Photos by Jason Ruiz.

Nearly seventy students pack into the stuffy third-floor classroom of a Fine Arts building at California State University Long Beach. It’s Friday evening, and while most people are sitting in rush hour traffic in the parking lot that is the 405, these students are anxiously counting down the minutes until the clock strikes five.

At that time a gauntlet will be thrown down.

Aubry Mintz, the head of the animation program at CSULB, will announce the premise of this year’s 24-Hour Animation Contest, and nearly 250 students across the nation (and for the first time this year, internationally) will work through the night to conceptualize and complete an animated film in a nearly impossible amount of time.

“To do this in 24 hours is stupid,” Mintz said, laughing. “It’s ridiculous.”

The contest started nearly a decade ago when Mintz, who had just moved to California permanently, wanted to push his students at Laguna College to do more. He wanted them to work as hard as him, so he laid out the proposal to stay overnight and create until they couldn’t create anymore. Five brave souls took Mintz up on his challenge and the 24-hour contest was born.

“I started this contest about 10 years ago because my students weren’t working hard enough,” Mintz said. “I challenged them to stay as late as me and we ended up watching the sun rise together. They worked harder than they had the entire semester.”

The simplicity of the premise downplays the daunting task that follows the start of the contest. At 5PM, Mintz announces the premise and the students have 24 hours to create, design and complete a 30-second animated film. Mintz admits that in the professional world, 30 seconds of animation typically takes 3 to 5 months to complete.

The theme for this year is A quote from George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a favorite of Mintz’s. He explained that it just hit him as he woke the morning of the competition. He used the same quote in an art project he completed in middle school.

“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

The only stipulations are that each frame of art must be manipulated, there can be no faculty help and then, of course, the small detail about needing to finish in 24 hours. As he announces the theme, some students groan while others wonder aloud what an animal farm is. No matter, it’s 5PM. It’s time to freak out.

The students break into their teams of five. True to tonight’s theme, some teams are more equal than others, because some teams have more experience than others. Mintz opens the competition to beginning students, and some of the ones who were brave enough to toss their hat into the ring with the upper classmen are the most wide-eyed. Kim Dwinell, a professor who teaches beginning animation at CSULB points out some of her students who look like deer in front of an animated MAC truck. But, she conceded, they will overcome it and the experience will be great for them.

The students break into their teams of five. True to tonight’s theme, some teams are more equal than others, because some teams have more experience than others. Mintz opens the competition to beginning students, and some of the ones who were brave enough to toss their hat into the ring with the upper classmen are the most wide-eyed. Kim Dwinell, a professor who teaches beginning animation at CSULB points out some of her students who look like deer in front of an animated MAC truck. But, she conceded, they will overcome it and the experience will be great for them.

“I’ve worked in animation before,” Dwinell said. “This is very much like finishing a film where people are sleeping on their cubicle floors and there’s that energy and you’re exhausted but then you see what you’ve done last week and you’re excited. It’s up and down.”

This is her second 24-hour contest. Last year she stayed well into the night, strumming a ukelele, trying to quell the anxiety and frantic nature of the contest with the rhythmic plucking of some soothing chords. She said that with all the junk food and caffeine, there’s the inevitable crash that will hit in the hours before the sunrise, but come morning the resilience of the students will carry them through toward completion.

“When you come visit them in the morning they’re disheveled and they’re napping in corners and it looks like a homeless encampment,” Dwinell said. “But they’re drawing like crazy and then the energy starts to pick back up.”

There is a live feed connecting campuses from California, Tennessee and Michigan across the globe to classrooms in Australia and to Sheridan College in Toronto, Mintz’s alma mater. There is a confessional in the back room of the CSULB headquarters where students will go and share their emotional rants, fueled by coffee and sleep deprivation. And there is enough taurine and guarana to kill a herd of small horses.

Some might say he’s casting the students off on a voyage toward disappointment because of the sheer impossibility of the task, but he does it to challenge them. He’s trying to build something at CSULB and it will take stepping out of comfort zones and finding new limits to their abilities.

“Starting a culture at any school is hard,” Mintz said. “And what I mean by that is that you get students that want to be here and they’re not just getting assignments and doing homework. The find the meaning in it, they see the bigger picture. To me, this contest helps create a culture where it’s a meaningful experience to them and they create projects knowing that its outside themselves.”

That culture-building that Mintz has helped spur along as head of the animation department has others taking notice. In May, Animation Career Review ranked CSULB as the No. 7 animation program on the West Coast and No. 22 nationally. The rankings considered hundreds of schools across the country and based their ratings on academic reputation, admission selectivity, economic value and the depth and breadth of the faculty and the program.

The faculty in the department say that Mintz is the driver of the program and always wants to push further and harder. However, he is cautious not to lean on the students too much. From his personal educational experiences in his native Canada, he knows that pushing too hard can cause students to burn out or lose their passion.

“I don’t want that to happen,” Mintz said. “I want this place where its still enjoyable yet they’re taking risks, pushing their boundaries and finding out something new about themselves.”

“I don’t want that to happen,” Mintz said. “I want this place where its still enjoyable yet they’re taking risks, pushing their boundaries and finding out something new about themselves.”

