This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

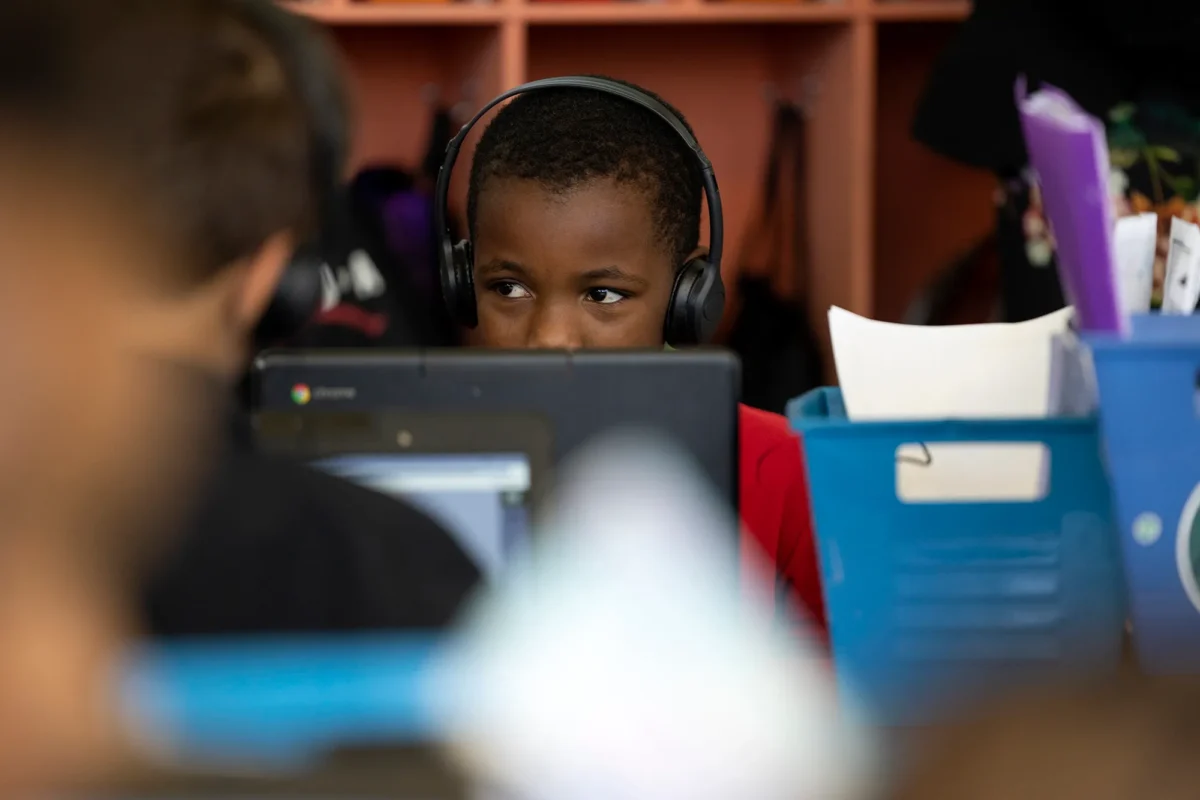

For every aspect of a student’s life, there’s a tech company trying to digitize it. Inside the classroom, online tools proctor exams, create flashcards and submit assignments. Outside, technology coordinates school sports, helps bus drivers find the right route and maintains students’ health records.

California has a number of laws aimed at protecting children’s data privacy, but those laws have exceptions that allow many tech companies to continue packaging and selling students’ personal information.

This year, Assemblymember Dawn Addis, a San Luis Obispo Democrat, is carrying a high-profile state bill that would add new protections for students. She says it’s important, especially as the Trump admin is trying to collect data about California residents’ immigration status, gender identity, and their use of certain public benefits.

Historically, California has been a leader in data privacy. In 2014, California passed a landmark student privacy law that prohibited technology companies from selling students’ data, targeting students in advertising, or disclosing their personal information. Then in 2018, the state passed another unprecedented bill that required all companies give California users certain privacy rights, such as a chance to opt out of data collection and delete some of their information.

