This story is part of a Long Beach Post multi-part series, “Close to Home: How climate change is shaping the future of Long Beach.” For the full series, click here.

Three of 10 shipping piers at the Port of Long Beach could be inundated with water—one of which houses a Southern California Edison substation—even in the mildest sea-level rise projections, according to an assessment risk compiled by the port.

The destruction or inaccessiblity to these and other critical assets could have significant impact on the local and national economy: the Port employs some 30,000 workers and imports and exports about $180 billion in cargo each year.

“I think that we’re already recognizing that [the effects of climate change] are a reality and we need to be planning for them,” said Heather Tomley, acting managing director of planning and environmental affairs for the port.

The local port is among just two agencies statewide that has already completed a Climate Action and Assessment Report—a relatively new requirement for agencies that receive a certain threshold of state funding. Long Beach is also in the midst of compiling its climate report; it’s expected to be finished this fall.

Experts agree: the impact of climate change on the nation’s ports will be profound. These coastal facilities are a factor in how much consumers pay for goods, and whether necessities like food, furniture and electronics are available at all.

The twin port complex in Long Beach and Los Angeles is the largest in the nation.

But in the next few decades, access roads could be covered in water; rail lines, either from heat or from ocean water inundation, would be unusable; electrified infrastructure such as cranes could stop working. The piers themselves, particularly older piers in the center of the sprawling 3,000-acre Long Beach complex, would be swallowed by sea and flood water, leaving them inaccessible to trains and trucks.

The port’s 2016 climate plan approved by the state shows which parts of the complex would be at risk, and outlines steps it could take to hold off sea level rise projected by a number of scientific studies.

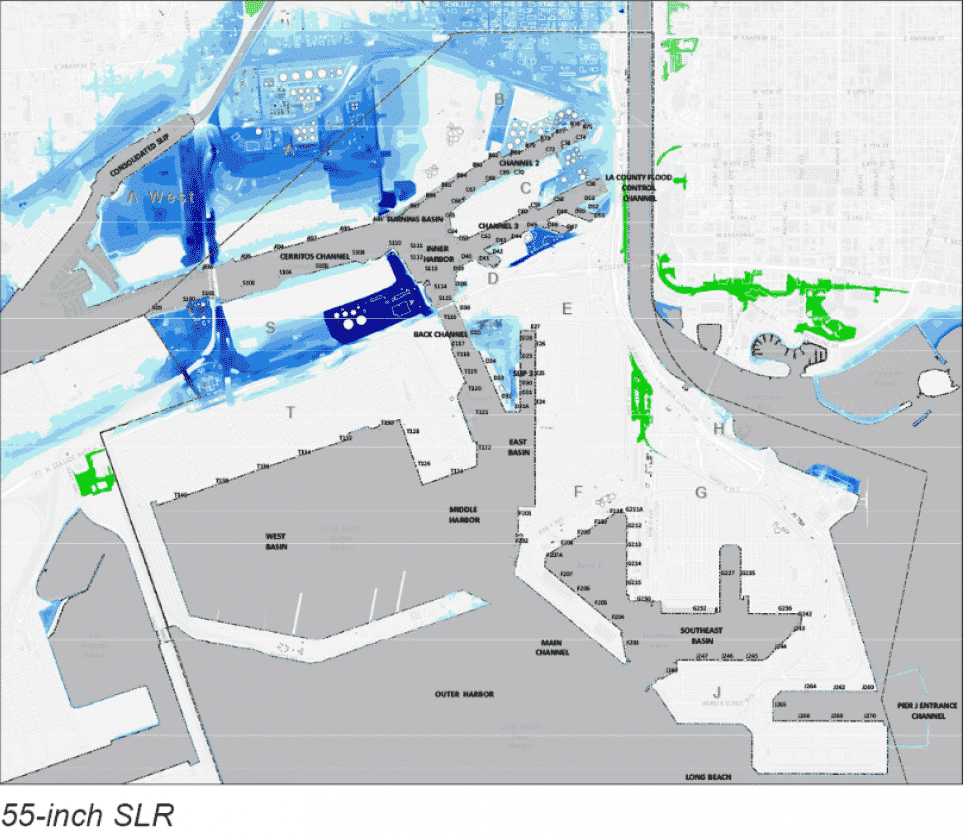

The port’s plan analyzed projected rises in ocean levels of three scenarios: 16 inches, 36 inches and 55 inches. Models also included the impacts of a 100-year storm surge, defined as a storm occurring once every 100 years, or having a 1% chance of occurring each year. However, experts say a consequence of climate change is that 100-year storms could happen more frequently and with more force.

