When Jeanne Evangelista enrolled at Long Beach City College in 2018, she realized she wanted to become a librarian. But LBCC only offered a certificate or associate’s degree in library and information sciences, so Evangelista had to pursue further education elsewhere to realize her career goals.

That may change with Long Beach City College’s announcement of its first four-year degree, a bachelor of science in library and information science, set to launch in fall 2027 and fill an “educational vacuum” in the field and region, LBCC Professor Colin Williams said. The program aims to prepare students to enter the workforce immediately as well as create an affordable path to librarianship.

California offers the largest inventory of library certificate programs in the nation, according to the Association of College and Research Libraries. Yet there are no bachelor’s programs in library science in the state; LBCC’s will be the first.

That void has forced students like Evangelista to pivot to other disciplines to complete their bachelor’s degrees or leave the state to earn a bachelor’s in library science.

Even nationally, few such bachelor’s programs exist, Williams said, as the library science field has shifted its focus to master’s degrees, a requirement to become a librarian. Usually, an associate’s degree is necessary to become a library technician.

The dearth of bachelor’s programs reflects a gap in library science training, not the utility of the degree, said Walter Butler, Director of Library and Information Services at Santa Monica College. Many library jobs still require bachelor’s degrees, even if not in library science (reflecting the scarcity of those programs), which results in a library workforce without the specific training a bachelor’s in library science could provide, Butler said. LBCC’s program is “going to strengthen the library profession,” he said.

The new program’s course of study is designed to be responsive to the rapidly changing digital landscape and prepare students for career pathways in both traditional and non-traditional library settings, said Williams, curriculum chair of LBCC’s library science program.

The program will teach students about data, archives, catalogues, and digital tools and resources, including applications for large language models. Students will also need to develop the soft skills necessary to meet the diverse, growing needs of library patrons, Butler said.

Legislation passed by Govs. Jerry Brown and Gavin Newsom paved the way for California community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees. Yet, California State University campuses have blocked more than a dozen of these degrees, arguing they duplicate CSU programs, according to EdSource.

As part of the application to the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, Williams had to show the program does not compete with CSU or University of California offerings.

Williams also had to demonstrate labor market demand (an analysis projected nearly 600 unfilled library science jobs statewide, annually) as well as earning potential (library science job seekers with bachelor’s degrees may earn $23,000 more than those without).

Critically, he had to show that students wanted the program. Of 101 LBCC library science students surveyed, 89% reported being very interested in a bachelor’s degree program.

Evangelista said she would have jumped at the opportunity to pursue a bachelor’s at LBCC and save money. Instead, she transferred to Cal State Long Beach and majored in history, before undertaking her master’s in library and information science at San Jose State University.

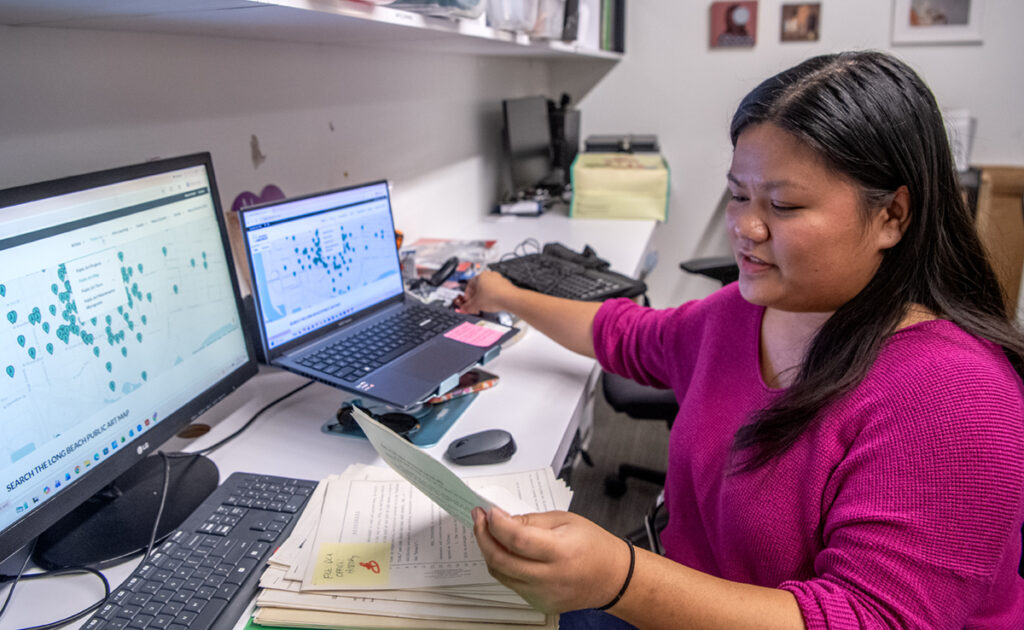

Now, Evangelista oversees LBCC library and information science interns at the Arts Council for Long Beach. Evangelista said her students, who help digitize art and documents, would benefit from archival and collections education, as well as skills they can apply outside of a traditional library setting.

One of her interns, current LBCC library science student Marya Long, said she would have “stuck with the associate’s degree,” even if the bachelor’s were available. But she would take upper-level library science courses “a la carte” to strengthen her training.

For Stephanie Pacheco, the affordability and flexibility of LBCC bachelor’s program is a “huge relief,” she said. Pacheco had almost completed her bachelor’s in theater when “my need to pay rent superseded my academic ambitions,” she said. She earned her associate’s at LBCC in 2019 and became a clerk at Mark Twain Library in Central Long Beach but put further education on hold. Now, “finally at a point” of studying to become a librarian, she is considering LBCC’s bachelor’s.

Lee Douglas, LBCC vice president of academic affairs, said the college plans to strengthen the hands-on training library students complete through internships, as well as explore partnerships with other institutions for further education, some of which are materializing.

Anthony Chow, director of SJSU’s School of Information, has proposed that credits earned through LBCC’s bachelor’s program count toward SJSU’s master’s in library science.

“There is a long-standing controversy in the field about whether professional librarians need a master’s degree, and the answer is yes,” said Chow, who leads the California Library Association. A bachelor’s shouldn’t replace a master’s in library science, because that would dilute salaries and expertise, Chow said. Rather, LBCC’s program will create a pipeline for librarians and information experts.