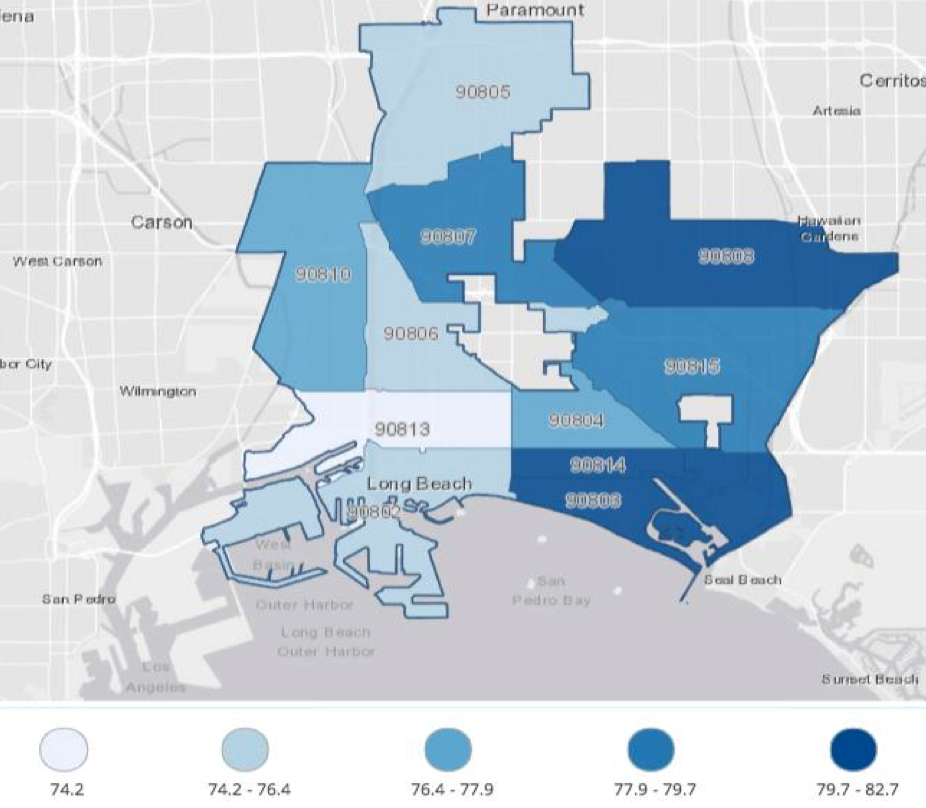

In the 90808 ZIP code in suburban East Long Beach, residents have the city’s highest life expectancy with an average of 81.2 years, and they see the lowest poverty rate at 5%.

The neighborhood also has the city’s lowest rate of coronavirus infections, with 667 cases per 100,000 residents, as of July 20.

Seven miles across town in dense Central Long Beach, residents in the 90813 ZIP code live an average of 74.2 years—the city’s lowest life expectancy—and nearly 35% live in poverty, according to a study last year by Long Beach Memorial Medical Center. The neighborhood has the city’s highest infection rate with 1,767 cases per 100,000 residents.

For many residents, Long Beach is a tale of two cities, where disparities in crime, income, education and health have existed for decades. Experts say those long-standing inequalities have now come into stark view as the coronavirus ravages vulnerable communities.

Dr. Elisa Nicholas, head of The Children’s Clinic in Long Beach, said most residents in highly infected areas work in essential jobs, which can’t be done from home and puts them at greater risk for contracting the virus through workplace interactions.

“The coronavirus pandemic has really brought to light all these inequities among people that are living in the areas where we have the highest rates,” she said. “Much of those disparities are dependent among the socioeconomic level and the social determinants of health.”

For a closer look at the disparities among neighborhoods, the Post analyzed COVID-19 infection rates in the city’s 11 ZIP codes. To better assess the coronavirus’ rate of spread in individual communities, the Post removed cases within nursing homes, which account for 17% of the city’s overall numbers.

The disparities among neighborhoods are even greater when nursing homes are removed from the statistics. For example, the 90815 ZIP code in East Long Beach as of July 20 had a rate of 1,062 cases per 100,000 residents, but nearly 200 of those cases resulted from outbreaks in two nursing homes. Without the nursing home cases, the area’s coronavirus rate is cut in half to 594 cases per 100,000 residents, giving it the lowest rate in Long Beach.

In contrast, the Post analysis showed that the high infection rates in the city’s hardest-hit ZIP codes in North and Central Long Beach remained virtually unchanged because, unlike the city’s east side, there are few nursing homes in those areas.

Nicholas, who has studied health issues such as asthma rates and other chronic health conditions in low-income communities, said economic disparities, educational barriers and environmental hazards all have played a role in how the pandemic affects different parts of Long Beach. To make an impact, she said, the city must work to reduce crowding, increase public park space and provide more economic stability.

