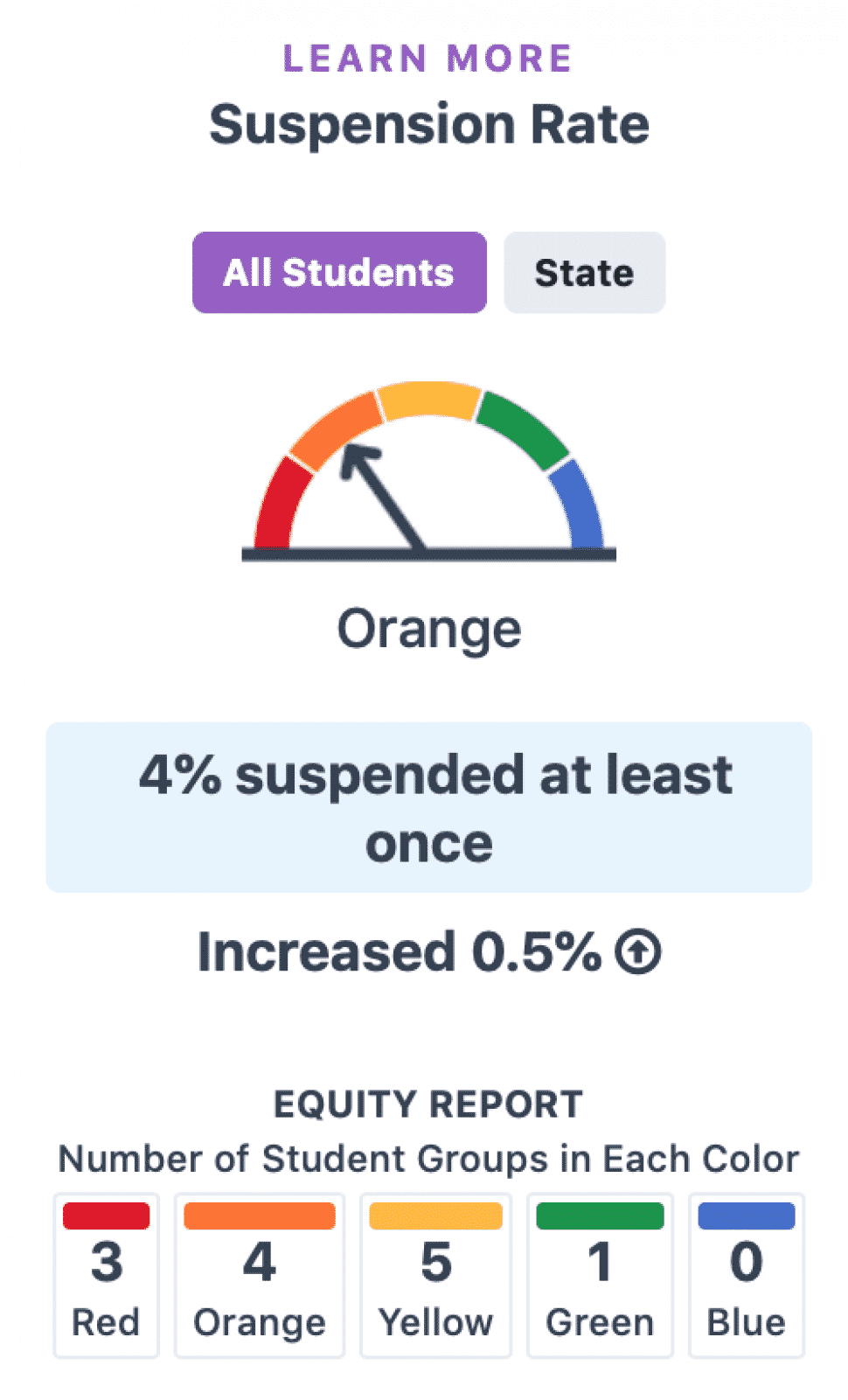

As California pushes to reduce the number of student suspensions, Long Beach Unified saw a slight uptick last year while overall state and county numbers dropped.

The school district suspended 4 percent of its students in 2017-18 school year, up from 3.5 percent the previous year. Statewide, 3.5 percent of students were suspended last year, down from 3.6 percent, while just 2 percent were suspended overall in Los Angeles County, according to statistics from the California Department of Education.

Though the district saw an increase last year, the numbers have dropped significantly in recent years as Long Beach Unified, like all of California, works to move away from suspension as a common punishment.

