impact along the 710 stretching from Ocean Boulevard in the south to the end of the project scope at the 60 Freeway in East Los Angeles .

The August 31 meeting was the second night in a row that residents in the area turned out in droves to have their voices heard, specifically on the environmental impacts the project could have on a portion of the city that’s already inundated with pollution from port traffic, refinery emissions and the 710’s proximity to homes and schools.

A table in the middle of the community center held notebooks of environmental documents for the public to review.

An effort to explore ways of decongesting traffic in the region began in the early 2000s and included about a dozen project alternatives. However, through years of public meetings and refining those options the recirculated documents have been boiled down to just three choices.

The three alternatives would have very different impacts on the roughly 20 communities surrounding the project. CalTrans contends the first alternative, to build nothing, would simply allow projected growths in traffic volumes from both the ports and a growing population to further clog the freeway with traffic stemming from overcrowding and an accident rate that outpaces other stretches of freeways in the region, something it attributes to the intermixing of cars and heavy duty trucks lugging cargo to and from the ports.

Alternative 5C would widen and modernize the freeway. That would expand the 710 south of the 405 Freeway from six lanes to eight lanes and from eight lanes to 10 lanes north of the 405. It would also include various interchange improvements and ramp meters to help facilitate the truck traffic on the 18-mile stretch of the freeway. That project alternative is anticipated to cost about $6.5 billion.

Alternative 7, the most expensive of the three options, would include a “clean emission corridor” from Long Beach to the City of Commerce that would incentivize truck drivers and the companies they work for to switch over to zero or “near zero” emissions trucks in order to access the lanes.

That alternative is projected to cost $11 billion and is supported by community groups in Long Beach and other surrounding cities who are also pressing the ports to speed up their clean air action plan goals that currently aim for a zero emissions port complex by 2035.

“My community is already suffering from the daily impacts of pollution and I personally know friends, neighbors and family members that have asthma, cancer and other types of diseases,” said Kimberly Amaya, a member of the East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, a group that is pushing for alternative 7. “I just want to see zero emissions in the project because the community, as I said before, is always impacted by the pollution and we deserve to have clean air.”

Rene Castro, director of Community Engagement at Century Villages At Cabrillo, an affordable housing project located just west of the 710, referred to the Village’s location as the “diesel death zone.” Midway through speaking in favor of alternative 7, he took out the air filter mask he wears when he rides his bike to work to limit the impact of the pollution he breathes in.

“If I don’t use this air filter my lungs are on fire,” the 53-year-old Castro said. “I’m a very healthy individual. I don’t live there, but I spend about eight to ten hours there a day. I do not know how we can put a price on our children’s health. I’m all for alternative seven. I don’t even know why this is a discussion.”

A report put out by CalTrans states that truck traffic along the segment of the 710 in Long Beach accounts for about a third of all traffic while only totaling between 6-13 percent elsewhere in the county.

Ron Kosinski, deputy district director of environmental planning for CalTrans, recounted his own childhood growing up in North Long Beach and acknowledged that his family too suffers from asthma, but alluded to the reality that perhaps no alternative could come with a happy ending.

“We recognize that all the project alternatives will have a significant adverse affect on the community,” Kosinski said. “If we do nothing, leave things as they are, you’re basically seeing these trucks and the various health issues that are related to the trucks going to the ports and using the 710, it’s a situation that is really challenging. Certainly for people living here.”

There are numerous concerns aside from the emissions and particulate matter that are currently being generated by the 710 diesel truck traffic and the daily congestion that clogs the freeway.

Displacement of those around the freeway that could see their homes or businesses bought up by the state if the approved alternative requires their land to expand the 710 was one of them. The project dictates that any person required to move as part of the project would receive help with costs associated with buying or renting a new home, but only within 50 miles of their previous location and only for “actual reasonable” costs.

The other main concern was the time in which the public had been given to review the project material. The inside of the community center was lined with representatives ready to explain the impacts of traffic, emissions and detail the schematics and mock ups of the multiple iterations of the projects, some of which will include a tangle of freeway interchanges to better separate truck traffic and auto traffic.

The portion of the cities that surround the 710 corridor are largely working class, immigrant families, many of whose native language is not English. Even if the draft EIR weren’t written in the customary technical industry jargon that is expected in those types of documents, the sheer breadth—hundreds of pages long—would take any person a considerable amount of time to read.

“It’s hard for us to understand the language that you use in your reports in your things,” said Evangelina Ramirez. “One of the things that we want to ask you is giving the community more time to understand what is going on in those documents.”

California State University Long Beach political science professor Amy Cabrera Rasmussen said that the project should fully endorse and incentivize zero emissions, avoid displacement where possible and prioritize training and local hire programs to benefit the communities that would be affected most by this project. She echoed the attendees’ requests for an extension of the public comment period by 120 days.

“This 710 project is a rare moment where real and significant improvements to community health are possible,” Rasmussen said. “But only if our actions and plans are bold, that they have teeth, and they clearly incorporate community needs and priorities.”

“I have a PhD and I still haven’t made it through the entire draft,” she said.

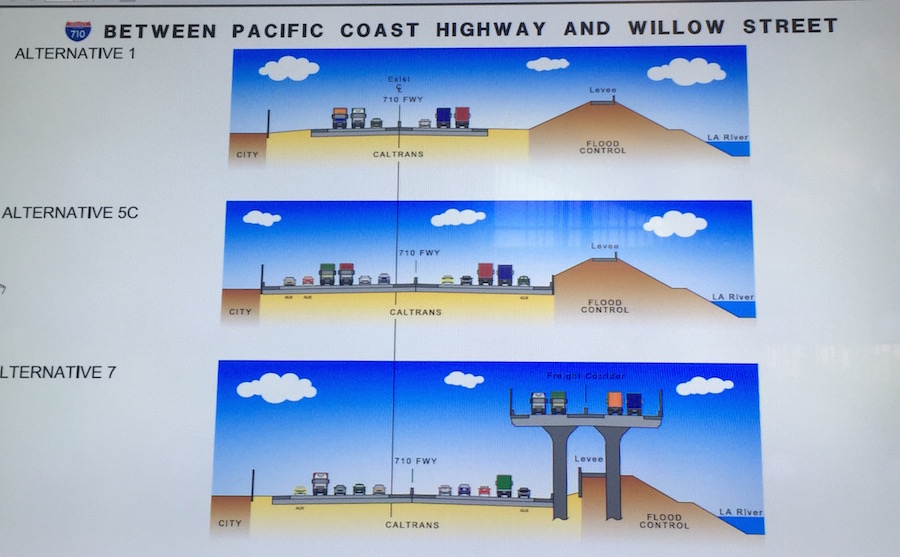

A cross section of proposed changes to segment of the 710 Freeway between Pacific Coast Highway and Willow Street.

While the existing freeway would change very little in regard to height, additional truck-only bypasses would extend well above the current lanes with the pillars holding up the over passes potentially displacing residents and in some cases, narrowing the levees alongside the Los Angeles River.

The tallest of which would be the ones propping up a proposed interchange addition where the 710 meets the 91 Freeway (180 feet).

Kosinski said that all public comments during last week’s meeting would be taken into consideration, including the numerous requests to extend the public comment period beyond the current October 23 deadline. However, he added that he doesn’t expect every member of the community to read the entire EIR, stating that “people will naturally be drawn to the sections that interest them the most.”

A final decision on a possible extension of the public comment portion for the recirculated EIR could come by the end of the month. If it moves forward to the next stage of the planning process multiple members of the design team agreed that the project is still years, if not a decade from breaking ground.