So the students work through the night, fighting back the urge to sleep and the bigger urge to cast off constructive criticism. Mintz says a major lesson taken away from this competition is the collaborative element. Very few people posses all the tools to produce an animated film on their own, so making the students work as a unit is beneficial in the long run.

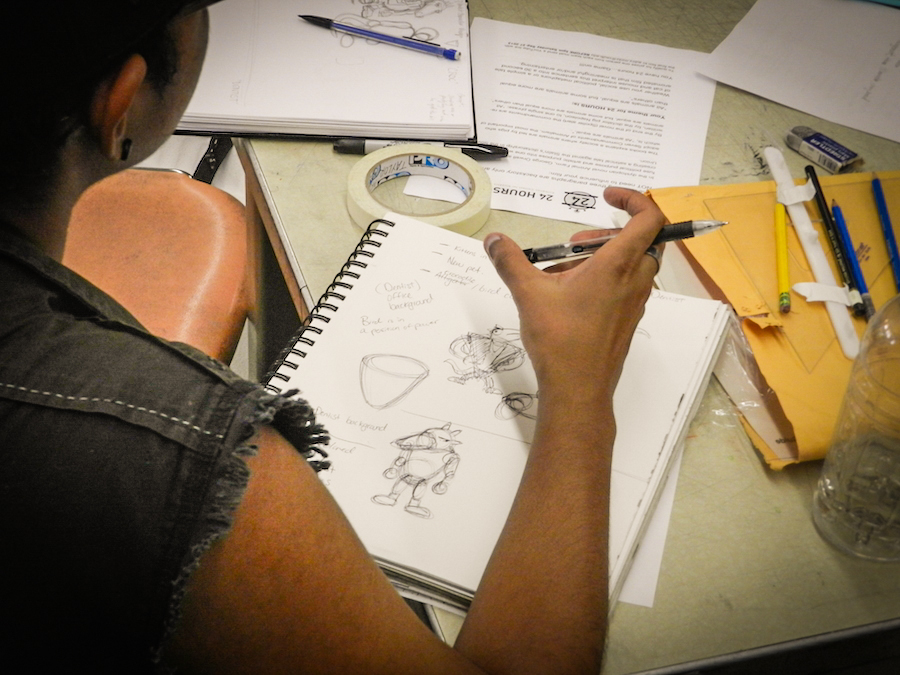

Ideas become storyboards as night becomes day. Some team members seek refuge across the hall in the only air-conditioned class room, but they were informed any sleep they thought they might get will be cut short by the entrance of a debate team in the morning. Others just set up camp wherever they can lay their bodies. This is college; sleeping on lawns, hallways and the library is normal, so nobody bats an eye.

The aftermath of clipping, splicing and storyboarding was reminiscent of an all-night frat party minus the Jäger bombs. Red Solo cups and Del Taco wrappers were strewn across the ground and desktops served as graveyards for empty energy drink cans. Despite the caffeine levels there was an air of calm as the clocked counted down the final hour of the competition.

“I think right now we’re too tired to be frantic,” said 19-year-old Elianne Melendez, a competitor and president of the Society of Student Illustrators and Animators on campus. “We reached that point at 3am. A lot of people were going outside and taking laps.”

Melendez had another reason to be calm: her team was finished. The group, named Animators Anonymous, used cut-out animation to tell the story of two ducks vying for one spot on a shelf at a toy store. Everyone on her team is a beginner, and their lack of experience forces them to think outside the box and compose their project through an avenue that is used less frequently these days, given technological advances in the field.

They shot their entire 30-second film in the hallway, meticulously moving cut-outs of ducks, hands and people to compile the over-700 frames needed to meet the time mark. Melendez’s group was able to outline and decide on a premise quickly, helping them to finish with time still left on the clock and sparing them from the desperate search for inspiration that other contestants faced.

She recounted walking out to the parking lot early in the morning and noticing a classmate laying spread-eagle on the pavement, staring up at the sky. He bolted up when Melendez walked by and they shared a moment of awkward silence before both just chalked it up to the 24-hour contest digging its hooks into their psyches.

She recounted walking out to the parking lot early in the morning and noticing a classmate laying spread-eagle on the pavement, staring up at the sky. He bolted up when Melendez walked by and they shared a moment of awkward silence before both just chalked it up to the 24-hour contest digging its hooks into their psyches.

“I walked by and they kind of just quickly sat up and we just looked at each other, didn’t say anything and kind of just looked away and accepted that this was just part of the experience,” Melendez said.

Shawn Serdinha, a first-year animation student and member of team 200 Percent Animation—they say they give twice as much effort as their competitors—said for students in his position, being around more advanced animators is beneficial. Even though it was a competition, he described the atmosphere as familial instead of fractious. Besides, win, lose or draw, the contest is a contest. Everyone here is interested in post-graduation employment and just being part of the contest is a great addition to the resumé.

“I think being able to show our talents as a team when we’re put under stress,” Serdinha said. “I think that being able to show with the amount of stress put upon us and lack of sleep that we’re still able to perform well is a great to show on a portfolio.”