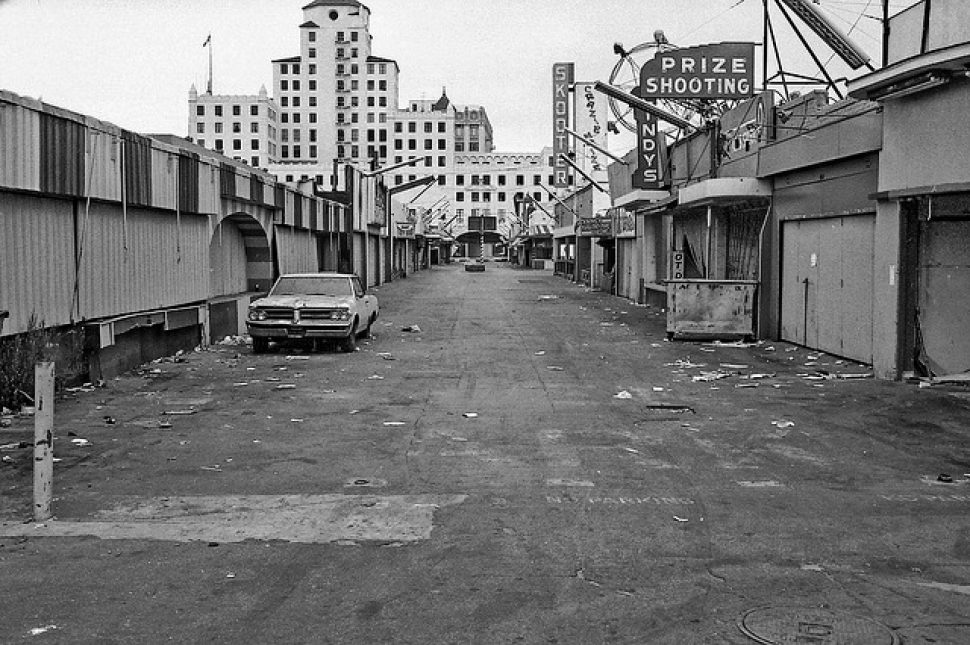

Our ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings, places and things that have either been demolished, are set to be demolished, or are in motion to possibly be demolished—or were never even in existence. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural and spatial history. To keep up with previous postings, click here.

****

In 1963, 18-year-old self-appointed savior Jeri Nunn had annulled her marriage, lost an unborn child, and had a contract on her head: $500 for the person who would assassinate her.

Nunn meandered the streets of The Jungle, roughly south of Ocean Boulevard and west of Magnolia Avenue in Downtown. During the night, during the day, Nunn was searching for clues that would fulfill her voluntary mission of conning cons into her giving her information that would halt the spread of narcotics that she felt she “had to do something about.”

So she volunteered as an informant for the LBPD, ultimately leading to the arrest of 14 men and four women—and once her disguise was uncovered during the trial of one of those arrested, her life was perpetually threatened.

Her story was part of Long Beach’s head crime reporter Bill Hunter’s five-part series of articles on The Jungle for the Press-Telegram. He described it as a place of “immorality and sexual deviation” that was “beyond the control” of the Long Beach Police Department.

Despite the judgmental overtones—quotes from officers and officials throughout Hunter’s series consistently demonized the poor folks who lived there, despite the fact that it was the only place they could afford—it is actually easy to understand how such a small place could get out of control. In its tiny plot of land, what is now known as the minuscule patch of grass dubbed Santa Cruz Park, there were three cocktail bars, two liquor stores, and a beer tavern. It was home to “more ex-convicts and dishonorably discharged servicemen than any other area in the city.”

In one of Hunter’s pieces, the caption to the cover story’s photo read: “‘Born to Lose’ is the way to describe many Long Beach ‘Jungle’ area inhabitants like the pair shown in this unposed photo. Young man’s tattoos include the word LOVE on the knuckles of his left hand. (On his right hand is the word HATE.) He wears an ornate ring on his left ear. His girlfriend’s hair is bleached and stringy. Her face is marred by long scratches from a recent fight.”

Hunter’s series of articles prompted an editorial from the paper, noting that it was a place where “poverty, dope addiction, sexual misbehaviors, violence, and petty crime” flourish.

It was the home of the camp of ladies known as the Hamburger Queens—named so because their sexual favors were offered for the price of a burger—where they stood in the only heels they could afford, roaming The Jungle’s interiors and backdoors before takin’ a Naval officer to a place where they could more appropriately conduct business. (Or spread infections: the STI rate was 115 times higher than any other area of the city, a testament to both the hard work of the Queens and their ability to somehow stay alive.)

The Independent, Press-Telegram didn’t mince words in its editorial, not stopping from outright damning the neighborhood:

It’s not the worst place in the world but it does require special police effort just to keep the place from exploding. It is a center of venereal disease. Its denizens push narcotics and dangerous drugs. It is a cancer, though not a large one, in an otherwise healthy city.

Readers [are asking], “What can be done about it?”

There is only one answer: surgery. The Jungle exists because it provides housing suitable to the pocketbooks of its desperate residents. If the housing is removed, they will go elsewhere.

Where will they go? Most of them will seek comparable housing. It is to be hoped that they can’t find it in Long Beach. The decent people—there are decent people in The Jungle—will find homes in better neighborhoods.

In 1963 alone, the Long Beach Police Department arrested at least two people every day in The Jungle, with some 200-plus crimes occurring in the first half of the year alone.

This wasn’t always the case with The Jungle (or the eventual downtrodden Pike). It was, initially, a resort space where folks came to enjoy the sand and sun. Post-World War II, with the influx of sailors due to the Navy presence in Downtown, things began to change, with sailors seeking thrills to get their rocks off.

By 1961, when Long Beach’s Redevelopment Agency was formed, its first order of business, as journalist Matt Cohn noted, was The Jungle.

Soon, articles began to sing praises of “the development on West Beach” that would be coming—and they were eventually right. Now, the area is home to precisely what Hunter and others were hoping for: Gleaming office towers, maintained properties and an almost complete lack of crime if not an equal amount of sterility and banality.

But one can’t help but give props and recognition to the down-and-outs, the dirty tricksters, the hookers and their patrons, the tatted hot messes that were so virulent and dedicated to the many pleasures of the underbelly that they created their very own wild, unpredictable jungle.

Brian Addison is a columnist and editor for the Long Beach Post. Reach him at [email protected] or on social media at Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.Long Beach Lost: The Jungle, Downtown’s play den for ‘immorality and sexual deviation’