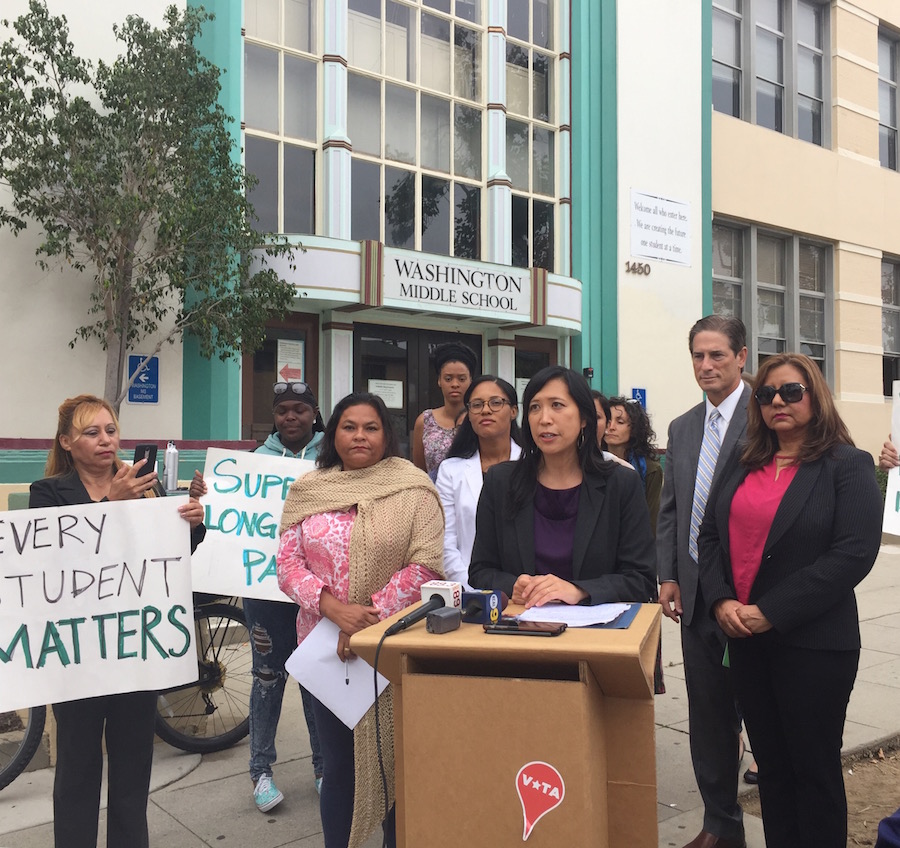

Angelica Jongco, senior staff attorney for Public Advocates, speaking about the appeal submitted to the California Department of Education. Photo: Jason Ruiz.

Community organizers, parents of Long Beach Unified School District (LBUSD) students and their legal representation stood outside the steps of Washington Middle School Thursday morning where they organized a press conference to announce that they would again challenge the funding allocations of the district, this time appealing to the California Department of Education.

The appeal comes weeks after the district responded to the groups’ initial complaint filed in April where they alleged that LBUSD had inappropriately allocated funds intended for high needs students—defined as foster youth, low income and English-learners under the law—by spending the dollars in a districtwide fashion.

A law passed in 2013 changed the way that school districts are funded. Known as the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), districts are granted a generic pot of money based on attendance and grade levels of students, but are also given additional funding for disadvantaged or high needs students. LBUSD passes a three-year budget known as the Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP) which allocates these dollars to schools in the district.

In the original complaint, the group, which includes Children’s Defense Fund California and Public Advocates, a non-profit law firm based in the Bay Area, alleged some $40 million in LCFF funds had been misappropriated.

Standing in front of the school’s main entrance, Public Advocates Senior Staff Attorney Angelica Jongco announced that the public had scored some small victories since April with the district agreeing to restructure its budget, removing about $17.8 million in LCAP allocations that had been earmarked to pay for teacher’s salaries and basic technology.

It also scored a victory in transparency, she said, as the district is now providing much more detailed explanations of how this money is being spent.

