A few dozen congregants—some in suits, some in jeans—sit on pews inside a cavernous Bluff Park sanctuary singing “Old Rugged Cross.”

On this Palm Sunday, the Rev. Dan Lewis of Grace United Methodist Church speaks about paradox. He recalls the story of Jesus riding a donkey into Jerusalem, tempting trouble from the Roman and Jewish authorities. His followers waved palm fronds, mimicking—perhaps mocking—the kind of triumphant welcome a warrior might have received.

One problem: “Jesus had no power,” Lewis says.

The start of Holy Week for Christians is dark and fraught with uncertainty. The hero of the story appears weak and passive; he is betrayed, deserted and killed.

LGBT clergy in the United Methodist Church find themselves in a similar paradox: Lewis preaches in a church a few blocks from where one of the largest Pride parades in the country marches each May. Yet because he is gay, his position in the worldwide denomination is fast becoming precarious.

Lewis, who came out while in seminary during the mid-1990s, is among hundreds of clergy in the roughly 13 million-member denomination standing at the crossroads of a years-long dispute over whether gay-friendly policies are compatible with Christian teaching.

For Lewis, the parallels to Holy Week are impossible to ignore: “We’re the ones poking the bear,” he says. “If we didn’t stand up, there would be no conflict at all.”

There is much at stake beyond whether the church remains united globally. For Lewis and at least one other gay pastor in Long Beach, the Rev. Mark Sturgess of Los Altos United Methodist in East Long Beach, it’s both deeply personal and practical.

If the progressive wing of the church breaks away as some predict, churches could lose their assets and property—some have already come close—while pastors’ financial security would be jeopardized.

“The only asset I have is my vocation,” said Sturgess, who worked in corporate America as a data analyst before he was ordained in 2002.

These matters likely won’t be sorted out for months or even years as the larger church, founded in England in the 18th century, struggles to find its way.

A significant development is expected this week, when the church’s judicial body meets in Evanston, Illinois, to determine whether a February vote by its legislative body was in line with the denominational “Book of Discipline.”

The General Conference in St. Louis a few months ago did not go the way progressives hoped: Delegates affirmed and strengthened language that the ordination of LGBT clergy and same-sex marriage would not be allowed.

This more conservative stance was led by a large delegation from Africa where the church is growing rapidly.

For Lewis, Sturgess, their congregations and many others who belong to the roughly half-dozen Methodist churches in Long Beach, this is indeed a dark time.

“I’m sad to lose something that I was born into and love,” Lewis said in a recent interview. “But I came to the conclusion that that which I knew is now dead.”

