Singrid Dueñas used to think homeschooling wasn’t such a bad idea. In an age of campus shootings, it meant having her kids closer and safer.

Now, as Long Beach schools are in the second month of their coronavirus closures, the single mother of four has realized that the task at hand is more daunting than she imagined—with no end in sight.

“I don’t like it because the kids are not getting the education that they need,” said the 52-year-old Honduran immigrant, who lives in North Long Beach. “They become lazy and I have to tell them: ‘Do your work, do your work.’”

Dueñas’ challenges are compounded by the fact that she lacks the technological know-how to help her children with their schooling since classes moved online. Until recently, the family did not even have an internet connection for laptops provided by the schools.

The Long Beach Unified School District estimates that, like the Dueñas family, 10% to 12% of their households did not have internet access before the pandemic struck. Cal State Long Beach education professor William Jeynes says that even among families who do have access, many may not have the digital literacy to accomplish much more than a Google search or browsing social media.

“For a lot of people it doesn’t go much beyond that,” Jeynes said. “They may not know the internet sufficiently to be able to help their kids.”

Jeynes says about 60 million Americans do not have adequate access to the internet—a group that includes low-income and immigrant families in both rural and urban communities.

If there’s a silver lining to the pandemic, Jeynes said, it may be this: “It will force us to go the extra mile in making sure that our most vulnerable children have a higher degree of computer literacy and internet literacy than they otherwise would have.”

School district officials said they do not yet know exactly how many students have been turning in their online assignments. LBUSD spokesman Chris Eftychiou said the district is looking into collecting feedback from teachers on student engagement.

When LBUSD closed its schools March 16, Dueñas thought she could take her children to the library, but that plan fell through when she found out all city libraries were shuttered as well.

With libraries closed, the district stepped up efforts to provide laptops to students who did not already have them. As part of that push, a handful of middle and high schools became distribution sites for the laptops a week after campuses closed. Some of them were loaners pulled from classrooms, while an older assortment were given to the students to keep.

In all, more than 10,000 laptops were provided after the schools were shut down, Eftychiou said. That’s on top of about 20,000 older laptops that were given to families last fall, with more available today for families in need. The district also is underwriting up to 5,000 mobile hotspots that families can use for six months at home with their smartphones to connect devices to the web.

Dueñas and her youngest daughter, an 11-year-old who attends Jane Addams Elementary, were among the thousands of families who lined up at Jordan High School in late March to borrow a laptop.

Her older daughter, a 17-year-old enrolled at a local charter high school, was also able to borrow one from her school, while her youngest son, a 12-year-old who relies on Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs, at Perry Lindsey Middle School, had been given a laptop before the pandemic.

But they still didn’t have an internet connection for assignments until weeks after the school closures when a Post reporter helped them get one through a free, 60-day promotion offered by Charter and to which the district was directing families.

Beyond technological challenges, family dynamics at home can also create obstacles to learning.

Dueñas said her older children sometimes are able to help the younger ones. But it doesn’t work, she said, when they become stubborn or refuse to listen to each other.

For example, when Dueñas asked her eldest son, who is 18, to help his little sister, he obliged but refused to turn off the television playing in the background, which was distracting her.

Even when he tried to be nice and asked the young girl about her life goals, she wouldn’t respond honestly, Dueñas said. “She was thinking it was a joke.”

When asked whether being at home was hurting her motivation and concentration, the girl said simply, “maybe.”

In mid-April, school district officials sent letters to parents detailing homeschooling guidelines for students, including the amount of time they are expected to participate each day, depending on their class load. Knowing that parents would need time to adjust to this shift, the school district waited until April 23 to mandate participation.

The guidelines are part of the school administration’s “do no harm” philosophy for students who may be lacking the resources needed to learn at home. This includes abandoning report cards for elementary school students and pivoting to pass/fail grades for middle school students and credit/no credit grades for highschoolers—a move that recently received push back from high-achieving pupils.

“Our focus is on excellence and equity and that means excellence for every single student,” Deputy Superintendent Jill Baker told the Post during a recent live chat.

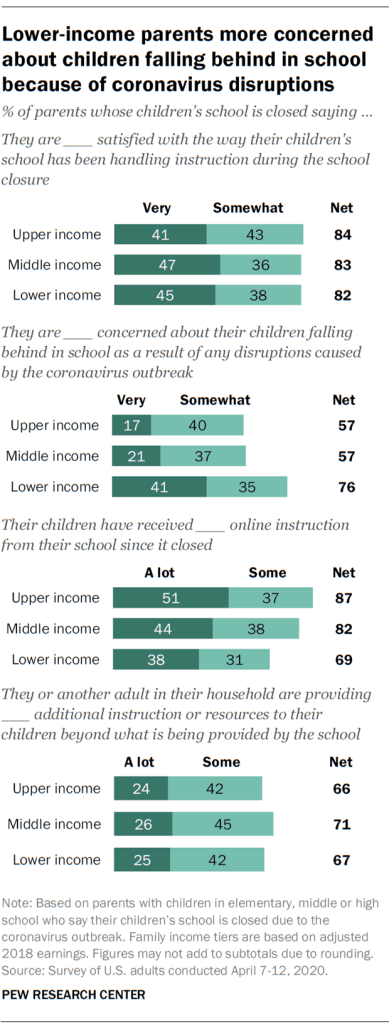

A Pew Research Center survey last month found that two-thirds of parents with children in K-12 schools are worried about them falling behind, with lower-income parents expressing greater concern.

According to the survey, income level also affects the amount of instruction parents—or other adults in the household—are able to give, in addition to what the school provides. The survey found that 51% of upper-income parents say their children have received substantial online instruction since their schools closed because of COVID-19, compared to 38% of lower-income parents.

For struggling families, issues of basic survival can overtake concerns for education. Dueñas’ children are among the 65% of the district’s student population classified as economically disadvantaged.

Last fall, Dueñas pulled her family out of homelessness. From late 2017 until fall 2019, the family jumped around from friends’ garages to hotel rooms. Eventually, they stayed at a homeless shelter.

Today, Dueñas said, she’s focused on simply keeping her family in the two-bedroom apartment she managed to get with the help of a non-profit organization that has worked to get most of her rent subsidized. But she’s not sure how long that will last and what’s next for her as she waits for federally-subsidized Section 8 housing.

In the meantime, thanks to L.A. County’s pandemic moratorium on evictions, the family is not in immediate danger of becoming homeless. “I don’t want to fall into that thing again,” she said.

For months, Dueñas and her 18-year-old son, whose effort to get a GED at a local job corps was interrupted because of the coronavirus, have been searching for work as they get by on her welfare check and food stamps.

Dueñas said she has applied at grocery stores, retail shops and even for a position in the school district’s nutrition department. She attempted to apply online using one of her children’s laptops and the newly installed internet at home, but was unsure how to navigate websites.

Before the pandemic lockdowns, she tried to obtain her citizenship to access more resources and opportunities. But with programs sending her outside the city for prep classes, the locations were too far a commitment for a family without a car.

Recently, Dueñas has made efforts to connect with school administrators with hopes of at least obtaining hard copies of assignments for her children. She eventually managed to get homework for her 11-year-old grade schooler.

Even though Dueñas may not be able to provide direct help to her children, she said she knows the importance of a good education, and constantly stresses the point to them.

“I tell my children, they have a choice,” Dueñas said. “Education, wherever you go in the world, is very important. That will give you a better income. But I tell them, ‘don’t ever forget where you came from.”