This story is part of a Long Beach Post multi-part series, “Close to Home: How climate change is shaping the future of Long Beach.” For the full series, click here.

Seniors in the 17-story Park Pacific Tower in Downtown Long Beach were startled by a loud bang. Then, darkness.

The residents spent the next three days focused on basic needs—in some cases survival—without electricity. Diabetics struggled to keep their medication cool, several seniors needed oxygen machines, sewage piled up in toilets, and many didn’t have enough water to drink.

It was difficult even calling for help, as cell phones had died and landlines weren’t working. The city’s emergency workers were busy, too, responding to others in need during a series of power outages in July 2015 that started with a vault explosion a few blocks away from the building at Seventh Street and Pacific Avenue.

“We had to take care of ourselves,” said Karen Reside, who lives on the 17th floor.

The outages nearly four years ago may be a harbinger of what’s to come as the planet warms and the power grid is taxed, experts say.

The deadliest catastrophe of climate change is not fires, nor hurricanes. It is not expensive coastal homes buckling to the power of wind and water.

“It’s heat waves,” says Bill Patzert, a noted climatologist and oceanographer.

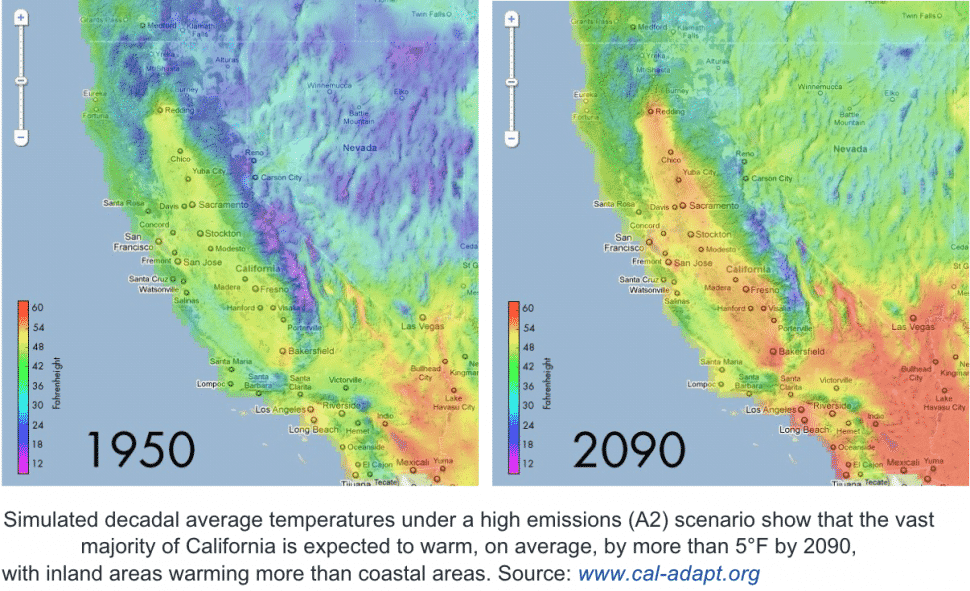

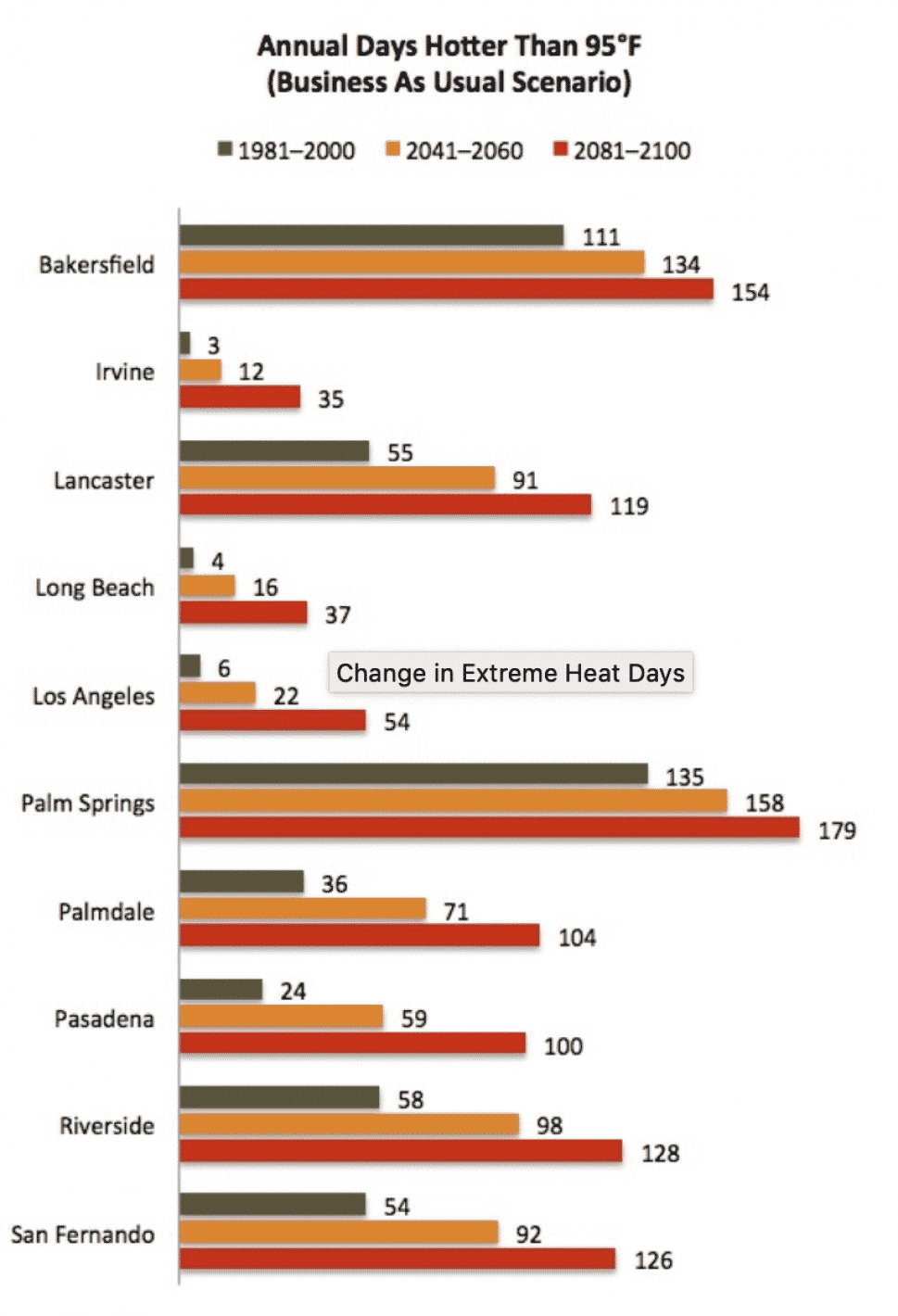

Southern California is widely known for its mild, Mediterranean climate, but even coastal cities like Long Beach will not be spared from extreme temperatures, experts say.

Places like Long Beach that aren’t used to such extensive and extended periods of heat are particularly vulnerable; swaths of the city still don’t have air conditioning.

According to data compiled for the city’s Climate Action and Adaptation Plan:

- By 2050, Long Beach will experience an average of 11 to 16 days of extreme heat per year (temperatures over 95 degrees), compared to an average of seven it experiences now. By 2100, that number will grow to a range of 11 to 37 days.

- The average temperature of the city in 2050 is expected to climb by 4 degrees; the temperature will rise by 8 degrees in 2100.

- Heat waves will occur more frequently, be more intense and longer-lasting. The heat will also be more humid, with less cooling at night.

According to the report, extended stretches of days over 100 degrees could impact air travel at Long Beach Airport, along with rail and asphalt roads, which can soften in high temperatures; the city could see an increase in tropical pathogens and parasites; and energy use will spike, taxing the power grid.

