Our ongoing series, Long Beach Lost, was launched to examine buildings, places, and things that have either been demolished, are set to be demolished, or are in motion to possibly be demolished—or were never even in existence. This is not a preservationist series but rather a historical series that will help keep a record of our architectural, cultural, and spatial history. To keep up with previous postings, click here.

****

After the Long Beach Land and Water Company became the owners of Willmore City—named after W.E. Willmore, the projector of the colony scheme our city was initially built upon—and officially named our city Long Beach, development sparked.

A hotel was built between Pacific Park and the beach on the bluff, prompting an old horse-driven cart that connected Long Beach with Wilmington to be replaced by a spur of the Southern Pacific Railroad. This caused the town to boom—as Alan Burks of Environ Architecture pointed out, “It was the beginning of Long Beach”—leading to the building of the once-iconic Jergins Trust Building.

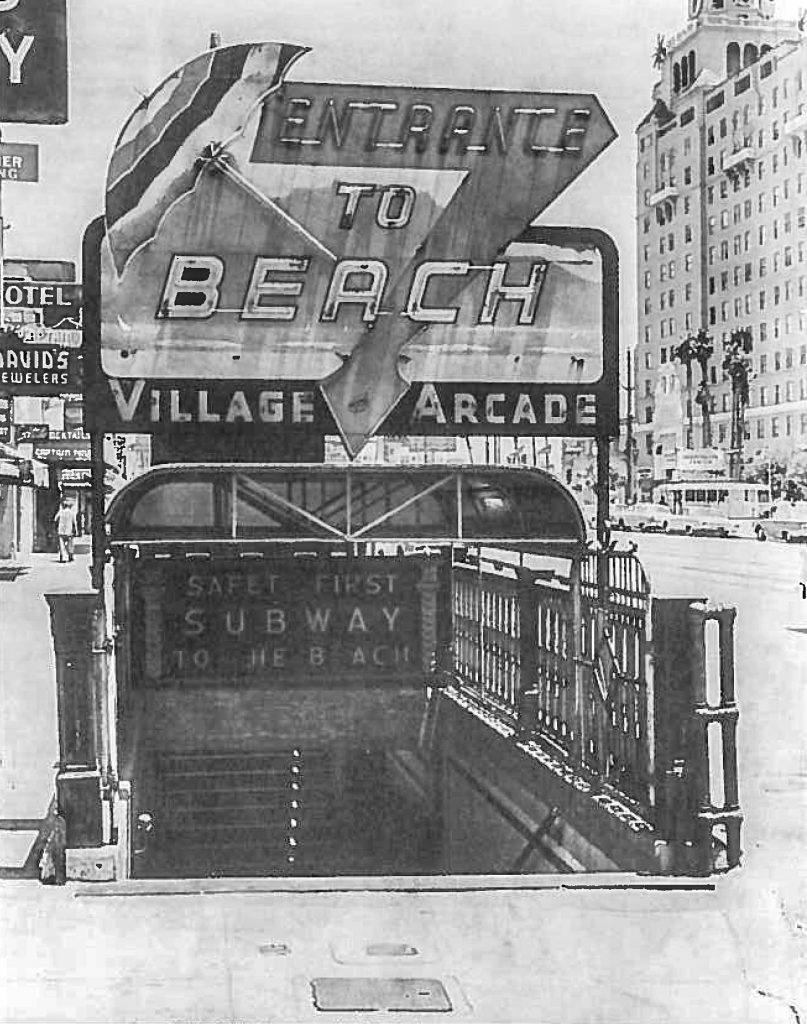

The building, sitting on the southeast corner of Pine Avenue and Ocean Boulevard, became an essential development attraction, particularly its Jergins Tunnel.

Then-councilman Alexander Beck created the tunnel in 1927—which still exists—that went under Ocean and connected to the building. Businesses existed in the tunnel selling goods while people passed on their way to the beach. It was built because, at its peak, Pine & Ocean was seeing some 4,000 people crossing the intersection per hour on the weekend—a number we could only hope for in a single day in 2018.

In 1988, however, the destruction of the building sparked what many feel was the beginning of the downturn of Downtown. Urban legend holds that the city itself cheered its destruction when, in fact, it fought it: The owner of the building’s original request for a demolition permit was denied but, after claiming he simply could not afford a refurbishment, the city then granted the permit.

The tunnel has since remained closed to the public, though that may soon change. The City of Long Beach opened the tunnel for potential real estate investors interested in not just purchasing and activating the tunnel but buying the entirety of the 100 E. Ocean property. (Part of the city’s Long Range Property Management Plan, this is one of many former Redevelopment Agency (RDA) parcels of land the city auctioned off.) It was purchased by an investor in 2016 who plans to turn the property into a massive hotel.

Ocean and Pine is a particularly important cog with regard to connectivity, given that it exists as the clearest crossroads of linkages between historic Pine Avenue, the Pike development, the Aquarium, the Promenade, the Convention Center, and the waterfront. And the reason for it acting as the future link between these areas is because it once was the link to a bourgeoning Downtown scene.

Jergins Trust was a key part of fostering what became the wildly popular Pike, a stretch along Seaside Way that even went through Jergins’ western sister, the Ocean Center Building.

After the Jergins building came down, things took a bad turn: the $130 million Pike redevelopment became an absolute fiasco, lacking to this day any significant form of foot traffic and being removed from the Downtown Plan due to planning zone requirements; Seaside Way, the once kinetic stretch of passersby, now serves mainly as a utility road for the sprawl of apartment complexes with little to no foot traffic on any level and residential developments that lack height or interest; the former site of the Jergins Trust building has sat, since 1985, empty; the liquidation of the RDA has troubled or flat-out eradicated improvement plans; and the tidelands surrounding the space deeply affect the way in which things can be built.

One can only hope that the property’s new owners understand the importance of the space.