On the first day of the spring semester, a student stepped into Cal State Long Beach’s virtual reality system and began piloting a flight simulation.

Kieran Whitney, a third-year undergraduate in computer science, donned special glasses to see the 3D panorama before him and used a joystick to operate a virtual flight, taking off from San Francisco’s Embarcadero.

The simulation is part of a collaboration between the university’s psychology and mechanical and aerospace engineering departments to study how humans operate “urban air mobility vehicles,” akin to air taxis. About a decade ago, NASA pioneered the concept as a way to revolutionize metropolitan travel by creating on-demand air transportation, said Panadda (Nim) Marayong, one of the professors leading the project.

UAMs are the “newer version of helicopters,” said Kim Vu, another professor on the project. But while helicopters are noisy, these new electric-powered vehicles will be quiet and low-emission, designed to travel to high-traffic locations (like airports) via well-developed routes (like highways).

When it starts, the service will likely be expensive, but the hope is that it will become more accessible, like Uber and Lyft, Vu said. Companies like Archer Aviation are in the process of developing and certifying their vehicles — perhaps in time for the 2028 Olympics.

While UAMs may eventually be unmanned, for now, they need human operators. How those human operators accomplish their missions, and what new technologies might help them, are what these CSULB students and faculty focus on.

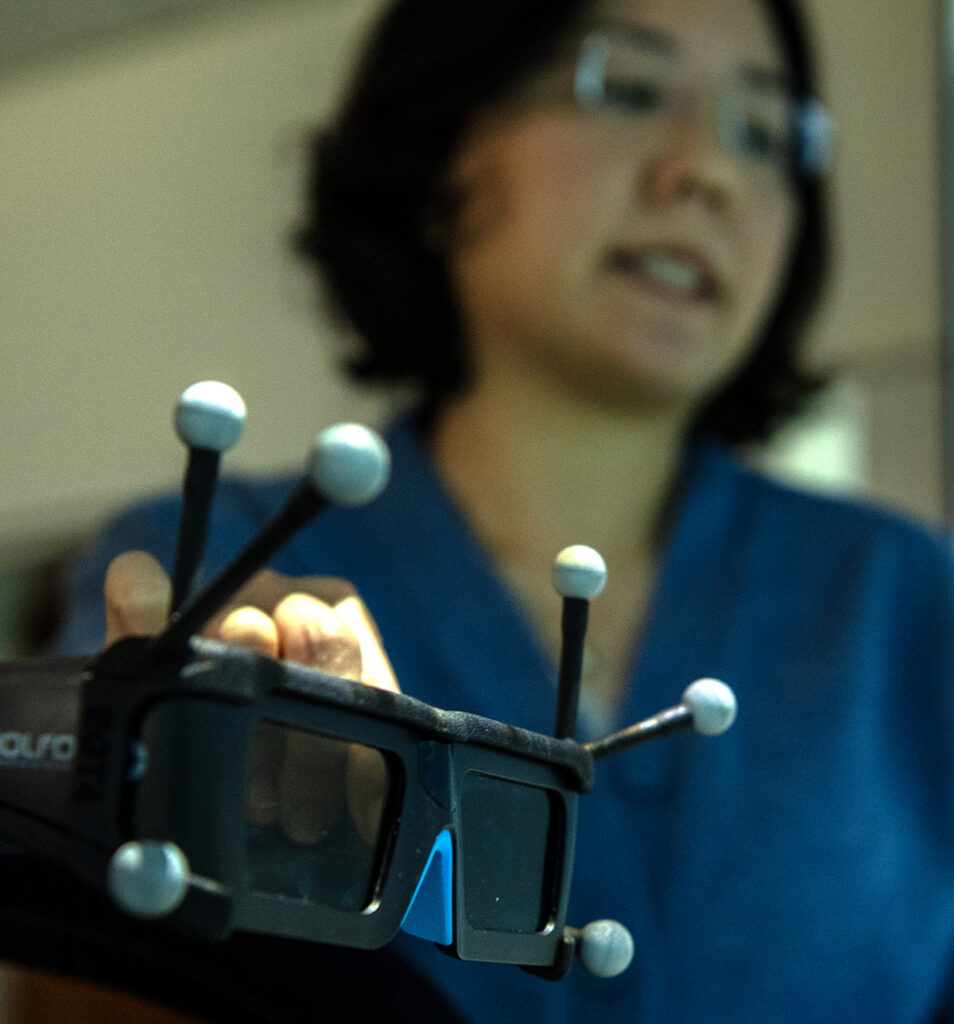

Their immersive VR system, the BeachCAVE, allows the team to test features relatively quickly. They prototype new technologies in the system and study how pilots behave. For example, as Whitney piloted the virtual aircraft at low altitude through the urban environment, he had to stick to a predetermined route. Any deviation could cause him to hit a building or end up in someone’s backyard. The researchers test how pilots respond to different cues, such as vibrations, to help them course correct.

They also study how pilots respond to battery-level indicators (similar to a fuel gauge), aircraft in the vicinity, and text and voice communication.

“To test this out in the real-world environment will probably take decades, years, maybe,” because it would require actually building the real aircraft and interfaces, said Praveen Shankar, a professor on the project. In the VR lab, “we can probably do it in a few months,” he said.

The interdisciplinary team merges different fields and skillsets. Shankar and Marayong, both engineers, help build the system, creating a VR experience as realistic to an aircraft as possible and adding technologies that alert pilots. Computer science students, like Whitney, help program the system. And Vu and her colleague Tom Strybel, in the psychology department, examine how flight operators interact with all these variables.

For students like Whitney, who was recruited to the team when a classmate discovered his knack for programming video games, the project offers a chance to work collaboratively and shape the direction of the research. “I’ve not been in an environment like that where I can have a voice on a big project,” Whitney said as he piloted the aircraft across the San Francisco Bay, navigating above car traffic on the iconic Bay Bridge.

The project began close to a decade ago, and some of the graphics look outdated. But Shankar said the team will soon upgrade their software and integrate Google Maps to achieve more realistic landscapes, including for the Los Angeles region.

Whitney navigated gracefully, avoiding a nearby commercial plane before attempting a glideslope landing, descending toward the landing pad, or vertiport, in Oakland.