Students at Marshall Academy of the Arts work on a robotics project in 2014. Photo: Brian Addison

The confirmation process of the new United States Department of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos yielded weeks of protests, contentious questioning from United States senators and plenty of despair and anxiety for parents and students across the country.

DeVos, a billionaire Republican donor who has no prior experience in public education, was confirmed this week in a historic vote that required the vice president to break a 50-50 tie for the first time ever for a cabinet nominee. She has been reviled for her views on charter schools, for profit institutions, the role government should play in providing for students with disabilities and even the need to have guns on campuses in the event a bear should appear.

Now that she’s at the helm of the country’s educational vessel, what does that mean for Long Beach, a city that has prided itself on its education system, and has even set a national precedent for providing greater access to postsecondary education to all students through the College Promise?

The city’s educational leaders are not immune to the doom and gloom outlook of the DeVos confirmation. Long Beach Community College District Trustee Sunny Zia called Tuesday’s senate confirmation of DeVos an “assault on public education” and Long Beach Unified School District Superintendent Chris Steinhauser called her unqualified to step into that position.

State Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell, who leads the assembly’s education committee and is an educator himself, said that public education is an American value, one that has made America great as it serves as the great equalizer. DeVos, he fears, will use her office to harm public education, stating that destroying education was merely a hobby to DeVos, and ran extensive one at that.

“We have a secretary of education who has quite possibly never set foot in a public school,” O’Donnell said. “She’s more interested in school choice than she is school quality. The way that I look at her and people who have her type of thinking, she wants to use schools to tear apart the fabric of America and sew it back together to reflect her conservative social view.”

Raw emotion aside, most of what could happen in the DeVos era is speculation at this point as she’s only been in office for a little over two days.

But her track record in Michigan, where charter schools advocated by DeVos and her family have led to sagging performance by students who attend them, has administrators nationwide worried their school systems could be next.

Multiple accounts of how her advocacy and the policies that she’s helped install over the past 23 years have led to widespread collapses in the public school systems in the Wolverine State.

Through advocacy—and high-dollar donations to local politicians—DeVos was able to advocate for school choice, a voucher system that would have re-appropriated federal funds meant for students in poverty and the deregulation of for-profit charter schools as well as the abolition of the cap restricting the number of charters allowed to operate in Michigan. However, her ability to expand that on a national scale may be limited.

Steinhauser said that a voucher program, for instance, would require states to apply for and provide matching funds for it to work, something he said the state leadership hasn’t expressed any interest in. LBUSD has an annual budget of about $850 million and of that he estimated about six to seven percent comes from the federal government. The district does receive money for each student based on daily attendance but those funds come from the state.

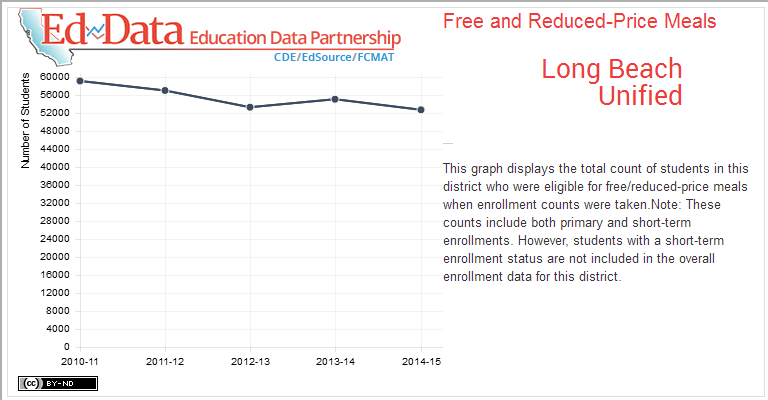

While declining slightly over the past few years, the number of students qualifying for free or reduced lunch still makes up the majority of LBUSD enrollment.

Title I funding, which is allocated to schools that have 75 percent of students qualifying for free or reduced lunch, makes up about $24 million currently, a figure that has dropped consistently over the past seven years, Steinhauser said. The school also receives Title II funds meant to address teacher and principal quality as well as funds for disabled students amounting to about $50 million to $60 million annually.

His concern is that those Title I funds, which have been rumored to be the source of a voucher program if congress adopts one, could continue to shrink.

“That amount of money was $42 million,” Steinhauser said. “Every year it has been going down based on congress not adding any more money to it and more kids in the nation are qualifying for free or reduced lunch so you have to take the same amount of money and divide it by more kids.”

Still, Steinhauser said that even if the federal government decided to institute some extreme policy the state would likely exercise some civil disobedience. And if Trump tried to defund the state it would likely be tied up in the courts for years.

“The government has zero influence on telling us what we have to teach,” Steinhauser said. “Anybody, President Trump, could say they’re going to get rid of common core; they can’t. There’s nothing to get rid of because they don’t have control over that.”

