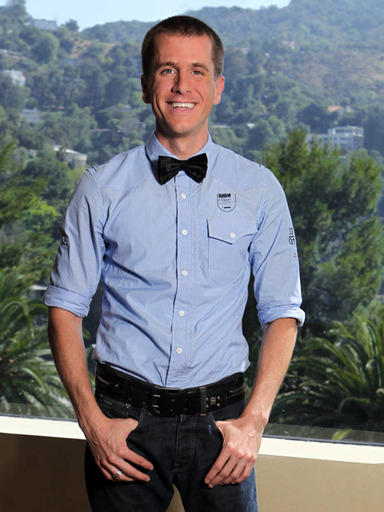

Ragan Fox—one of Cal State Long Beach’s most popular and recognized professors—has been recently selected as this year’s recipient of the Lilla A. Heston Award.

The award for “Outstanding Scholarship in Interpretation and Performance Studies” is given annually by the National Communication Association to researchers who have published significant works in the last three years.

Fox, now a resident of West Hollywood, never anticipated he’d be a teacher, much less winning awards for scholarship.

After obtaining his masters degree, he was optimistic about entering the workforce. Originally from Texas, he snatched his boyfriend, hit the road for San Francisco and faced a fierce truth: there were no jobs. Three months after the attacks of 9/11, Fox had to once again face Texas with, in his words, his tail between his legs.

While waiting tables and applying for doctoral programs, he was drawn into the arena of Communications, a wide-spread field of academic study that focuses on myriad ways in which humans communicate, from speech to non-verbal to broadcasting to performance.

“I decided on Communication because there weren’t many roles for gay guys in theatre,” Fox said. “I’d audition for roles in college plays and get called back for the ‘drunk, boisterous man in bar’ scene. So Performance Studies”—Fox’s emphasis within Communications—”focuses more on performance of marginalized literatures and personal narrative. I’ve always been drawn to gay texts and I love sharing stories about my trials and tribulations. My field has provided me unique opportunities to both produce and critique textual representations of gay life.”

The concept of performance is deeply ingrained in Fox since he uses it understand the intricacies of human interaction. His simple interpretation of Shakespeare’s line, “The world is but a stage,” for example, is to apply it to a server at a restaurant. Wearing a uniform and serving up regurgitated lines and smiles-for-pay, Fox points out that our identities are “theatrically rendered by way of clothing, lingo, storytelling and hairstyle. When most people define identity, they say, ‘Identity is who you are.’ But identity is what you do, what you enact.”

Fox was keenly aware of this concept when he appeared on CBS’s surveillance reality show Big Brother, where he even admits that his reading of critical literature still didn’t prepare him, at least entirely, for how hyperaware he had to be about his behaviors.

His straight counterparts on the show referred to him, as he pointed out, a “good representative of the gay community.” The caveat with such a back-handed compliment lies in that fact that, on a show branded for its manipulation of other human beings, it is dubious to claim one should be a “good representative” of any community.

“Viewer response taught me that people who have a problem with gays on TV don’t chalk up their hate to homophobia,” Fox said. “They all claim they have gay friends right after ripping into gay characters. Fan commentary also helped me understand the role that confirmation bias plays in interpreting gays on TV. Any misstep on my part, no matter how mundane, was used to substantiate anti-gay myths.”

In the end, it had little to do with who Fox is, but rather—to elaborate his point—what he did.

And when it comes to what he does for a living, do not inform Fox that his work—and those within the arts and humanities as a whole—lack a correlation to the real world. For him, these disciplines teach the basic skills needed to operate and function within an ever-altering world.

“What employer wants to hire a person who can’t expertly write, critically think and present ideas in an organized and persuasive manner?” he asks rhetorically. “Creative thought is the cornerstone of innovation and creative thinking takes practice.”

That creative thinking, where he engages students to not just read literature but to stage it, requires, at least for Fox, a sense of vision and risk. His students as well as his work help foster responsible, informed citizens as they engage in public policy debates and community service projects.

“[My students] make an investment in their community and in doing so, they are more active in the ‘real world’ than many who doubt the benefits of creative inquiry,” he says.

It is perhaps here, in his incessant persistence that students inquire about the world, that one finds the reason he is being recognized with the Lilla A. Heston Award.

Though he admits he is not sure if he is a fan of awards, he is happy to have the formal recognition since his name will reach a wider audience in a field where he said it is often harder to get the work read than do the actual research.

Of course, this recognition comes with a tinge of bittersweetness as he faces the possibility of a pay cut if Governor Brown’s tax initiative, Prop. 30, fails in November. But for him, it is essential for the continuation of what he is doing: not only creating and fostering inquisitive, creative citizens, but writing and researching the larger role of the LGBTQ community within history and communications.

“The situation is even more frustrating given that I [already] get paid less than scholars at research universities and have a higher cost of living,” he sadly states. “On the flip, I love what I do and have excellent benefits. I’m optimistic that the economy will turn around and educational funding will improve. The problem with saying funding can’t get worse is that, over the last ten years, the situation becomes more and more dire.”

Let’s perhaps, for a moment, sit on Fox’s side with his optimism—after all, what we do is more important than who we might think we are.