Simply put, the heat will impact more people than any other consequence of climate change.

And it kills.

The mix of heat and humidity is a particularly lethal combination, according to a study published by Nature Climate Change in June 2017, which looked at deaths caused by past heat events to predict future risk.

According to the study, around 30 percent of the world’s population currently lives in places where heat crosses the threshold considered deadly (20 excessive heat days per year). In a scenario in which greenhouse gas emissions are reduced drastically, 48 percent of the world’s population will live in places of excessive heat by 2100; in a worst-case scenario, in which nothing is done to reduce emissions, 74 percent of the population would live in such conditions, including Long Beach.

“An increasing threat to human life from excess heat now seems almost inevitable, but will be greatly aggravated if greenhouse gases are not considerably reduced,” the study concludes.

More frequent will be heat waves such as those seen in Europe in 2003, which killed roughly 70,000 people, the Chicago heat wave in 1995 that killed roughly 740 people, and a Southern California heat event that lasted two weeks in 2006 and killed 163 people (during which Los Angeles experienced the hottest day in its history at 119 degrees).

Urban heat islands

The prospect of hotter nights is especially worrisome to local officials. Coastal cities like Long Beach have usually enjoyed a respite when the sun goes down, but Patzert and other climatologists say that may no longer be the case.

The rise in humidity is one factor. The city’s south-facing coastline is another; onshore winds blow west to east, and Long Beach is largely blocked from these winds by the Palos Verdes Peninsula, which means it is naturally warmer than places like Santa Monica.

It’s also due to the fact the city has paved itself into a bigger problem: Concrete absorbs heat during the day, and releases it at night, driving temperatures even higher.

Researchers have just begun to study so-called “urban heat islands”—places of dense development, paved roads and sparse tree cover. To no one’s surprise, the most vulnerable areas are also the poorest.

In Long Beach, that means primarily North, Central and West Long Beach. The state’s Fourth Climate Assessment notes communities including Ontario, East Los Angeles and South Los Angeles will also be disproportionately affected by climate change.

