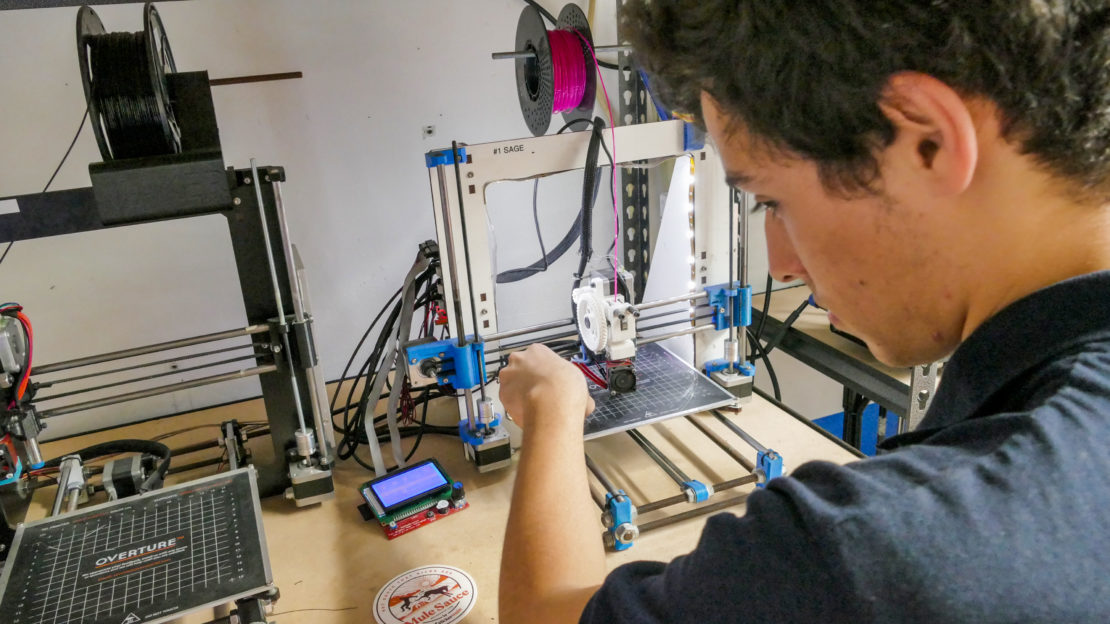

In the confines of a small storage warehouse on the outskirts of Long Beach and Garden Grove, a group of 20-somethings are fast at work. Some, wearing latex gloves and face masks, stand in a makeshift assembly line and dip brightly colored plastic strips into clear disinfectant liquids. Others stand hunched over small machines that emit a cacophonous whir; something akin to the tune of a dozen computer cooling fans kicked into high gear. After an hour, the drone becomes white noise. After 12 hours, they don’t notice it anymore.

This team of engineers belongs to a 3D printing lab known as The Maker Society. Originally a 3D printing club at Cal State Long Beach, the club is now a recently opened small business, owned and run by current and former CSULB students.

During more typical times, owners Daniel Curry, Carlos Vergara and Ambreen Khan would be processing and printing maybe a few dozen projects for students or superhero cosplayers seeking plastic alternatives to armor. But these days, they’re crafting face shields for medical personnel using 3D printing technology.

“We’ve been staying up sometimes all night doing the face shields, fixing printers and making sure that they’re properly assembled and sterilized,” said co-owner Khan, a civil engineering senior at CSULB.

The face shields completely cover the wearer’s face and are meant to be used with N95 or surgical masks as an extra protective layer to guard against bodily fluids spread from sneezing and coughing. Their goal is to get these shields into the hands of healthcare workers in hospitals all over Southern California who are in dire need of personal protective equipment during the coronavirus health crisis.

“I was just thinking, OK, maybe we’ll just help our local hospitals, the V.A, which is right next to Cal State Long Beach, maybe St. Mary’s downtown,” said Carlos Vergara, who graduated from CSULB last year with a degree in aerospace engineering. He says he found the initial face shield design while scrolling the web on his lunch break.

“But now we’re getting requests from all over the place, and we will be sending something to Minnesota soon, for the Mayo Clinic. So everyone’s requesting these now.”

