Almost four years after a man’s body was unearthed in his yard, 55-year-old Scott Leo sat before a jury Wednesday while lawyers began crafting competing pictures of him as a drug-peddling predator and an upstanding citizen who only occasionally hosted narcotics-fueled sex parties.

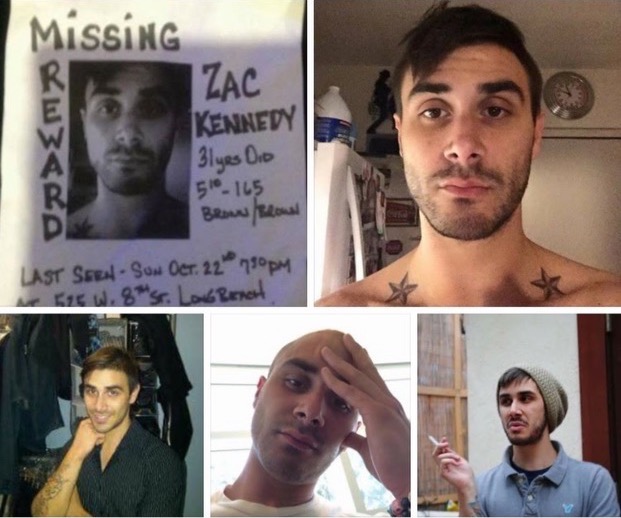

Leo has become the central figure in the death of 31-year-old Zach Kennedy, who disappeared on Oct. 22, 2017, about a decade after he moved to Long Beach from his small-town home in Pennsylvania.

Kennedy was one of the men who attended parties at Leo’s Downtown home, where witnesses say meth and the sedative GHB were freely passed around.

That night, Kennedy passed out from a likely overdose, and, fearing attention from police, Leo let Kennedy die in his bathtub instead of calling for help, authorities allege.

In the years of hearings leading up to this week’s trial, Leo’s attorney, Matthew Kaestner, has essentially admitted this, but he’s successfully argued it was not homicide, pointing out that Leo did not have the same duty to care for his guest as a parent would for a child or a doctor would for a patient.

Judges have repeatedly thrown out murder and manslaughter charges against Leo, so the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office is left prosecuting him for allegedly furnishing meth, furnishing GHB and maintaining his home as a place to use drugs.

“This is a place where he has used it and made it so he can continuously invite people over to engage in the use of illegal narcotics,” Deputy District Attorney Simone Shay told jurors in her opening statement Wednesday morning.

The charges against Leo could net him about six years in prison as opposed to the 15-to-life sentence a murder conviction would have. He’s currently free on $100,000 bail.

As she introduced her case, Shay said she plans to present text messages and communications from dating apps to show Leo used drugs, which he called “party faves,” to repeatedly lure men to his home. In her opening pitch to jurors, she sought to separate the illegal drug use from the sexual activity.

“We are not here to pass judgment on the lifestyle,” she said—but explained that the private, sometimes explicit, communications will shed light on his priorities.

For instance, when Kennedy appeared to be overdosing on GHB on Oct. 22, 2017, Leo texted a friend asking for help moving him, saying the last thing he needed was another visit from the police, who’d lectured him and other party guests about drug use about two weeks earlier when someone falsely reported a crime at his home, prompting officers to arrive and pull Leo, naked, out of the basement.

This time, police did not arrive. Detectives say Leo instead sent his friend a picture of Kennedy slumped forward in the tub, face pressed against the porcelain, his eyes partially open.

When Shay put the photo on an overhead projector, Kennedy’s father, watching from the audience, turned his head away; when the photo lingered, he walked out—momentarily escaping the courtroom where his son’s drug use and sexual history have been parsed out in excruciating detail.

Defense attorney Kaestner highlighted Kennedy’s drug use again and again as he began making his case to jurors. He called Kennedy a daily meth user, shooting up so frequently he could no longer find veins in his arms—a description the prosecutor repeatedly objected to and the judge ruled out of bounds.

By contrast, Kaestner said, Leo had a steady job in client development at a white-shoe law firm. He owned his well-kept house in Long Beach not to do drugs but because, “It was his home, where he lived.”

At the time of Kennedy’s death, Leo “had a well-respected position,” but, “As a gay man, he liked to have sex with other gay men, and from time to time do drugs,” Kaestner said.

Isn’t it more likely, he asked, that Kennedy supplied the drugs he used at Leo’s?

“What the government is trying to do,” Kaestner said, “is find that person to blame, to point that finger of blame in a tragic overdose death.” In this case, Kaestner admitted, it’s tempting to pick Leo for that role.

After Kennedy died and his friends came looking for him, Leo lied, saying Kennedy had walked away from his home. But after a months-long search, detectives unearthed his body in Leo’s backyard. It had been wrapped in a shower curtain and bag before being buried in a plastic tub. Presumably, to fit the body into the container, Kennedy’s feet had been severed at his ankles and wrapped separately.

Kaestner urged the jury not to let the horror of that discovery cloud their judgment. He accused prosecutors of being “long on the talk about Zach overdosing and being buried in Leo’s yard and very short on evidence that Mr. Leo gave Zach the drugs that caused his death.”

But Leo’s callousness in response to Kennedy’s death may be an integral part of the prosecution’s case. Even after hiding a body in his yard, Shay told jurors, Leo was more interested in continuing his drug use than learning from the overdose.

In February 2018, as Kennedy’s body lay underground, Leo was messaging another man, offering him meth and GHB if he’d come over for a party.

“What we see,” she said, “is this defendant has a plan for his home.”

For years, a father pressed for justice; now the lurid details of his son’s death are a trial issue