A 2015 study by Loyola Marymount University looked at the tree canopy in various parts of Los Angeles County, finding a direct correlation between lack of vegetation and hotter temperatures.

The map shows the central and northern census tracts of Long Beach have less than 7 percent tree cover, with July temperatures averaging in the mid- to high-90s; the southeastern parts of the city are 40 to 50 percent green, with average peak temperatures ranging from the high 80s to the mid-90s in areas closer to the coast.

Adaptation

Efforts are underway to remedy that disparity, particularly in West Long Beach, where the Port of Long Beach recently invested $670,000 to plant 6,000 trees, primarily in the neighborhoods surrounding its facility.

A $1.26 million grant from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection announced in December will enable the city to plant at least another 4,000 trees in other areas, focusing on Central, Wrigley and North Long Beach, said Margaret Madden, a neighborhood improvement officer with the city.

“You can really see the difference in these neighborhoods,” Madden said.

The most significant adaptation to rising temperatures, however, is the one already in use: air conditioning. What used to be a luxury has now become a necessity, Patzert said.

“Without air conditioning, a great deal of Southern California would be unliveable,” he said. “Not in 2050, not in 2100, but today.”

The post-war homes in East Long Beach and Lakewood were all constructed without air conditioning. Many homeowners have upgraded with A/C, but schools have been slower to catch up.

A $1.5 billion bond measure passed in 2016 is funding the installation of A/C in phases, with Cleveland, Garfield, Kettering and Riley elementary schools and Rogers and Stephens middle schools getting upgrades this fall. All schools in the Long Beach Unified School District are scheduled to be retrofitted by 2026.

Other solutions to the urban heat island effect include incentivizing—and in some cases, mandating—so-called “low-impact development” strategies like permeable pavement, vegetation and dry wells. Though these measures are mostly intended to mitigate another effect of climate change—water shortages—the policy also promotes surfaces that lead to cooler temperatures.

Shoring up the power grid

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, a 6- to 9-degree rise in temperature would increase the demand for generating capacity by 10% to 20% by 2050, which would cost billions of dollars.

Southern California Edison officials said they have been working to improve the power grid in Long Beach, with an eye toward climate change.

“It’s very apparent that we are going to see the effects [of a warming planet],” said David Song, spokesman for SCE. “We’re going to see stronger rain storms, stronger wind storms and hotter temperatures.”

The utility has invested close to $80 million over the last four years to improve the equipment and network durability that serves Downtown and the outer suburban areas of the city, he said.

One of the key areas of focus is modernizing the power grid so that it can both give and receive energy. As more buildings incorporate renewable energy sources such as solar panels, power companies across the country are having to upgrade their systems so they can receive and store excess power.

SCE was also required by the Public Utilities Commission to complete several upgrades specific to Long Beach after the 2015 blackouts. But progress has been slow.

The first phase of work began just last year, and included the seemingly simple step of fitting manhole lids with systems so they don’t eject during an explosion.

The second phase will include replacing underground cables with more reliable copper in the Downtown system. Other work includes installation of more vault indicators and automated switches, which are more reliable in alerting officials when there’s a disturbance in the network, and more precise in telling workers where the problem is located.

“It’s like going from standard def to high def,” Song said. “Right now we have to go vault to vault to find the problem.”

The last phase involves installing current monitoring devices that will better regulate the delicate balance of supply and demand in the power system.

Preparation

Heat becomes deadly when people don’t have access to water and cool places, or don’t seek out shelter before it’s too late, officials say.

In typically warm places like the San Fernando Valley, “residents know what to do,” said Alison Spindler, a planning officer with the city who has a lead role in crafting the climate action plan.

She and others say the durability of the electrical grid is a focus of emergency personnel, particularly after the 2015 outages that left thousands of residents and businesses without power for days. The first outage sent manhole covers flying into the air after an underground explosion caused the networked power system in Downtown to go dark.

Elderly residents in high rises were trapped in buildings because elevators weren’t working, and in some cases residents had to be carried out by emergency responders. Medical equipment failed, buildings sweltered without A/C and food rotted in refrigerators.

Reginald Harrison, the director of planning and emergency response for Long Beach, said communications with Southern California Edison have improved since 2015—and many lessons were learned from those blackouts.

The city purchased 16 generators with a grant from the Department of Homeland Security and placed them throughout the city for such emergencies, Harrison said. The city also now has a mobile charging unit that can travel to various neighborhoods, recognizing that cell phones are crucial in emergencies.

Much of the preparedness efforts, however, are focused on training people to save themselves.

“In most cases, the first-responder in a major disaster is not going to be a police officer or firefighter,” Harrison said. “More than likely it’s going to be your neighbor.”

Reside, the Park Pacific Tower resident, said she and six other residents had just gone through Community Emergency Response Team training (CERT) about a month before the blackout. When the power went out, they knew exactly what to do.

“The big issues are having water, having flash lights and … having a backup generator,” she said. “We were essentially on our own for three days. Being prepared is what saved us.”