Taking sides

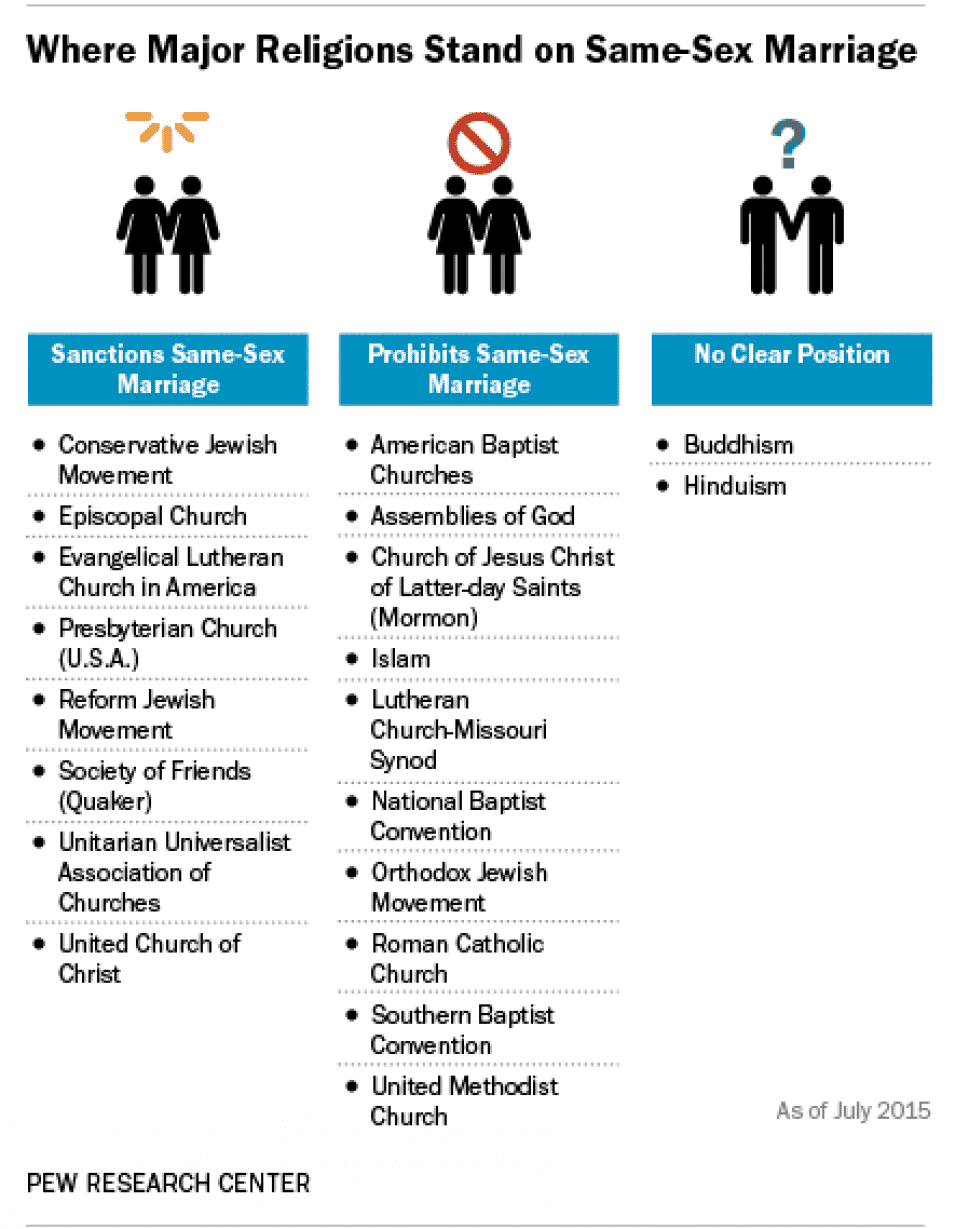

Other denominations have similarly struggled with debates over gay ordination and same-sex marriage.

The Presbyterian (U.S.A.), Evangelical Lutheran and Episcopal Church—the American branch of the Anglican Communion, or Church of England—have all embraced gay-friendly practices.

In these cases, it was the conservatives who left the denominational fold to form their own branches or align with more like-minded churches abroad.

A church in Long Beach, All Saints Anglican in Belmont Heights, was among the first in the country to shed its Episcopalian affiliation and align with conservative Anglican churches in Africa. The American Anglicans now have their own organizational structure—but that did not come without lengthy and expensive court battles over church buildings and property.

In 2002, a Methodist church in Fresno lost its property after breaking with the UMC over same-sex marriage but won it back after a court battle. Other feuds have occurred in San Francisco, Mississippi and West Virginia.

After years of weathering these localized battles, church progressives, who are concentrated in the Western Jurisdiction, were hopeful this year of a plan that would have allowed regional bodies to determine their own practices. The so-called One Church Plan, however, was rejected by a slim margin.

Since then momentum has swelled and opinions have calcified on both sides of the debate. Influential progressives and traditionalists have said in recent months that a schism is inevitable.

More than 1,000 congregations across the country have now signed on to become “reconciling” places where LGBT clergy and members are welcome.

And, in another development this week, some progressive congregations have requested that the money they send to the General Conference be diverted to other causes, such as a worldwide humanitarian fund, due to the “exclusion or judgment of LGBTQIA individuals.”

At the local level, members are still sorting through emotions. The Sunday after the General Conference vote, the Rev. Douglas Dickson of Cal Heights Methodist Church had members write down what they were feeling on sticky notes.

“It was pretty profound,” he said. “Pain, grief, anger—there was a sense of betrayal.”

The church has a number of LGBT members and staff. “I have no idea whether I’ll be a Methodist minister next year, but we intend to stand with them,” Dickson said.

‘Who else can we exclude’

The Methodist church in the United States has seen a 30% decline in membership over the last four decades—a trend similar to other Christian mainline denominations as younger people fall away from organized religion. UMC membership in the United States is 94% white, according to Pew Research; it is also aging, with 62% of members over 50.

“Our response?” wrote the Rev. William Willimon, a retired Methodist bishop, in an essay after the February gathering. “Spend millions of dollars and hours of work to decide who else we can exclude.”

Given Long Beach’s diversity, several local Methodist churches have worked hard to be more inclusive. Lewis’ church hosts a Samoan congregation, and offers a service in Khmer that is bustling with young kids. The church also collaborates with the Los Altos YMCA for community wellness and children’s programs.

Grace United has hosted the West Coast Chorale, a Yoga Church, Art Smart Studio for Kids, Patrick Henry Elementary School family dance and the Filipino Migrant Center. It is considering the addition of a Spanish language service and an LGBTQIA ministry.

The vast circular building at Third Street and Junipero Avenue, he concedes, is still underutilized and difficult to maintain.

The much-publicized divisions in the denomination—the February vote made national headlines—have not helped.

“This has created a PR nightmare,” Lewis said.

The way forward

Lewis, 50, is the son of a Methodist minister from Montana. He doesn’t remember being taught anything anti-gay in his youth, yet he knew Montana was not a safe place to explore his sexuality.

He went to seminary in 1995 in Denver, where he was surrounded by classmates who were out and “healthy, productive, respected, educated, employed—all of the things that didn’t match what I believed being gay was,” Lewis said.

Both he and Sturgess described seminary as a deconstructive environment, both theologically and personally; it’s a place where ideas about everything are challenged.

“I got to examine who I thought I was and who I was,” Lewis said. “That was the end of my uncertainty, and years and years of depression.”

Sturgess was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 2002. He came to the Methodist church in 2014, a few years after coming out as gay in a letter during Holy Week in which he described the anxiety, self-loathing and “toxic perfectionism” he had suffered.

Coming out wasn’t so much an act of courage, he says: “It was the only path to living authentically.”

Both Lewis and Sturgess have long served in areas of Southern California that are generally affirming of LGBT people. They feel fortunate, but know that they will be called to be among the leaders in this movement.

“My heart really goes out to other people in the country; they’re not safe from their depression,” Lewis said. “I have a huge safety net—I feel privileged—but I don’t want to rest.”

Neither pastor knows or is willing to predict what may come of the denomination. Even if the Judicial Council strikes down parts of the February decision, observers say another vote is inevitable—and the larger church is growing fastest in places that are more conservative.

Local leaders do, however, take solace in knowing the miraculous and unexpected end of the Holy Week story.

“Easter arrives,” Lewis said, “and hope is restored.”