However, she said that the group’s appeal to the state board of education rests on the fact that nearly $30 million in LCAP funding is being directed toward common core textbooks and instructional aides.

“The formula takes into account that there are basic, essential, core services that every student should get throughout the state and those services should be funded with the base amount that all students generate,” Jongco said referring to the district’s plan to spend about $17 million of LCFF funds. “But really, LCFF is about providing something more for students with the highest needs to really make a difference. To close that achievement gap, those funds should not be used to provide those basic services that should have been provided under the law all along.”

RELATED

Long Beach Unified School District Accused of Misusing Funds Earmarked for Disadvantaged Students

The district has contended that because such a high number of its students—roughly 70 percent—fall into categories that would qualify for additional LCFF funds, that districtwide expenditures fall in line with the spirit of the law.

In its answer to the complaint filed in April, the district justified the $17 million expenditure on textbooks saying that “the District selected material that would both improve and increase its services to its unduplicated pupils and anticipates that the new materials will have a neutral effect on non-unduplicated pupils”.

In other words, the books were chosen with high needs students in mind in an attempt to close the achievement gap between them and higher performing students. It justified expenditures on teacher salaries by stating that staying competitive in retaining talented faculty members has an impact on learning district wide but still chose to pay for those expenditures from other funding sources. In regard to instructional aides, the district’s response said it would work to develop a job classification to better show that the positions have been developed to work with the high need population.

District spokesperson Chris Eftychiou said the LCCP meets or exceeds the state requirements and the spirit of the law reiterating that with 70 percent of the population qualifying as high need the LCCP’s whole-system approach benefits all students.

Eftychiou added that with the state department of education set to release performance data next week it would become clear that the Long Beach approach was working as it will reveal greater growth in math and English last year than the state’s other large school districts. He said that the improvements were witnessed across all subgroups, including high needs students, with some LBUSD schools closing achievement gaps by 50 percent or more.

“The bottom line is that Long Beach is getting significantly better results than our counterparts elsewhere in the state, but Public Advocates disagrees with how we’re getting there,” Eftychiou said.

“So the question is, at what point do such complaints become an attempted end run around local control, when large law firms from well beyond Long Beach continue to assert their vision of how we should be serving our local students?” Eftychiou went on to say. “When Governor Brown successfully pushed for local control of spending in our public schools, he wanted exactly what Long Beach is doing.”

Brown pushed for the change in local funding in 2013, stating that “Equal treatment for children in unequal situations is not justice” when he revealed his intentions to redistribute funding based on the different “real world situations” faced by districts throughout the state.

The parents on hand at the press conference, some of whom are complaintants in the legal challenge, want exactly that: justice.

Marina Sanchez, whose autistic son graduated from Millikan High School, said her son was arrested when he attended Long Beach Polytechnic High School for behavioral issues. Sanchez said it took a lawyer to get him transferred to Millikan where he was able to find the services that helped him graduate.

Lupe Luna, who has three school-aged kids in the district, said there’s a lack of equity in the district that has affected her children as well as many others across the city. She attributed the low achievement levels to funds being spent in the wrong places and a lack of academic support for children like her own.

“I’ve observed and personally experienced the most basic needs such as lack of intensive programs in reading, math, writing, and English and language arts,” Luna said through a translator. “I have seen inadequate tutoring programs for which my children don’t qualify because the limited slots are for students with extreme needs or for enrichment of students who are more advanced.”

As the appeal winds its way through its next chapter of legal hurdles some members of the community remain at odds over the budget. An answer is expected within the next 60 days after the state investigates the appeal but one parent is troubled over how this issue got to this point.

Martha Cota, a parent and the executive director of Latinos in Action-California, said this problem could have been resolved if the district had heard the parents’ voices when they expressed these concerns prior to seeking legal assistance.

“It’s unfortunate that we’ve gotten to this point where we need to have lawyers come speak with us in order to get heard,” Cota said. “We don’t understand why there’s so much money being spent, so much time being spent, when we could resolve this with the parents’ input.”