Hurricane Maria

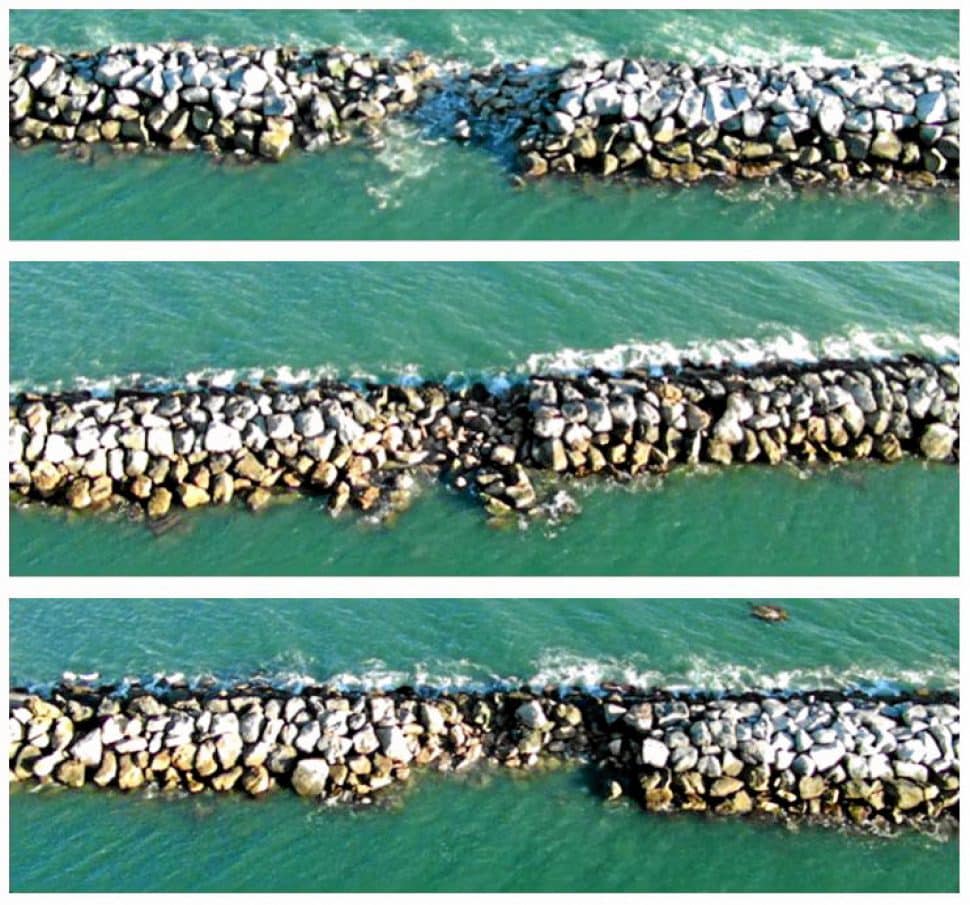

The local port got a taste of what may be in store when storm surge caused by Hurricane Maria damaged the breakwater in 2014. The breakwater—a source of much contention among surfers because it muted the ocean’s waves—is critical to protecting massive cargo ships and sensitive equipment surrounding the port.

The storm surge punched three large holes in the barrier and created a number of other smaller fissures, allowing waves to damage the rock dikes at Nimitz Road, where two barges almost sank, according to the assessment report. Access was also restricted to the Sea Launch, the Navy Fuel Depot and one of the container terminal’s rail systems.

Shipping operations were completely halted at two terminals: Total Terminals International and Crescent terminals.

And that’s just storm surge. Climate experts say rising temperatures could bring fewer, but more ferocious storms—possibly even cyclones or hurricanes—to the West Coast.

Chronic flooding will be a problem, but the more acute issue is that climate change alters weather patterns, ushering in more severe storms, said James Fawcett, an associated professor of at USC’s Price School of Public Policy.

“And the impact on the ports from these acute incidents is likely to be a matter of safety of vessels in the port, in the outer harbor and the impact it could have on the trucking business getting cargo out of the port areas and the problems it might cause for the railroads,” he said.