However, due to the uncertainty surrounding federal budget allocations he has proactively instructed LBUSD board members to reduce spending to offset any potential cuts that could exceed the current pattern that Steinhauser said has been roughly a cut of $2.5 million annually.

Seventy percent of students in the LBUSD qualify for these funds, and the allocations to schools can vary. Schools like Jordan High School and Cabrillo High School could take substantial hits if Title I funds were redirected or decreased as they currently get about $1 million each annually.

LBUSD Board Member Megan Kerr said the budgets for schools in the city are already being affected as they’ve implemented Steinhauser’s instruction to trim in preparation for potential budget gaps in the future.

The budget, which is usually written three to five years out, has been structured to use about 80 percent of funds, Kerr said. This could translate to one fewer science teacher, less library time or less computer techs as the district strives to hire positions it feels it can sustain in upcoming fiscal years.

“It just means that there’s not quite the amount of money in the school’s budget for programs that they want to do at the local level,” Kerr said. “Every school has less to do stuff like that now. It might look different at different schools depending on the needs.”

While Long Beach, and on a larger scale, the state of California might be insulated from any dramatic changes to education policy at the federal level, she said there are counties and states nationwide that would be open to policies championed by DeVos. As a mother and administrator of education, Kerr worries about the implications of policies that could touch a generation of students, if not more.

“My concern is that to small counties and school boards across this country that this now becomes an open invitation to do those things that I think are most damaging,” Kerr said. “Whether it’s vouchers, whether it’s bringing in faith-based education and paying that with public dollars […] We already have issues with school boards that want to do that, and now there is this blanket permission.”

That concern is not constrained to the K-12 circles as eventually those students will enter into post-secondary education. If Long Beach City College were to suddenly take on a surge of students who don’t meet prerequisites in math or English due to fundamental changes in lower levels of education, LBCCD Trustee Vivian Malauulu says the school would currently not be able to accommodate it.

“Long Beach City College right now is not prepared for a gigantic influx of students who are not prepared in terms of our remedial classes,” Malauulu said. “Obviously we’ll see it coming down the pipe when we start getting kids from the high schools who are not passing high school exit exams or are not meeting all the requirements for college.”

Her primary concern though is the way that students and the college itself can access federal money. According to a 2014 self evaluation report completed by the college, about 40 percent of students receive a federal Pell Grant which can be used to pay tuition, fees and purchase books among other things.

Nearly 80 percent of LBCC students received either a tuition fee waiver or a federal grant to assist with the cost of attendance in the 2012-2013 school year.

While Congress would ultimately hold power of student loan interest rates, there seemingly has been little opposition or deviation between the policies promised by the White House and those being pushed by members of congress and the president’s cabinet. Raising rates, especially on the more affordable federally subsidized loans that allow students to not accrue interest while in school, could make a college education even more expensive than it already is.

“I think student loans are astronomical,” Malauulu said. “I think the cost of post-secondary education is ridiculous and she’s going to make that gap bigger because she comes from money and she doesn’t understand the plight of college students. She will never be able to sympathize and understand what the average American child goes through.”

DeVos was grilled on this point during her senate confirmation hearing, with Senator Elizabeth Warren hammering DeVos for her lack of understanding about college costs as her wealth has insulated her and her family from having to take out student loans, and for her lack of experience of having her hands on the levers of a budget as large as the federal student loan program.

The new secretary also failed to take a stance on whether she would allow these federal dollars to flow into for-profit universities, a practice that is currently barred unless institutions can show they meet minimum requirements for debt-income ratios of their graduates.

The gainful employment rule, and DeVos’ failure to take a stance on it, has Zia worried that the department’s policies going forward will be more focused on the deregulation of access to federal funds by those for-profit institutions instead of increasing access to higher education for poor students.

“The number one thing is they’re not going to crack down on these for-profit colleges,” Zia said. “They’re not going to give any kind of support for public education on the front of making it more accessible and removing barriers.”

A common thread among Long Beach educators has been a willingness to stand up and fight back against policies they view as wrong, immoral or even unconstitutional. Both LBCC and Cal State Long Beach have recently pledged to protect undocumented students from deportation and at the state level. O’Donnell introduced legislation this week to ensure that California students with disabilities have access to preschool education, adding that future efforts would be made as policies are presented by the Feds.

The same resolute front that worked to establish the network of education that has helped so many students in Long Beach matriculate from grade school to the university level may now be needed to defend that very framework from future policy changes that could work to derail it.

“We have a great program in Long beach,” Zia said. “The [college] promise has given so much hope to so many students and has made it so accessible and so attainable for them to go to college. I think that we can all agree as educators and lawmakers that we’re going to put everything we have into this.”