In 2013, for example, the district suspended 6.6 percent of students, while the suspension rate statewide was 5.2 percent. Overall, the number of out-of-school suspensions dropped 46 percent in California from 2011 through 2017.

Christopher Lund, an assistant superintendent for Long Beach Unified, said suspension, while still a necessary tool in some cases, has been historically overused in education. Lund pointed to some urban schools districts in the country where double digit suspension rates have done little to deter bad behavior.

“I think we’ve learned that if it’s not changing the behavior it’s not effective,” he said. “So in the last several years there’s really been a shift to keep kids in school, because it’s hard to learn if you’re not in school.”

As part of the shift, former President Barack Obama in 2014 issued a guidance encouraging states to reduce suspensions and improve disparities in student groups.

The state is also scrutinizing suspension rates as one of the measures of performance in the new, multicolored California School Dashboard.

Lund said one reason for the district’s slight increase last year was a shift in how the state measures suspensions. Last school year was the first year the state asked all districts to include partial day suspensions in their numbers, he said, adding that the overall numbers also include in-school suspension.

While higher than the state average, Long Beach’s rates are lower in comparison to similar urban districts, like Fresno Unified, which saw a 7.3 percent suspension rate last year, and Sacramento City Unified, which saw a 6.1 percent rate.

“Nationally, our suspension rates are very low,” Lund added.

Disparities persist

But while overall numbers drop, disparities persist.

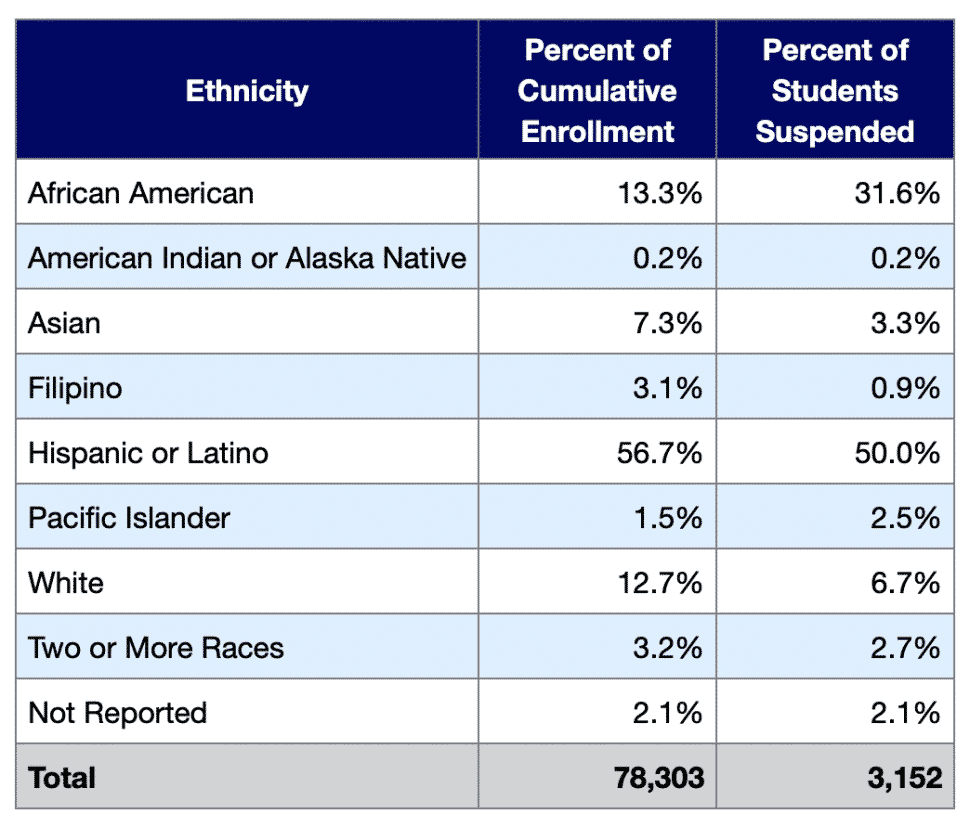

In Long Beach Unified, black students are suspended at significantly higher rates than other groups. Last year, black students represented 13 percent of students but accounted for 32 percent of suspensions.

In comparison, Latino students represented 57 percent of students and accounted for 50 percent of all suspensions.

