The man in the photo looked like her father, but Sounmi Campbell needed to be sure.

Phillip Campbell had disappeared almost 20 years earlier in a fog of mental illness that abruptly drove him from his sister’s home in Georgia. A trail of letters, the final ones postmarked from Long Beach more than a decade ago, was his family’s last clue to his whereabouts.

The letters eventually stopped, but the search didn’t. From the East Coast, Sounmi’s sister-in-law was scouring online records. In 2017, as she Googled the name Phillip Campbell, she saw it associated for the first time with Misi Tagaloa, a prominent pastor in Long Beach who has run for City Council three times.

What were the chances this could be their Phillip Campbell?

For months, Sounmi said, her sister-in-law tried to reach the pastor, but he would take weeks to respond. When he eventually provided a photo of a man he knew as Phillip Campbell, Sounmi was stunned.

“When the picture came up, I was like, oh my god,” she said. In the man’s face—with an unmistakable hawk nose the entire family seems to share—she saw herself. They arranged a phone call.

Tell me, Sounmi asked this Phillip Campbell, the names of your children.

The man strained to speak, but when he said the word “Sounmi” she knew: “That’s Daddy,” she said. “So, we rushed to him.”

For years, Sounmi had feared her father was dead or living on the street, so she at first was grateful Campbell was under the care of Tagaloa, who leads the Second Samoan Congregational Church on the outskirts of Downtown Long Beach.

Campbell was living in a home next to the church’s sanctuary. Inside, the conditions weren’t ideal, according to his family, who said he was sleeping on a couch in the house with several other homeless men. But at least he was safe.

That gratitude has since soured as investigators from the Long Beach Police Department and state Department of Justice unwound Tagaloa’s financial relationship with Campbell.

“This is clearly abuse of my father,” Sounmi said after seeing the breadth of the accusations laid out in a 14-page affidavit filed by state prosecutors earlier this year and obtained by the Long Beach Post last week.

Tagaloa’s crime, the document alleges, spanned years, with the pastor gaining power of attorney over Campbell, a schizophrenic man in his 60s who had lost the ability to properly care for himself.

While managing Campbell’s finances, prosecutors say, Tagaloa embezzled more than $100,000.

The California Attorney General’s Office charged Tagaloa in August with felony counts of grand theft and theft from an elder dependent, but the case has remained largely out of public view with Tagaloa free on $70,000 bail as he progresses slowly toward trial.

Tagaloa has pleaded not guilty and remains the public face of the Second Samoan Church. It’s unclear if his congregation knows about the criminal charges. Board members at the church did not respond to messages.

Tagaloa’s attorney also did not respond, and the pastor declined to comment.

“I have nothing to say at this time,” he said in an email.

Sounmi is now considering suing Tagaloa. She’s come to believe he was trying to hide her father to continue stealing his $2,900 monthly VA benefits. If the pastor had been more forthcoming, perhaps, she thinks, they could have gotten Campbell help before his condition declined even more.

“The fact that my father is a retired, honorably discharged veteran, suffering from mental issues—you hear that story all the time—but then we add this additional, just disgusting behavior from someone who is trusted in the community,” Sounmi said, “it’s just sad.”

A life derailed

As a younger man, Campbell was brilliant with numbers and fiercely self-sufficient, according to Sounmi. At the time, he was friendly and outgoing to the point of embarrassment for his daughter “because he would talk to everyone, but that’s just who he was.”