But as technology evolved and proliferated, privacy laws repeatedly fell short in protecting California’s students — at the same time that the federal government has tried to collect increasing amounts of personal information, Addis said.

Her bill would restrict how AI companies use student data and create new data protections for college students. Some of Sacramento’s most powerful players are paying close attention to the measure, including the California Labor Federation, which supports the bill, and the California Chamber of Commerce, which opposes it. Combined, these two groups spent nearly $8 million on campaign donations to state legislators or other political activities in 2024, according to the CalMatters Digital Democracy database. TechNet, a trade association that represents many of the most powerful tech companies, also opposes the bill.

The proposal, Assembly Bill 1159, would close certain loopholes in the state’s 2014 education privacy law, but experts say it may not be enough to prevent companies from selling students’ data.

A privacy expert struggles to keep her information private

Jen King is a privacy and data policy fellow at Stanford’s institute for AI, where she studies the tricks that companies use to gather users’ data and prevent them from opting out, sometimes known as “dark patterns.” In her personal life, she’s vigilant about avoiding online data tracking and maintains a landline in her Bay Area home to avoid giving out her cell phone number.

King doesn’t want her children’s information available online or for any company to sell, though sometimes it happens before she can stop it.

In the fall, King got an email about a platform called TeamSnap, which her 12-year-old son’s cross country coaches were using to manage the team’s roster. The company wanted her information, including her name, date of birth, gender, email address, and phone number. Once she logged in to the platform, she could see some of her son’s information, such as his name, email, and date of birth, were already listed. Photos and personal information from all of her son’s teammates were also available for her to see.

“I was super irritated,” she said. “You don’t need my birth date — I’m a freaking parent.” She acknowledged some personal information could be useful for a coach but said that other questions seem designed to help the platform sell information to data brokers and ultimately, to advertisers.

Her 17-year-old son’s data is also on TeamSnap, she later learned, because his robotics team uses it. This month, when King tried to show CalMatters her TeamSnap account, a pop-up appeared, asking her if the company could track her activity across other apps and websites.

Federal law requires companies to get parental consent before knowingly collecting or selling data from children 12 and under, but once a child turns 13, their data is generally treated much like an adult’s information, especially when that child is interacting with tech platforms outside of school. TeamSnap’s privacy policy says it doesn’t knowingly collect personal information about users under 13 “without express parental consent,” though it says in some cases a team or organization may provide information on behalf of the child.

The policy also says that TeamSnap has “not sold the personal information of any consumer for monetary consideration” in the last 12 months, but that its “use of cookies and other tracking technologies may be considered a sale of personal information under the CCPA (California privacy law).” Information sold to advertisers and marketers included users’ names, contact information, purchase history and geolocation, the policy says.

California privacy law specifically requires certain large for-profit companies to get consent to collect data from anyone under 16. Often, consent happens when a user first opens a website and a pop-up appears, asking if the website can sell your data or track your cookies.

If a teacher, coach, or other authority figure tells a student that they have to use a website or an app, then the student cannot realistically opt out, King said. They may be too young to understand how to opt out, she added. “Most 15-, 16-year-olds don’t have any idea what this is about.”

Even older college students may have little agency in the technology they use, especially if it’s required for class or residential life. At Stanford, for example, King said her undergraduate students are often required to create Facebook accounts for student groups.

The same is true for parents. King said she reluctantly gave TeamSnap her personal information, including her name, email, date of birth, and the landline number for her home, because it was the only way to get updates about her son’s team.

How companies get around California’s education privacy laws

In 2014, California became the first state in the country to regulate education technology companies directly, but being first comes with its drawbacks. “We didn’t have examples of what best practice was,” said Amelia Vance, the president of the Public Interest Privacy Center, a nonprofit organization. The law only applies to products that “primarily” serve K-12 schools and that are designed and marketed for students.

