Photos courtesy of Nicole Miyahara and Kristine Carr.

One Saturday night, Nicole Miyahara stepped into Hamburger Mary’s for what was quickly becoming her tradition: to see a drag queen show.

However, chance had gotten the best of her tradition as, contrary to the theatrically decked out men-as-women she was used to seeing, she experienced the opposite: an array of women-as-men ready to delight and entertain her.

“I had never heard of drag kings before and I wanted to know why nobody knew about these performance artists,” Miyahara said.

Her feelings are not uncommon since, overwhelmingly, the drag scene is dominated by its queens. Tack on the exponentially-growing success of RuPaul’s Drag Race (which has yet to feature a single king) and drag kings begin to look like an overlooked subculture within a subculture within a subculture.

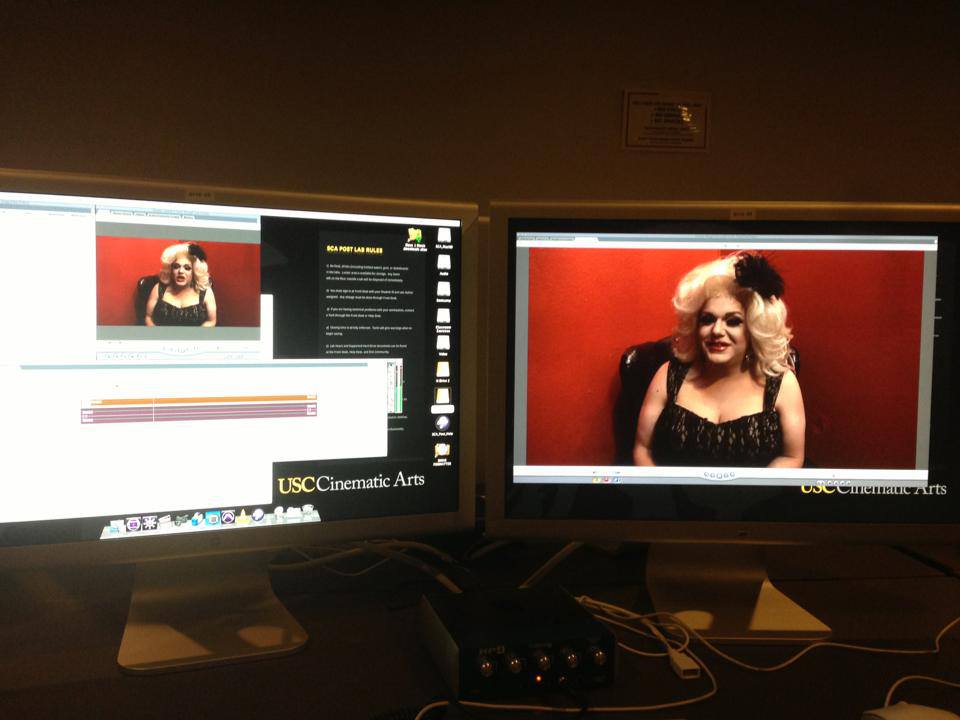

To share the talents of these kings, Miyahara—a graduate student of anthropology at the University of Southern California who actually switched her focus to drag king art before applying—has decided to document these dragsters in The Making of a King. Her main focus is on the Long Beach king himself, Landon Cider.

To share the talents of these kings, Miyahara—a graduate student of anthropology at the University of Southern California who actually switched her focus to drag king art before applying—has decided to document these dragsters in The Making of a King. Her main focus is on the Long Beach king himself, Landon Cider.

Those outside of drag culture most likely don’t know Landon (unless they caught him on Lady Gaga’s “Applause” lyric video dancing with the popstar while he was performing as Peter Pan). But those heavily involved know exactly who he is because—much like Jewels did here in Long Beach with her own ever-expanding brand—Landon is altering the drag king scene.

“I was a baby dyke going out to every gay bar in existence,” Landon (born Kristine Carr) said, “and I fell upon the [Jewels-created] Starlett Review at Hamburger Mary’s in Long Beach.”

Soon, Kristine’s summer became filled with the dramatic flair of drag performance as she saddled up as many times as she could to watch everyone from future RuPaul stars Morgan McMichaels and Raja to Jewels herself. This perpetual performance watching—paired her love of theatre and special effects make-up that she would tackle with utmost attention to detail every Halloween—turned her into an addict: While friends were more interested in drinking and chasing ladies, Kristine sat continually captivated by the Theatre of Drag.

“They weren’t just performing—they were storytelling with theatre and make-up and song,” Kristine said. “I fell in love with the drag but I didn’t think much of myself performing drag.”

That is, until she had to battle cancer for a year. As with all immense struggles—particularly those where life is put in the balance—the question of one’s existence becomes frighteningly clear.

“I was forced to look at my life and decide what I was going to do” she explained. “I made a checklist—one of them being that I had to get back on stage, no matter how.”

Traditional theatre, plagued by misogyny in the way women were cast—”I was always to play some type of princess needing to be saved by some prince”—was out of the question, Landon explains. And after much pondering, the energy and love she experienced at those many drag shows ultimately provided her the path to not only get back on stage, but to do it the way she wanted.

Landon Cider (left) and his creator, Kristine Carr (right).

Kristine’s discovery was that drag kings not only existed but existed as an entire community. However, she found that drag king culture—unlike the individuality, theatre, and humor often expressed in drag queen performance—was largely political and troupe-driven, much like NYC’s Switch N’Play. This was, in a certain sense, antithetical to what she wanted to do: entertain.

Her dedication to the Landon character she has created is taking her to drag stardom quite quickly, something that has been outside the norm thus far in most drag. After all, the arena is queen-dominated—but Landon is quick to avoid this oh-poor-me mentality about inequity in the drag scene, moreso even than he is quick to humbly point out how early in his career he actually is.

“I don’t know if I choose to be blind to it or have a naiveté about when it comes to feeling like I’m a second-class citizen within a niche because I’m a biological female,” Kristine said. “Other people point out that my struggles should be accepted and I should be accepted into larger competitions like RuPaul’s Drag Race. But to be honest, I don’t think it’s because I’m a female; I think it’s because I am not at the level yet they’re looking for.”

These points, idiosyncrasies, and nuances of Landon and his fellow kings are precisely what Nicole explores in her still-in-progress film.

“I made this for the heteronormative audience,” Nicole said. “I had been to hundreds of drag queen shows before and I held no negative perceptions of it. But so many don’t know, for one, that drag shows aren’t just for the queer community. They’re for everyone—including drag king shows. It’s just performance: give it a shot and once you see the film and see what these L.A. kings are capable of, I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it.”

“I made this for the heteronormative audience,” Nicole said. “I had been to hundreds of drag queen shows before and I held no negative perceptions of it. But so many don’t know, for one, that drag shows aren’t just for the queer community. They’re for everyone—including drag king shows. It’s just performance: give it a shot and once you see the film and see what these L.A. kings are capable of, I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it.”

An initial 30-minute version of the film will air for a private audience on September 8 at USC, but Nicole plans on continuing to shoot footage in order to make it a feature-length documentary, wherein she can continue to explore the diversity of talent that the drag king community holds.

“If they are familiar with stereotypes that surround drag kings,” Kristine said, “like a girl just putting on her dad’s clothes and acting like a butch lesbian on stage—that’s a stigma that drag kings have had forever. We’re breaking that. If they hold that thought, their minds can be changed by seeing us just once.”

For more information on The Making of a King, click here. For more information about Nicole Miyahara, click here. For more information about Landon Cider, click here.