The challenges are similar in the county and statewide. In Los Angeles County, black students represented 8 percent of the population but accounted for 29 percent of suspensions last year.

In Long Beach, the most common reasons for suspensions were violent incidents with no injuries and defiance.

Lund said the district is expecting lower numbers this year as it focuses on suspension rates for groups that have historically seen challenges, including black students, and special education, homeless and foster students.

But the district still has work to do, he said. “We’re paying close attention to the data.”

In another disparity, middle schools see much higher suspension rates than elementary and high schools, especially in the inner city.

Washington Middle School, located in a Downtown neighborhood with historically high crime and poverty rates, suspended nearly 11 percent of its students last school year—one of the highest rates in the district.

Principal Megan Traver said many of her students have trauma from living in a neighborhood where gangs, drugs and poverty are a daily reality.

“They can’t just pretend nothing has happened when they get to school,” she said. “They can’t just leave it at the door. That’s a lot to ask from someone who has been through a lot.”

Restorative justice

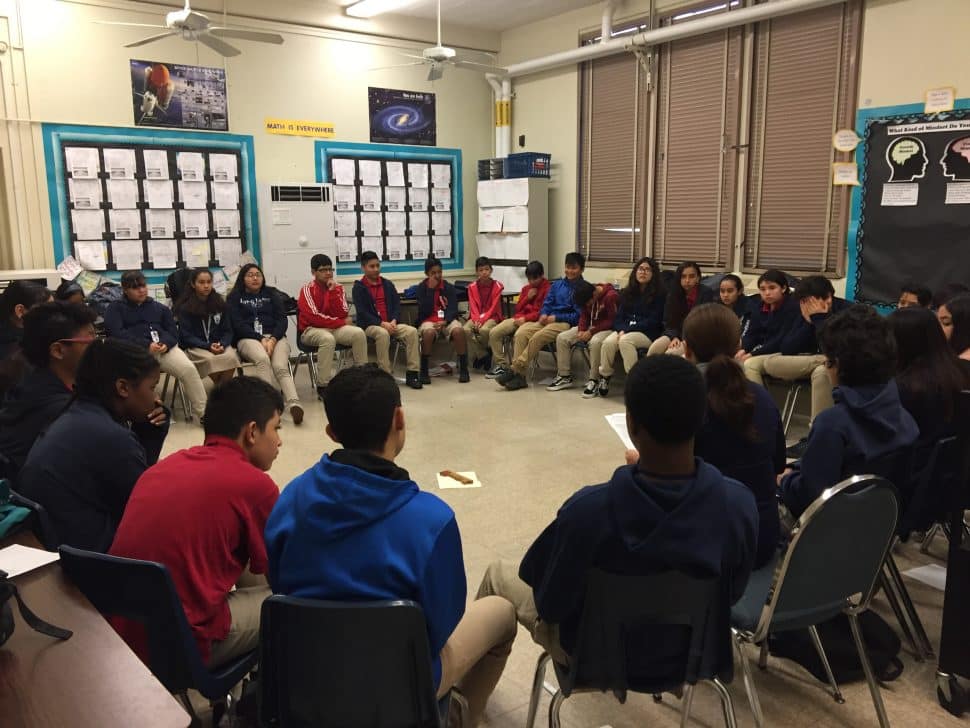

In an effort to lower suspension rates, some middle schools in Long Beach are using a practice called restorative justice, where typical punishment is replaced with mediation between the victim and the offender.

Traver said Washington began training its teachers in restorative justice about three years ago, and the school is now beginning to see the benefits. As part of the program, the school every three weeks holds community building circles in each classroom, where students talk about issues impacting their lives.

In a classroom on Wednesday, seventh-graders sat in a circle where they participated in an exercise focusing on their goals for the future.

“My goal is to be doctor,” said one girl.

“My goal is to get a job so I can help my mom,” said a boy.

Traver said the exercise helps students learn how to respect and support each other. By saying their goals out loud, they’re being held accountable for their future.

“We say to them, ‘OK you want to be a doctor, is that the way you would act if you want to become a doctor?'” she said.

With help from the restorative justice circles, Traver said, the climate has shifted in her school. Washington this year has seen a drop in serious offenses and so far has reduced its suspension rate by half, she said.

For the most serious offenses, like bringing a weapon to school, suspension is legally required, but in many cases, other forms of punishment can have better results, she added.

“We want students to have a sense of belonging,” she said. “We want them to understand that it’s not their fault, and in school they have support.”