The attempted impregnation of Gatsby, an 8-year-old zebra shark at the Aquarium of the Pacific, was anything but romantic.

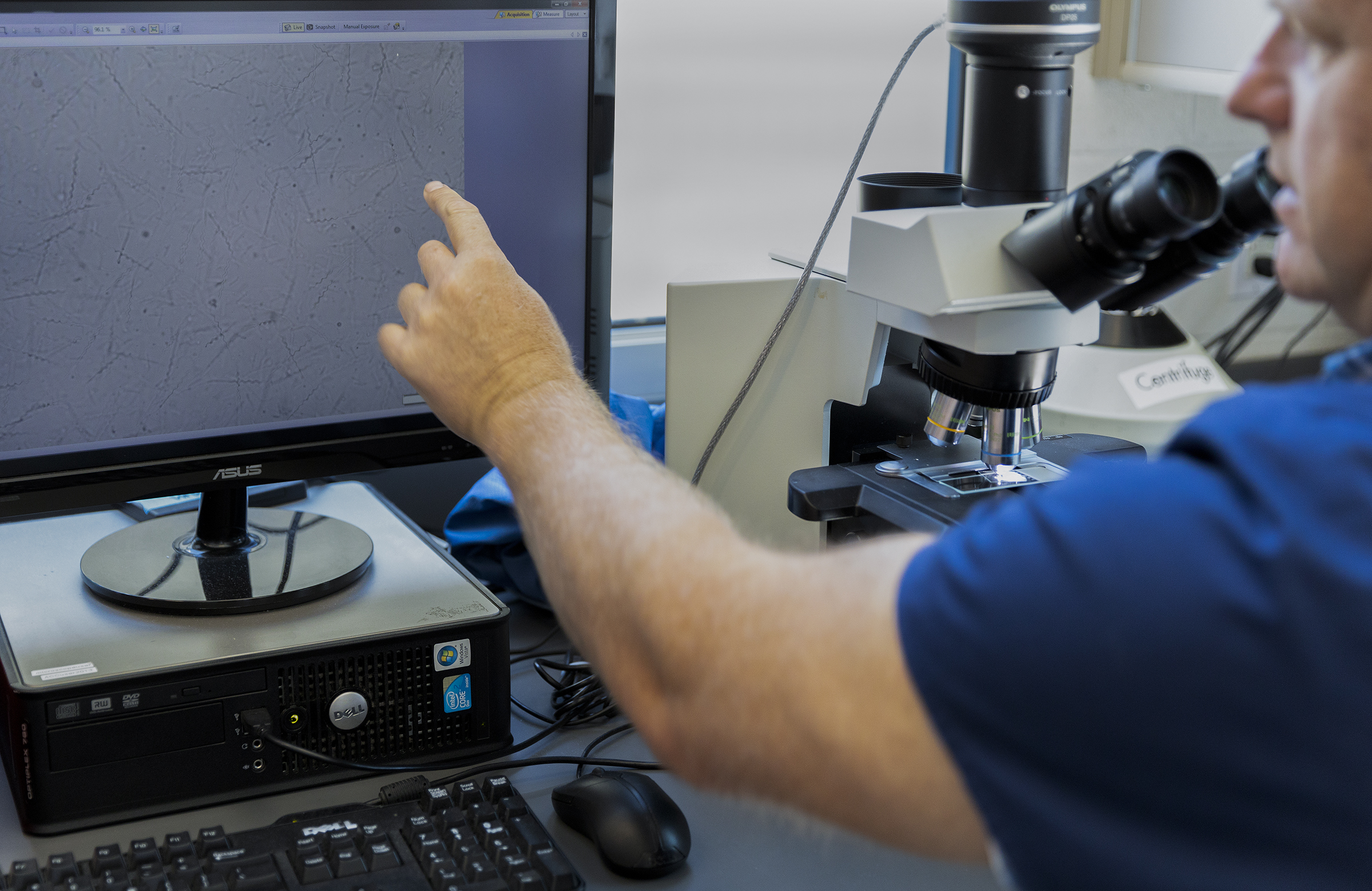

This week, after receiving a package of semen through UPS from a male shark in South Carolina, divers at the aquarium plunged into a 350,000-gallon tank, turned Gatsby upside down, held her still and used a catheter to inject the specimen.

Staffers artificially inseminated the 130-pound shark as a part of a larger effort to help grow the population of species like Gatsby’s. Zebra sharks are currently listed as “vulnerable,” meaning their numbers are decreasing.

Gatsby’s artificial insemination marks the second in the aquarium’s history on a zebra shark, the first being in 2013 with Gatsby’s mother, Fern.

If Gatsby is pregnant within the next 10 days of insemination, she could lay three to six eggs.

While zebra sharks can mate just fine on their own without human intervention, the aquarium prefers artificial insemination to reduce physical harm to the female zebra shark and minimize the resources used.

During natural mating rituals, a male zebra shark, which is a bit smaller than the female, can be a little too rough with his lover. They are “aggressive breeders,” said Lance Adams, the veterinarian who cares for the aquarium’s 12,000 animals.

The male zebra shark will repeatedly bite the female, pin her down and then fertilize her. While this mating practice is normal, it wounds and cosmetically scars the female shark, Adams said. In the aquarium’s public setting, attendees who admire a wounded shark swimming in a tank might not fully understand why she’s injured. So, reducing physical harm to the female shark also helps with any misconceptions of abuse.

Artificial insemination also maximizes resources. Transporting a zebra shark to another facility takes more people power and time and requires monitoring of the shark’s well-being during transport.

Overall, artificial insemination is a form of “sustainable animal management,” meaning, humans can have control of the baby-making environment for the sea life.

“There’s still a lot of things to work out,” Adams said.

Adams credits the zebra shark’s declining numbers to fishermen targeting them for fin soup. Once captured, they’ll cut off their fins and through their remains back into the water, Adams says. The meat is also sold fresh and salt-dried and is used in fishmeal, making humans the biggest threat to the species’ endangerment, conservationists say.

Zebra sharks typically grow to be about 8 feet long and can live for nearly 30 years. They are found in the tropical western Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea near coral and rocky reef habitats.

The aquarium has made breakthroughs with other species, such as artificially inseminating giants seabass and white abalone, a plant-eating marine snail, and hatching their first giant seabass egg, Claire Atkinson, an aquarium spokesperson, said.

The beauty of collaborating with wildlife agencies or other aquariums, Atkinson added, is that each entity can build off of the other’s research and breakthroughs. Government agencies, for instance, yield a wealth of research, but they don’t know how to breed fish like the aquariums do, Atkinson said.

Aquatic facilities can one-up each other on their breakthroughs, too. A facility in Fullerton, Atkinson said, was able to breed hundreds more seabass than Long Beach, based on the aquarium’s research.

“It seems like no one facility can do this by themselves,” Atkinson said.

Conservationists like Adams continue to test the waters with endangered species. Before, he had used a same-day sample. For the recent insemination, Adams was able to use a day-old semen sample, continuing to push the boundaries of knowledge related to a specimen’s shelf life. The day’s lesson could help help shark conservation in the future, he says.

“We want there to be sharks forever.”