Fawcett said the impact of sea-level rise though could likely be navigated by port complexes like the one in Long Beach because the rise will be gradual and the ports will have time to plan for it.

“One of the things that I think is a little bit disturbing is the public tends to think of this all happening at once and it doesn’t,” Fawcett said. “It happens bit by bit by bit. I think both the ports and the terminal operators are aware of it on a monthly basis, and as things start to change, they’ll start to improve their infrastructure.”

The Los Angeles Region Report of California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment, which relies on a scenario characterized by increasing greenhouse gas emissions over time, projects a 1- to 2-feet of sea level rise by 2050, and more extreme projections lead to 8 to 10 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century.

The rise in seas and more extreme weather is largely due to thermal expansion of the water and melting of the great ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctic, as well as the disappearance of terrestrial ice in the Rockies, experts say.

Sea rise

The Port of Long Beach’s report showed various scenarios for sea-level rise and the combined impact of storm surges.

Tomley explained that the most vulnerable portions of the port actually exist in the parts tucked away from the entrance. Newer piers at the front of the complex were built higher, but older ones like piers S, D and A are lower-lying; they were built on pre-existing marshland and are more likely to be impacted by sea-level rise, storm surges and flooding.

Pier S, which houses a Southern California Edison substation that is used to provide power to what was previously the Hanjin terminal, includes a low-lying area that could serve as an entry point for rising sea water that could inundate the entire pier and compromise the substation.

The report lists a number of solutions that could be implemented that range in permanence and price.

- Sand bags placed around the substation ($65,000) is one of the cheaper options, but would require workers and sand bags to be deployable when a storm surge event is imminent.

- More permanent options, like raising and reinforcing the sea wall along the northern shoreline of the pier where flooding is projected to enter the pier, or completely relocating the substation ($10.4 million) are dramatically higher in cost.

Piers A and B, which are on the north side of the Gerald Desmond Bridge, face potential flooding from the Dominguez Channel, which in the event of heavy rainfall could funnel flood water to the port’s older back areas.

Under the worst projections (55-inches of sea-level rise) piers A and B could see inundation as deep as 16 feet. Tomley said the port, which is in the beginning stages of devising long-term solutions to prevent these scenarios, has to be aware of the consequences of whatever fixes are constructed.

“If we do install infrastructure to address those flooding issues in that area, we don’t want to build it in a way that diverts the problem away from the ports and creates a bigger problem in the neighboring communities,” Tomley said. “So, whatever we would be developing we would definitely want to be cognizant of that and that we don’t sort of install a fortress around the port that ends up causing impacts in other areas.”

Long Beach is not the only port that is taking these measures. Complexes from Seattle to New York are compiling similar reports to assess the level of exposure to rising seas.

Ports of Long Beach, Los Angeles Governing Board Approves Updated Clean Air Action Plan

Like Long Beach, the Port of New Orleans is taking steps to curb its greenhouse gas emissions in an attempt to slow the march of rising seas.

The Port Authority of New York & New Jersey is doing the same, but also implemented in 2015 guidelines for future developments at its ports to account for the impacts of climate change before projects can be approved. The Port of Long Beach similarly has required new developments to include climate change resiliency before being granted permits by the port.

While some of the most extreme projections of climate change seem far off and difficult to conceive since the port is not actively being impacted by catastrophic flooding, that hasn’t stopped it from being proactive in defending this vital economic engine.

Development at the port has historically had faster turnover than other land uses, Tomley said, and with new requirements dictating climate change resilience she is confident that the port would evolve to the challenges that climate change present.

“The 55-inch sea level rise scenario is on the upper end of what might happen 100 years from now,” Tomley said. “Before 100 years from now we will be making upgrades to the port facilities and we’ll need to make sure that when we do design for that that we’re planning for what those potential worst-case future conditions might be so we don’t put ourselves in that position.”

Fawcett said that ports and other portions of cities will benefit in the future from planning for the smaller impacts of climate change in the present. If a city can get used to responding to minor crises in the more immediate future, it will have better success when it has to respond to a larger scale weather event, he explained.

He’s confident the ports will be able to respond to climate change both because the changes that are projected by experts are going to occur gradually, and because of the financial resources of the ports and terminal operators which will allow them to fortify their operations over the coming decades.

“I’d rather be in the Port of Los Angeles or the Port of Long Beach than wanting to own property on Balboa Island,” Fawcett said. “If you own property on Balboa Island right now you’ve got a big problem.”