“You can’t just address those from a medical solution,” she said. “Only 20% of a response to health problems has a medical solution.”

North Long Beach

North Long Beach’s 90805 ZIP code has the city’s largest population with more than 93,000 residents. It also has the highest overall number of coronavirus cases with 1,602 as of Wednesday.

Councilman Rex Richardson, who represents the area, said health inequities in neighborhoods like North Long Beach are not new. He said the pandemic has highlighted disparities for Black residents, who account for 12% of the city’s population but 20% of all coronavirus-related deaths.

Richardson noted that Black residents in neighborhoods with large numbers of coronavirus cases are more likely to be homeless and economically unstable.

“We have two very different realities as it relates to health,” he said. “COVID-19 is the perfect storm.”

In an effort to address the racial disparities, city leaders last month passed the Black Health Equity initiative to funnel state and local money directly into Black communities.

Before the initiative’s creation, none of the initial relief money of about $800,000 in small-business micro loans went to underserved communities in North Long Beach or the Westside, Richardson said.

“It didn’t go to the businesses in the areas that are hardest hit,” he said. “Black businesses, Latino businesses barely benefited from these loans. By the time they heard of the loan, the money was gone.”

Now, the city is placing federal relief funds into racial equity programs, like the Black Health Equity initiative, to directly benefit predominantly Black neighborhoods, Richardson said.

He said he’s hopeful the pandemic will bring more focus on racial inequality at all levels.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has shown us that we were right,” Richardson said, “and we don’t have a lot of time to turn things around. We need to adjust this with urgency and vigor.”

Downtown density

As coronavirus cases surge, the tightly-packed ZIP code of 90813, which encompass roughly three square miles just north of the Downtown core, has become an epicenter.

The ZIP code also has the city’s highest poverty rate, lowest life expectancy and highest crimes rates.

Councilwoman Mary Zendejas, whose district includes the neighborhood, said the area has many Black and Latino families with essential workers. Residents often live in multigenerational households, making it easier to spread the virus among family members.

“A lot of my constituents tell me they’re scared of the virus but they can’t stay home because they have to work to put food on the table,” she said. “Staying home is not an option for them.”

California’s Latino population has seen the highest infection rates, making up 55% of cases while accounting for just under 40% of the state’s population.

In Long Beach, the Latino infection rate is roughly the same as the population at about 40%.

Zendejas said the impact on Latinos is now a major focus for Long Beach officials as the virus quickly spreads through the community. She said the city is providing materials in Spanish and has held town hall meetings for Spanish speakers.

She said she especially wants to target older and undocumented immigrants who may be mistrustful or reluctant to talk about health issues.

“There are people that are afraid to come out and ask for help and we really need to reach out to them,” she said. “We have to be as much in their face as possible.”

Cambodians and Pacific Islanders

Suely Saro, a refugee from Cambodia who lives in the 6th District, which has some of the highest infection rates, said she’s also battling mistrust and wariness from older immigrants in Long Beach’s large Cambodian community.

“There’s a lot of misinformation circling,” she said.

Saro, who is running for the 6th District’s City Council seat in November, said she’s not surprised her neighborhood is a COVID-19 epicenter because of the many socioeconomic challenges.

“We have multiple generations of families living in apartments, so you don’t have a room to quarantine yourself,” she said. “There’s people sleeping in the living room, people in the garage, people in every space.”

The city on Thursday held its first town hall meeting for Khmer speakers. Saro said she hopes the intensified outreach effort will help to dispel misinformation about COVID-19, but wonders why the city is only now convening a town hall when the virus has been raging for months.

“Why did it have to take so long?” she said.

Concerns are also growing for Pacific Islanders, who now have the highest death rate out of any group in Los Angeles County.

Pele Ili, 26, lives in the 90804 ZIP code in Central Long Beach, which has some of the city’s higher case rates. He said he’s glad the city recently started breaking out Pacific Islanders as separate from Asians in its case numbers, considering Long Beach’s large Samoan population.

“It’s important for us to raise awareness about this in the Samoan community,” said Ili, whose parents are from American Samoa. “We’re a very close-knit community and it’s in our culture to have large family gatherings.”

Ili lives near the Traffic Circle with his parents and two younger brothers in a three-bedroom apartment. He said he contracted the virus in March and it quickly spread through his family. His mother, father and 22-year-old brother were all hospitalized at one point but have since recovered.

Ili has posted videos about his family’s experience on his YouTube channel to help raise awareness for young people and those in the Samoan community.

“People should know that no one is invincible to this disease,” he said. “It’s something that we should all take seriously.”