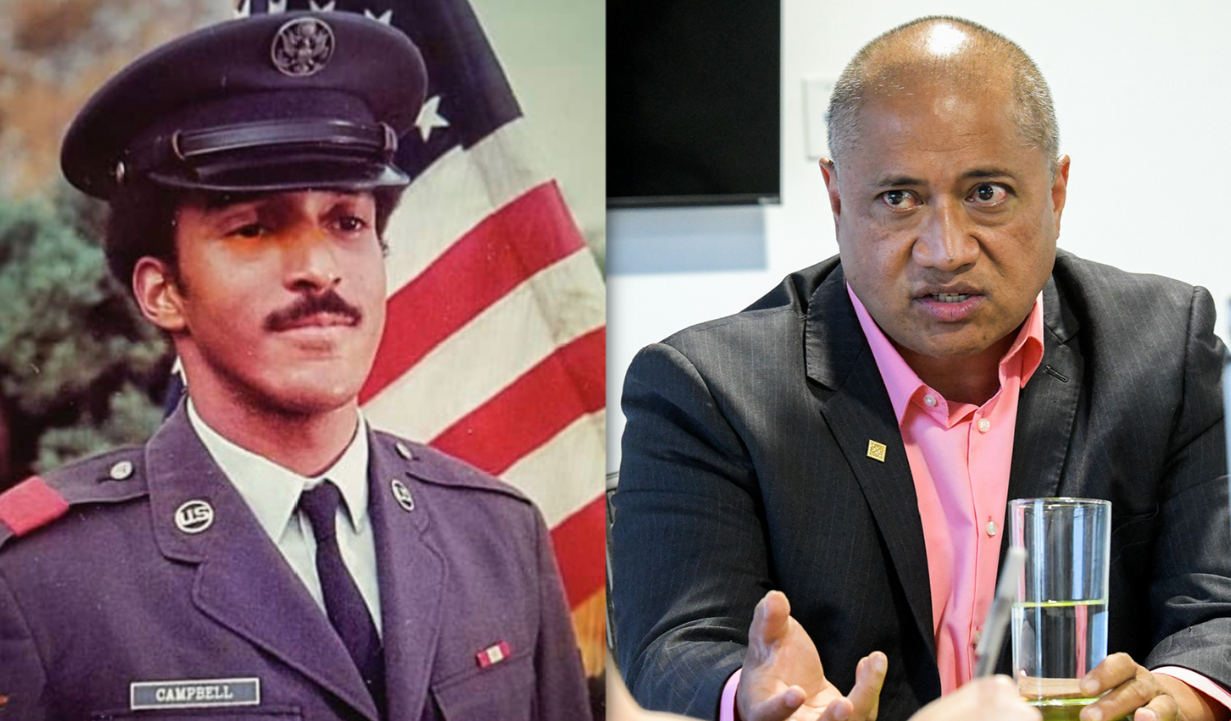

A black belt in Taekwondo who joined the Air Force at 17, Campbell was always physically fit, but his mental health became a continuous struggle.

After 13 years in the military, Campbell left with an honorable discharge when he started showing signs of schizophrenia, his sister Madena Stevens said.

In his 30s at that point, Campbell moved in with his mother in North Carolina where she managed his treatment. He was restless, according to his family, refusing to go on disability and insisting he was fine once the medication kicked in.

“So, pride of a man, especially back then in those days,” his niece, Patrice Stevens, said.

That restlessness only grew over the next decade as Campbell and his mother joined Madena and Patrice in New York City.

By then, Campbell’s mother was battling dementia and started forgetting her son’s medication, according to Patrice.

When the family realized this, she said, “He was way off of them, and it was hard to kind of get him back on because she, pretty much, she took care of him.”

Campbell took off for Georgia to live with a different sister, who struggled to make him see a doctor or even bathe.

One day, Madena said, “she came home and he was gone, and his stuff was gone.”

It’s not clear how Campbell crossed paths with Tagaloa years later. His family suspects they came into contact through Second Samoan’s homeless outreach, and Campbell, ever the talkative one, introduced himself.

Compassion for the homeless has long been a cornerstone of Tagaloa’s ministry, and he’s campaigned for City Council on a platform of building more affordable housing.

“If you have a pulse, if you can breathe, you’re semi-coherent, you deserve a place to sleep,” Tagaloa told the local news site Forthe.org. Love, he said, should be the guiding principle in how people are treated: “We just need to do it in so many different ways at several layers so that people come to their senses and then they love themselves. And then after they love themselves, they love their neighbor. And then maybe they’ll learn to love God.”

The nexus of his ministry and politics drew scrutiny in 2009 when Tagaloa’s campaign focused on registering homeless residents to vote. Eighty of them used his church as their address, raising questions about whether they actually lived in the council district where they’d be casting a ballot, the Press-Telegram reported at the time.

Tagaloa told the newspaper that about 30 homeless people used Second Samoan as their mailing address, “which may have caused confusion that led to the other 50 being registered with that address as well,” the Press-Telegram wrote in an editorial.

Others speak glowingly of Tagaloa’s ministry. A formerly homeless man told Forthe.org that he credits the pastor with turning his life around and helping him get a job as a truck driver.

In his most recent run for City Council, Tagaloa suggested “legislating compassion.” The volunteer-run food distributions at his church only go so far, he said during a candidates debate.

“Here’s the dead secret about homelessness,” he said. With food stamps, cash relief and emergency benefits they’re entitled to, “every homeless out there is walking around with a $1,000 check a month.”

If the community simply found a way to house 2,000 of those individuals, they could tap into their pooled aid money and “leverage $2 million a month to help solve the homelessness crisis.”

Madena estimates her brother had been living out of Tagaloa’s church since some time before 2013. By 2016, Tagaloa was applying to manage Campbell’s VA benefits, according to investigators’ account in their 14-page affidavit. As part of the application, the pastor signed an agreement pledging to use the money only for Campbell’s benefit.

As soon as 2017, the VA flagged a questionable expense. In August that year, officials asked Tagaloa to justify a $4,390 payment to ClickSound & Stage, the name of a Norwalk-based stage and sound equipment rental company.