When The Maker Society launched their GoFundMe campaign on March 28 to raise material costs for 200 face shields, they weren’t confident they would reach their goal but agreed they’d start producing the masks anyway. To their surprise, the goal was achieved a day later.

“We honestly did not expect the traction that we got,” Kahn said. “We got more than $1,000 within the first 24 hours.”

With the outpouring of support, they’ve since upped their goal and now aim to produce 1,000 face shields and donate them to local hospitals all over Southern California. Seventy-seven people have donated more than $3,000 so far, but at a $5 material cost per unit, they’re about $2,000 shy of their goal. Even though their overhead costs haven’t been met yet, their plan is to keep printing with the hope that the funds will follow.

“So far we’ve delivered over 250 [face shields to hospitals],” Curry said. “We have 250 more that will be delivered this week.”

There are two kinds of face shields that Curry and his partners are printing, the main differences being the size of the headband and the type of plastics used.

The first and original design was borrowed from Prusa Research, a 3D printing company in the Czech Republic.

“Their design was approved by the Czech Ministry of Health,” Curry said. “I think they’re still in the process of producing 20,000 of them all over the place.”

The Prusa design features a thin headband made with PLA, a low-cost and more common type of plastic. Those masks are intended for single-use and require little over an hour of printing to produce.

The second is a design approved by the U.S. National Institute of Health. Its shape is similar to the Prusa design but has a wider band that covers the entire forehead. The NIH masks are printed with PGG filament, a popular request among hospitals because of the plastic’s higher warping temperature. The durable material means hospital workers can reuse masks several times because they can be cleaned in a sterilizing oven; however, the NIH masks take about four hours to print.

In total, The Maker Society is printing 25 to 30 of the NIH approved designs while simultaneously printing about 100 of the non-approved designs each day.

“From what I understand, there’s a lot of confusion with how a lot of hospitals are choosing to do things,” Curry said. “So the hospitals themselves aren’t allowed to officially accept certain equipment; however, with the shortage of equipment right now, they are requesting that their employees basically bring whatever they’re able to use.”

Once the headbands are printed the team assembles, sanitizes, packages and seals the face shields. The team wears gloves and N95 masks while sanitizing with isopropyl alcohol, as instructed by the NIH. Once the gear is sanitized and air-dried, they package the shields and store them for three days to ensure any potential virus or other bacteria dies on the surface.

“We’re trying to keep it as clean as possible,” Vergara said. “We change the tablecloths every four hours and sanitize every day—sometimes three times a day.”

Three other engineering students from CSULB are now donating their time to help assemble and sanitize the shields. During the first few days, Curry admitted that he and his business partners were working 12-hour shifts to keep up with production needs. They’ve since adjusted to working in more manageable shifts where they clean and assemble every other day.

The Maker Society team has personally reached out to various hospitals in Long Beach and beyond. Kaiser Permanente has accepted a batch of their shields for testing. St. Mary’s appears to be on board. Good Samaritan Hospital in San Jose has requested their shields along with other private medical facilities in Southern California. U.S. filament manufacturer, Atomic Filament is also donating their materials to any 3D printing company producing the masks; Curry says they’re looking into working with them as well. But their greatest alliance, so far, is with Masks for Docs, a nationwide nonprofit that’s working to bring medical supplies and personal protective gear to dozens of hospitals all over the country.

With the face shields, Curry says they’re busier than ever. Although encouraged by the new business, the team looks forward to a return to normalcy, when print orders revolve once again around student projects and the occasional cosplay commission.

“Danny commissioned an Iron Man suit for a YouTuber, actually who wore the suit in his video,” Kahn said. “That was enough to support us for the first month.”

The YouTuber Kahn is referring to is King Vader. He wore the full-body Ironman suit, which took over a month to print, in his Endgame parody video. You can spot Curry dressed as Star-Lord from Guardians of the Galaxy at 3:10 in the video below.

“For now, we’re focusing more on just being able to help out the community when it comes to learning about technology as well as giving access to printing services for those who need them,” Curry said.

To donate to The Maker Society, check out their GoFundMe campaign, here.