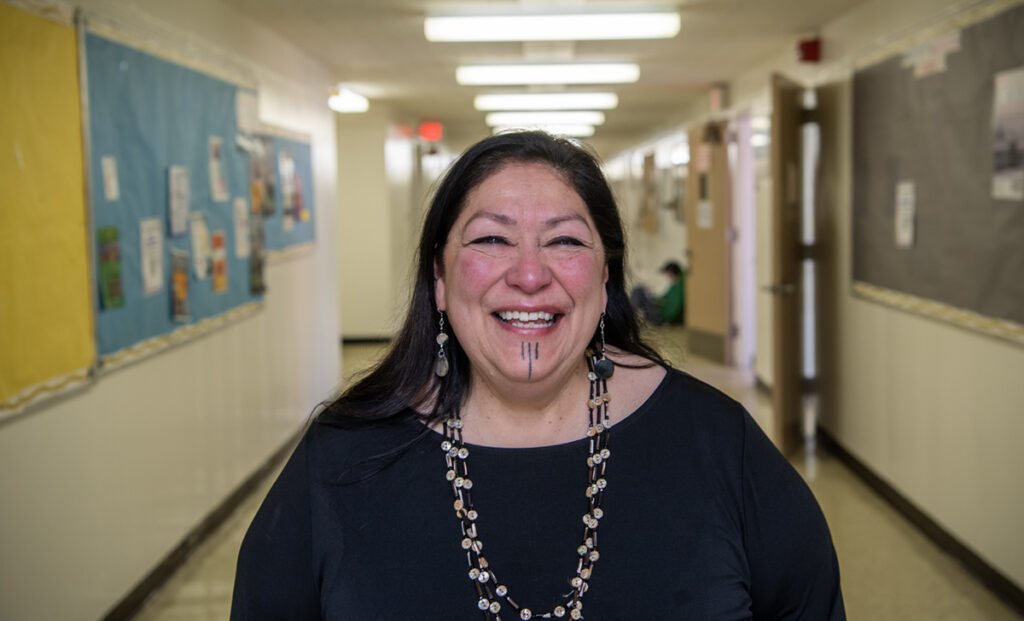

Linguist Deborah Sanchez grew up hearing only a few words in Šmuwič, an Indigenous language originating from the central Californian coast. Šmuwič words peppered her parents’ speech, giving Sanchez glimpses of the language of her heritage.

Now, as faculty and a current master’s student at Cal State Long Beach, Sanchez is devoting her life to stitching these words together, revitalizing and sharing the language, which has been dormant for decades. She sees it as “an ancestral responsibility to carry these things forward.”

Šmuwič exists in the family of Chumashan languages, spoken across the region encompassing what is now San Luis Obispo to Malibu, as well as interior land stretching toward the Central Valley. Approximately two centuries ago, close to 90 languages were spoken in California, then the most linguistically diverse area of North America, according to the California Language Archive.

Indigenous languages “did not magically cease to be spoken,” Sanchez wrote in her Cal State Long Beach master’s of linguistics thesis. Rather, she wrote, they were systematically suppressed and eliminated by settlers. “Once obliterated,” Sanchez wrote, “they were substituted in with the prevailing colonial language.”

The last first-language speaker of Šmuwič, Mary Yee, died in 1965. She left behind “remnants,” Sanchez said — an archive of hundreds of recordings. Yet they remained inaccessible to the community for years, Sanchez said.

That began to change in the 1980s. A friend gave Sanchez’s mother a dictionary of 2,000 Šmuwič words — part of linguist Kenneth Whistler’s dissertation — and she passed a copy onto Sanchez. The lexicon proved helpful, but without any syntax, Sanchez had no idea how words fit together, she said.

She earned her bachelor’s degree in sociology from CSULB in 1982 and went on to earn her law degree and become a Los Angeles Superior Court judge in 2006. Yet she continued studying Šmuwič, poring over recordings of Yee speaking the language. “Once that became available, then you can actually hear the cadence,” Sanchez said, a breakthrough. With the help of mentors, friends and family, she began piecing Šmuwič together.

In 2007, Sanchez attended a gathering of Indigenous people. A group of Mayan elders clarified that the end of the Mayan calendar, December 2012, was not the end of the world as many interpreted, but rather “entering the galactic dawn,” Sanchez said, a message which prompted her to ask how she could make the world a better place. “I prayed about it, and the answer came back: to learn the language.”

Sanchez threw herself into studying Šmuwič and began apprenticing and collaborating with others working to bring Chumashan languages back into daily use. By 2010, she had learned enough to begin teaching the language to about 20 Chumash and Indigenous community members in Santa Barbara.

Isabel M Ayala was one of Sachez’s early students and described her as a generous, compassionate teacher. “She challenges you, but she doesn’t confront you,” Ayala said.

In 2013, Ayala and Sanchez traveled to Washington DC for an Indigenous language workshop. In their hotel room, Ayala heard Sanchez speaking to her mother in Šmuwič. “That’s what I want before I die,” Ayala remembered thinking at the time. “I want to be able to have a conversation in my language.”

Learning Šmuwič transformed Ayala. “I wish I’d learned that language as a child,” she said. “It’s knowing who you are,” which “brings wellness to your spirit,” she said.

Indeed, Sanchez observed that Indigenous populations have significantly worse health outcomes and lower life expectancy than other racial and ethnic groups, as the Department of Health and Human Services has documented. She understood these health outcomes as the product of colonization and cumulative trauma across generations.

And as she gained fluency, she saw language itself as a healer, and she left her seat on the bench to explore these questions at CSULB. Sanchez’s research and other scholars have revealed the power of reconnecting to culture and heritage through words. “We can get well by our language,” she said. “If you lose everything, it becomes the biggest factor in your own well-being.”

Sanchez has composed and taught dozens of songs in Šmuwič. She leads a group of 12 women, the Chumash Dance Sisters, who have sung and danced at the Hollywood Bowl, the Aquarium of the Pacific and powwows across California.

“We are more of a community because of the language,” said Ayala, age 72 and the oldest of the dance sisters. Sanchez convinced Ayala to start dancing, despite having “three left feet,” she said. Now, Ayala is teaching Šmuwič classes, and though she can’t hold a fluent conversation just yet, she’s close.