When investigators circled back for a closer look, they found a host of suspicious payments starting as early as 2016, according to the affidavit. They allege Campbell’s account was charged $356 at Men’s Suit Outlet, $913.11 to TNT Electric Signs, $318 to A & A Towing, $1,000 for rent at “Second Samoan,” followed three days later by another $1,200 to the church.

There was a flurry of spending from Campbell’s account on one day in February 2017, the affidavit says: a total of $2,477.75 at what appear to be clothing and apparel stores like Judy Blue Jeans USA, LAJEWELRYPLAZADOTCOM and Capella Apparel Co.

More charges would follow, according to the affidavit: hundreds of dollars to restaurants and donations to local community groups along with thousands directly to Tagaloa’s church.

After their initial contact, Campbell’s family said they remained largely in the dark about how his money was being spent. Instead, they were soon plunged into a new search.

Reunion cut short

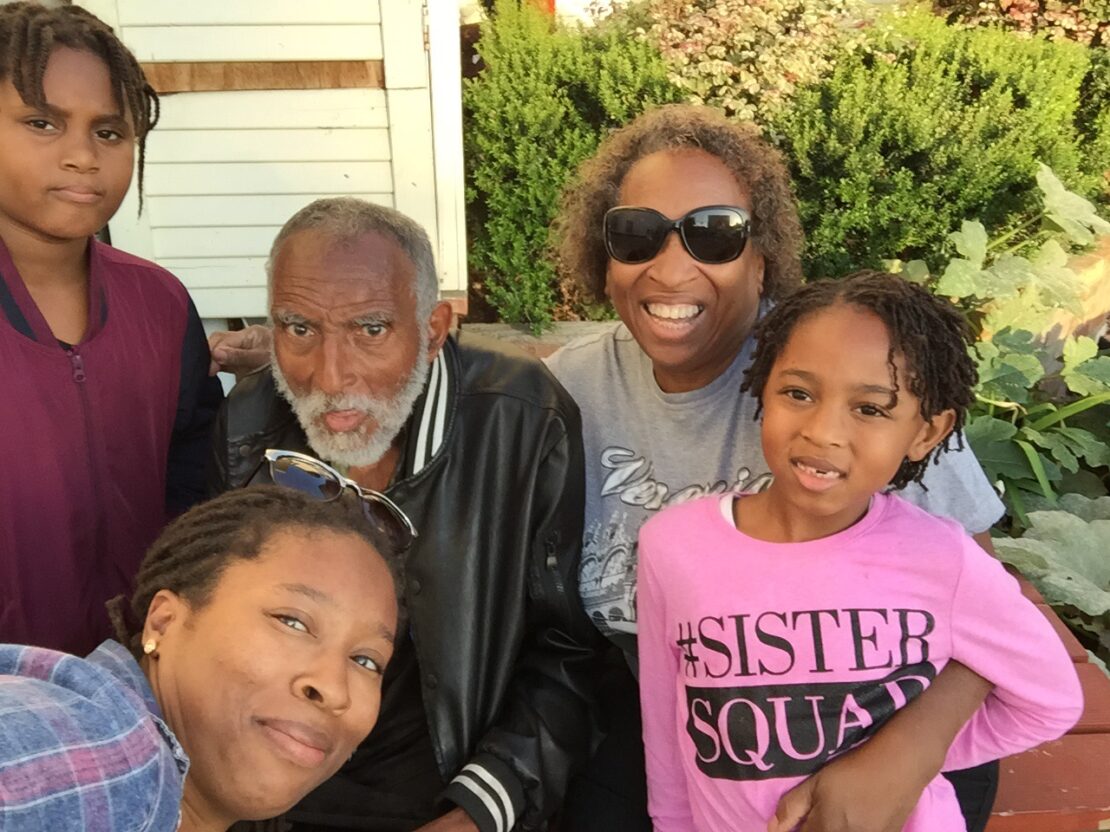

After Sounmi heard her father’s voice in 2017, the family moved quickly to reunite with him.

Managing their careers and families on the East Coast, Sounmi and her brother tapped Campbell’s sister Madena, who lives in Arizona, to visit in person. Almost immediately, she was on the road.

Campbell was still clearly struggling with schizophrenia, but he told his sister he was content living with other men in the church-owned home next to the sanctuary.

“He was happy. I mean, to the extent that he could be,” Madena said. “He liked where he was. He said, ‘These are my people.’”

But doubts crept in about his care. Madena said staff at the church asked her to buy basic items, including food and toilet paper.

“I’m like, but my brother gets a check every month—two checks, military and Social Security,” she said.

When Madena’s daughter, Patrice, insisted on going inside the home, she said she saw a bare fridge, messy bathroom and other spartan conditions for the older men living there.