Many tech companies argue that their products aren’t primarily intended for students or at least that they were not designed or marketed that way. The language-learning app DuoLingo, for example, has a version for schools, but the app is also popular for adults. Apps or technologies serving extracurricular programs or sports teams can claim they weren’t designed and marketed for the classroom, or that their use isn’t mandatory, said Vance. “You have this sort of black hole where there haven’t been protections.”

Addis’ bill expands the number of education technology companies that fall under the state’s student privacy laws, but the language is murky when it comes to apps or online services used outside of class.

In the case of TeamSnap, Addis’ communications director Alexis Garcia-Arrazola said the company would “most likely” fall under the scope of the bill if its technology is marketed to schools, if schools direct students to use it, and if the sports team is sponsored by the school.

Public records show that Piedmont Unified School District in Alameda County, Tamalpais Union High School District in Marin County, and Santa Monica Malibu Unified School District all purchased versions of TeamSnap, but only the Santa Monica Malibu district responded to CalMatters questions about any privacy restriction imposed on the company. Brandyi Phillips, the chief communications officer for the Santa Monica Malibu schools, said the district has an annual subscription with TeamSnap, which is only available to sports staff and parents. She said there’s an agreement with the company “to protect District information and to prevent unauthorized access” but did not clarify if that agreement prevents the district from selling students’ information.

Berkeley Unified School District, where King’s children attend school, did not respond to CalMatters’ questions about any contracts, purchase orders or agreements with TeamSnap.

Locally, school districts and colleges have the power to negotiate the privacy terms of any contract they make with a technology company, but many websites and apps offer free versions that a teacher or coach might recommend without getting formal approval from their district.

Last year, the California State University system signed a nearly $17 million contract with Open AI, the company that operates ChatGPT, including an agreement that the company will not train its models on student data. Advocates for Addis’ bill say the same privacy restrictions should apply to any AI company with access to California student data, regardless of whether the company has an agreement with the student’s school district or college.

Are privacy laws getting stricter or looser?

Addis’ bill comes as privacy laws in California and across the country are in flux. In 2020, California voters approved a proposition to create a new state agency to enforce data privacy rules and regulate the businesses that collect data. Advocates for the proposition contributed over $6.7 million to the campaign, compared to just over $50,000 contributed by the opposition, according to state data. The state agency that the proposition formed, now known as CalPrivacy, released new rules this year, restricting the use of automated decision-making technology, such as the use of AI to make admissions or hiring decisions. Those rules were originally stricter but businesses, lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom pressured the CalPrivacy board to water them down.

In Washington D.C., Congress is considering changing federal law to limit how companies interact with children under 17. Separately, Congress is considering a bill that would require social media companies to prevent and mitigate children’s sexual exploitation, bullying, and self-harm. California Attorney General Rob Bonta is concerned that one version of the social media bill contains language that could erode existing protections in California law.

Bonta’s office is responsible for enforcing many of the state’s existing privacy laws. In November, he said the state worked with Connecticut and New York to reach $5.1 million in settlements against Illuminate, an education technology company that uses data to track and evaluate students’ progress, such as their testing scores and developmental milestones. The company had a data breach, exposing “sensitive information” from over 434,000 California students, the state attorney general’s office said in a statement.

It was the first time California successfully went after a company for violating the state’s landmark 2014 education privacy law.

To increase enforcement, Addis’ bill contains a new provision — the right for students and parents to sue tech companies in certain cases for privacy violations. Business and technology groups have opposed the bill, arguing that the new regulations and the right to sue would stifle investment in AI-powered learning tools.

King said that giving consumers the right to sue is often the only way to increase enforcement. Otherwise, the onus is on individual consumers to find concerning practices and try to opt out.

Despite being an expert in data privacy, King said that she struggled at first to figure out how to delete her TeamSnap account, only later to discover that she needed to send an email to the company. She laughed at the irony, since it’s these kinds of dark patterns in user design that fuel part of her research.

In academia, the strategy of trapping customers is sometimes called the “roach motel,” she explained, a reference to a popular television ad from the late 1970s for a cockroach trap.

“You can check in,” she said, “but you can never check out.”

CalMatters reporters Khari Johnson and Ryan Sabalow contributed to this story.