“That pastor had him sleeping on the couch,” Patrice said. “He had no room. He was in—like, his clothes were all full of urine and poop.”

Despite this, Campbell insisted on staying and Tagaloa continued to manage everything, according to Madena.

“And I wasn’t happy with how he was taken care of but, you know, that was his comfort zone,” she said. “And he didn’t want to leave.”

Soon, Madena decided to call the police.

Campbell had disappeared again. It was Dec. 28, 2017—just a few months after Madena had reunited with her brother. Now she was telling a Long Beach police detective he hadn’t been seen in three days after reportedly walking away from the Second Samoan Church.

In the affidavit, investigators wrote that Tagaloa also tried to file a missing person’s report after Madena, but the detective on the case, Greg Krabbe, was never able to get in touch with the pastor.

Krabbe, Madena says, was dogged in his search, every day calling new hospitals, convalescent homes or morgues. Campbell’s family mounted its own effort, distributing flyers and hunting down reported sightings.

During this period, authorities allege, charges kept racking up against Campbell’s bank account, including political donations, a $300 ATM withdrawal and more checks to Tagaloa’s church.

Seven months later, an email reportedly ended the search.

Campbell was at a convalescent hospital in Gardena, Tagaloa wrote to Krabbe, and when he got out, Campbell would return to live at Second Samoan Church, the affidavit recounts.

Long Beach police say Campbell arrived at the convalescent hospital just three days after Madena filed the missing person report, but it’s unclear exactly when Tagaloa knew this.

When Krabbe pressed Tagaloa, the pastor admitted he’d known for at least three months that Campbell was at the facility, the affidavit alleges. Why hadn’t he mentioned this while the family and Krabbe searched?

“We all have other things we do,” Tagaloa responded, according to the affidavit. “You could’ve kept in contact with me too.”

After Krabbe learned Tagaloa had power of attorney over Campbell, he asked Long Beach’s financial crimes detectives to investigate, and they, in turn, referred the case to the state Department of Justice.

Investigators quickly found that Campbell still owed almost $1,000 for his care at the convalescent hospital, even as Tagaloa spent his money on other purchases, the affidavit alleges.

By the time his family saw him, Campbell was in even worse shape than before, according to Madena. He previously had trouble talking, but now he was essentially nonverbal, Patrice, his niece, said.

Instead of Second Samoan, he was moved in March 2019 to an elder-care facility in Palos Verdes, where Tagaloa continued to manage his money, the affidavit says.

As long as he was taken care of, the family wasn’t concerned with Campbell’s financial arrangement with Tagaloa. “That wasn’t what we were thinking about,” Madena said.

Tagaloa reportedly mailed checks to the residential facility, which bathed and fed Campbell along with administering his medication. According to the affidavit, a worker told investigators Campbell had anger issues and could be combative and confused. He was unable to talk intelligibly, but he enjoyed listening to jazz and writing.

The worker told investigators that Tagaloa visited only a few times, according to the affidavit, at one point asking for a reduced monthly fee for Campbell’s care because his finances were low.

For the first time since he was found, his children, too, were able to see him in person.

Together in the end

Sounmi said she didn’t know the scope of the alleged abuse against her father until last week when she read through the affidavit supporting the criminal charges against Tagaloa.

All the details still aren’t publicly known. In the affidavit, investigators describe over 50 transactions they thought were suspicious, but they also seized six years of bank records that could contain more details.

The charges against Tagaloa accused him of stealing more than $100,000, but the California Attorney General’s Office declined to give a more exact figure or describe further what Tagaloa allegedly spent the money on other than to say they were “unauthorized expenses.”

Prosecutors haven’t found evidence of Tagaloa gaining guardianship over anyone other than Campbell, a spokesperson for the State Attorney General’s Office said in an email.

Sounmi said her father was clearly unable to adequately care for himself, but if his children had been in control, perhaps they could have gotten him better treatment before he ended up on a couch or in a convalescent hospital.

“There’s no reason that my father had to live like that,” she said. “We needed that pastor’s help and he neglected to contact us.”

Last year, Sounmi said she was able to fly from North Carolina to visit her father about once every month. As his health declined, she and her brother, Larry, made sure he wasn’t alone.

On a November trip, the airline lost her luggage, Sounmi wrote on Facebook, but she was in a positive mood because “Daddy waved and smiled at us when we walked in.”

Later that month, Campbell died.

During his final days, Sounmi and Larry flew out Campbell’s grandchildren. With the COVID-19 pandemic raging, they stood outside his room’s window where he could see them gathered for him.

Before they left, Sounmi said, they pushed back the windowpane just enough to reach inside and feel his hand—one last touch from the man with whom they’d lost so much time.